You might not know exactly what you will be doing a year from now, on April 8, 2024. It’s pretty hard to predict a year in advance. However, on that date, a total solar eclipse will occur in parts of Mexico, the United States and Canada — including parts of southern Ontario and Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland — a rare phenomenon.

The total solar eclipse will be visible in locations including: Niagara Falls and Hamilton, Ont.; Montréal; Fredericton, N.B.; western P.E.I.; the northern tip of Cape Breton, N.S.; and Gander, Nfld.

Cities like Toronto and Ottawa will be just beyond the path of the total solar eclipse.

While partial solar eclipses happen quite frequently, the total disappearance of the sun behind the moon only occurs when the moon is closer to our planet or the sun is at its furthest point from it. It is a question of the size of the moon compared to the sun. When the two are perfectly aligned, it creates a shadow cone that allows people on Earth who are within this narrow band to enjoy the unique spectacle of a total eclipse.

On average, this alignment only occurs once every 375 years, but it can vary. For example, the last total eclipse visible in Montréal occurred on Aug. 31, 1932. Other regions in Canada have not been as lucky. In St. John’s, Nfld., the last total eclipse was on Feb. 3, 1440, and locals will have to wait a total of 765 years for the next one, which will happen on July 17, 2205! The record belongs to Regina, Sask., which had a total eclipse in 54 BC, but will not see another one until Oct. 17, 2153 — or a total of 2207 years!

So try not to miss the total eclipse in places like Montréal in 2024. If you do, you’ll have to go to a location like Calgary for the next one, in 20 years.

Yet the phenomenon does pose significant risks to eye health. As an optometrist, I am very concerned about eye health issues. I certainly wouldn’t want anyone to go blind after watching a solar eclipse without properly protecting their eyes.

Watch it, but protect yourself

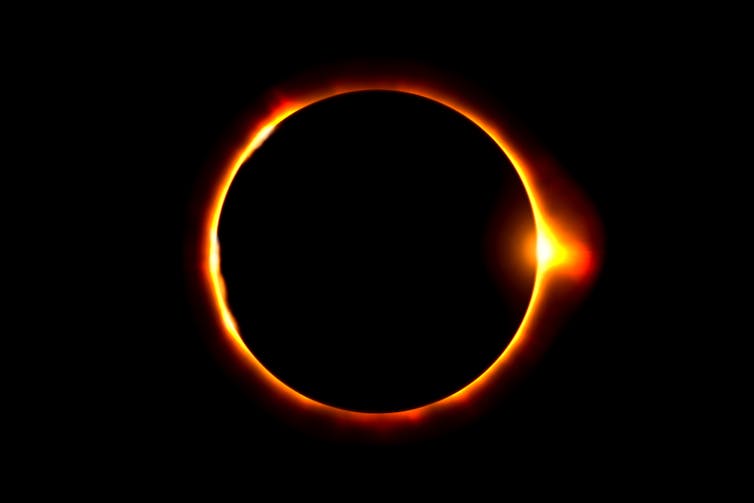

Watching a total solar eclipse is always fascinating. During the phase when the moon completely obstructs the sun, daylight is transformed into a deep twilight sky. The sun’s outer atmosphere (known as the sun’s corona) gradually appears, shining like a halo around the moon. The bright stars and planets become more visible in the sky.

In daylight, the sun usually emits visible light that is so intense we cannot look directly at it for very long. If our eye ever looks directly at the sun, we have the reflex of turning away from it immediately, after an average of only 0.25 seconds. This reflex provides natural protection for eyes against the harmful rays of the sun, some of which — notably ultraviolet and infrared radiation — are not visible.

Ultraviolet radiation (UV)

UVs accounts for seven per cent of solar radiation. They are partly absorbed by the cornea (the clear part at the front of the eye) and the crystalline lens (the natural lens inside the eye), without causing any damage, unless the exposure is too great.

