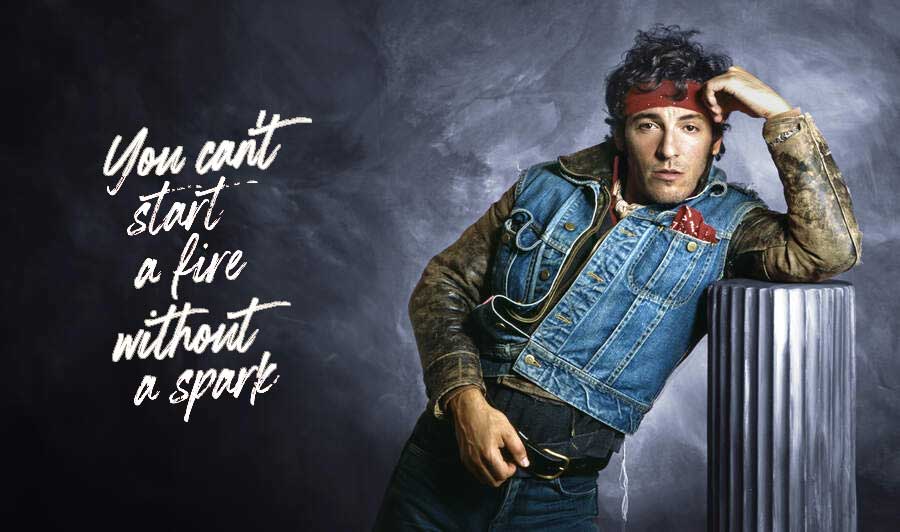

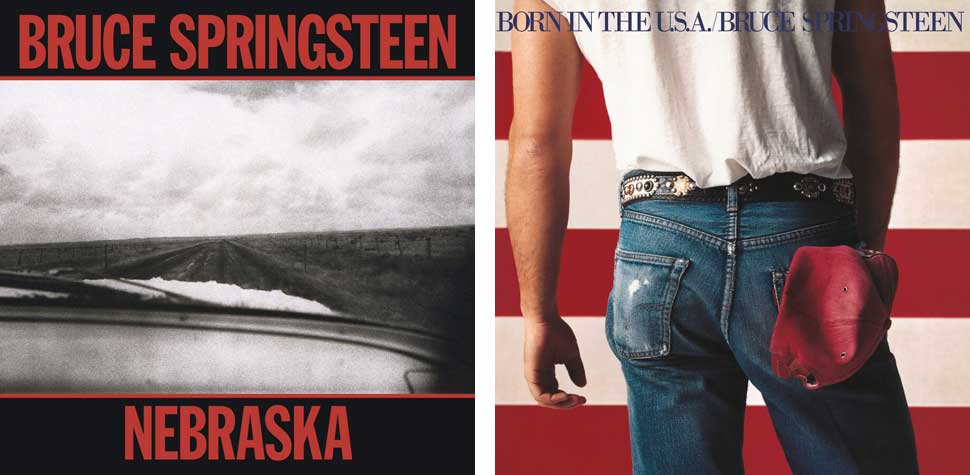

Almost as soon as Born In The U.S.A. was released, people began telling different stories about what was going on with the album’s cover. Call it one sure sign of success. In somewhat the same way that Abbey Road generated interpretations, theories and myths regarding the artwork, so too did Born In The U.S.A: he’s pissing on the flag; he’s been lifting weights and wants us to see his ass; he’s a good American boy, paying tribute to his country, ball cap in his back pocket.

However ungrounded these readings, there they were. Then US president Ronald Reagan, not one for spending great amounts of time analysing album covers or rock lyrics, preferred the last of them, and publicly voiced his kinship with the artist. Springsteen, not surprisingly, wasn’t inclined to go on that blind date.

Not all album covers have that kind of immediate impact. Most don’t. Typically, the music gives the artwork meaning over time. But there are those rare ones that hook audiences straight away, that jumpstart the experience of an album even before the music begins to do its work: The Clash’s London Calling. Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain. The Velvet Underground & Nico. Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly.