In such cases, depending on the amount of UV radiation it absorbs, the cornea may develop inflammation, known as keratitis. The lens, in turn, loses its transparency — this is called a cataract. Other impacts can be expected, such as the development of small cysts (pinguecula) on the conjunctiva (white of the eye) or a membrane invading the cornea (pterygium).

Eyelids can also develop skin cancers. The upper eyelid, which is usually not exposed on the outside when our eyes are open, is particularly at risk when we lie on the beach with our eyes closed without protection. Finally, UV light predisposes us to macular degeneration, which is a damage to our best retinal cells and can result in varying degrees of vision loss.

These diseases all develop as a result of direct radiation, but can also come about when the sun’s rays are strongly reflected by surfaces such as snow (snow ophthalmia), sand or water. It is therefore recommended to wear protective eyewear that cuts out all UV rays (UV400 protection) when you plan to spend more than a few minutes in the sun. For both children and adults, the frame should wrap around the eyes, so that no rays pass through the side or top.

Infrared radiation (IR)

IRs make up the majority of the radiation emitted by the sun — 54 per cent. We feel the effects because it is thermal radiation, which is accompanied by heat.

While the cornea (burning) and lens (cataract) can also be affected by IR, it is more the retina that can suffer from inappropriate exposure to IR. Again, it is a question of intensity and duration. As with UV radiation, the more intense the radiation, the more permanent damage will occur in a short period of time.

IR damage to the retina destroys the cells that allow us to see and ultimately creates a scotoma, a permanent black spot in our field of vision. This is a cause of blindness.

Eclipse and radiation

When the Sun is only partially hidden (partial eclipse), the UV and IR radiation is as important as in full sunlight. However, because of the reduced luminosity, we no longer have the natural reflex of turning our eyes away. So it may seem more comfortable to observe the sun for several seconds or even minutes. Without protection, this type of exposure can lead to the pathologies described above and contribute to blindness if the central retina is affected. U.S. President Donald Trump was reminded of this in 2017, when he watched a partial eclipse without protection, putting his vision at risk.

During a total eclipse, however, it is possible, during the short duration of the total obstruction of the sun (one minute 37 seconds), to look at the solar corona without protection. But you must be very vigilant and remember to put protection back in place as soon as the Moon starts to move and the radiation becomes present again, even though the ambient luminosity is still reduced.

The same precautions should be taken when viewing the eclipse directly through binoculars, a telescope, a camera or other optical means. For example, do not look at your phone screen with the naked eye when trying to take pictures of the eclipse. The rays are not blocked by these instruments and can cause significant eye damage.

A question of protection

So, what kind of eye protection are we talking about exactly? Sunscreens that can be mounted in glasses or in temporary glasses, made of cardboard, but that cover the entire surface of the eye perfectly. Once again, it is important to avoid leaving a gap between the eye and the protective screen through which harmful radiation can enter. Permitted filters must meet ISO-12312-2.

Before wearing such filters, be sure to follow the instructions provided with the equipment. It is very important for parents to ensure that children wear the filters properly and do not play with them. When the observation is over, do not remove the filters while you are still looking at the sun: look away, turn your back to the sun and remove the filters. Then don’t look at the sky anymore.

If ever…

Damage to the cornea and retina can occur within hours of exposure, but not always immediately. If you have ever been inadvertently or recklessly exposed, monitor your vision in the hours after the eclipse. If you notice any blurring or changes in your vision, you should consult an optometrist or ophthalmologist as soon as possible.

Many activities will be organized for the arrival of the total eclipse. To make the most of this unique event, watch for announcements from organizations such as Space for Life, institutions such as the Université de Montréal, or your local astronomy clubs. These organizations will provide information, may provide protective glasses/filters and, most importantly, will help you to better understand the phenomenon.

See you in a year’s time! But in the meantime, whether young and old, let’s all protect our eyes properly.

Langis Michaud does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.