To be fair, if the creation of such album covers was a simple matter, everyone would be doing it. In his first 10 or so years on the Columbia Records roster, Springsteen showed that he took image seriously and possessed a notable intuition and sophistication regarding using visuals both to introduce an album and build an identity. When it came to cover art, he nailed it more than once. Early in his career, Springsteen figured out how to collaborate with photographers and art directors, how to style without giving the sense that anything had been styled. Most of this was done through gut instinct and self-guided study. He learned how to reject artwork and explain why he was doing so, how to connect image and music.

In a relatively brief period, he released multiple albums that had immediate-impact covers, including Born To Run and Darkness On The Edge Of Town. But Born In The U.S.A. was perhaps the most emphatic visual statement of them all. That one took you by the lapel, made sure it had your attention. You got the sense that the album was a thing of dramatic intention, like he knew exactly what he wanted to do to us and he went and did it.

Between the Annie Leibovitz photograph, with its saturated colours and aggressive cropping, and the album title itself, there was a sense that something significant, something new to the artist was inside. And as soon as you began listening to it, it was confirmed. The first song was the title track. It was a skeleton arrangement from the first verse through the first chorus, featuring Roy Bittan’s repeated synthesiser line and Max Weinberg’s massive snare drum, and it allowed the bite of Springsteen’s vocal a new kind of exposure. As an opening track, Born In The U.S.A. came on like some kind of manifesto.

The album cover was a statement, the production was a statement, the song was a statement. It wasn’t a situation that had listeners stopping after the first track. And that, of course, was the idea. But Born In The U.S.A. was not an easy birth, not, in fact, a thing of deliberate intention until the very last stages of its emergence. Springsteen’s seventh official album release was career-changing, doing its work from the moment listeners got the thing in their hands.

It was a ride you got on and stayed on. But while Michael Jackson’s Thriller, a near contemporary of Born In The U.S.A., was the result of what its producer Quincy Jones described as a kind of military strategy, a focused, deliberate response to the poor showing at the Grammys of Jackson’s previous album Off The Wall, Born In The U.S.A. was another matter entirely.

Sure, it seemed like a similar thing, as if some team was lurking in the shadows, saying: “Let’s take this motherfucker to the top.” But that’s not how it went down. It wasn’t like that in Springsteen’s world. Not then, not now. Born In The U.S.A., Springsteen told me, “was just what I had lying around".

At the heart of the Born In The U.S.A. story is the deep and, arguably, under-discussed art of ‘sequencing’, putting things in order. As one CBS executive put it: “Bruce and Jon [Landau, Springsteen’s longtime manager and co-producer at the time] have truly laboured over sequences.” But while the term is most commonly used to describe the track-by-track organisation of an album, there are other sequences that matter to Born In The U.S.A., including that of Springsteen’s album-to-album development and Born In The U.S.A.’s single-to-single release schedule. Even that cover art, so effective, needs to be understood in relation to what came before it, as a point of contrast.

The wild success of the album was due, at least in part, to a kind of mastery in all those areas of sequencing, even if that mastery didn’t always come easy, and felt, from the inside, more like stumbling. But there’s an art to the business of getting albums into the world and of building an image over time, and Springsteen showed a rare intuition and instinct in practising it. Only in some unfounded myth of authenticity – and rock’n’roll culture loves its myths – can a popular recording artist live at arm’s length from the world of commerce.

In actuality, artists can’t just make the recordings, holding their noses as they hand their work to the business people who then take those recordings to the marketplace. Artists often choose the timing, the packaging, the order in which the work is presented and which songs in a collection are emphasised. In that regard, Springsteen has a history of deep involvement, his ‘office’ typically the last stop before final decisions are locked in. Sometimes, late in the game, he’s held back brilliant music, stopped the process, believing a record’s moment has not yet arrived. This was indeed the case with much of the material that would become Born In The U.S.A.

In Springsteen’s career there have been numerous times when he’s shown remarkable intuition in plotting his own artistic trajectory, even when his moves were more instinctive than overtly tactical. His decisions, sometimes going against the grain of what his fans and even his inner circle believe to be good and right, have often been the very thing enabling the long career we witness today, with Springsteen, aged 74, moving stadium-to-stadium across Europe.

One could argue – and I would – that when he let the E Street Band go in late 1989, starting work on Human Touch and, ultimately, Lucky Town with mostly session musicians, it was the very decision that would allow the E Street Band to come together later with a new and lasting strength.

Was disbanding his group a popular decision among fans? Certainly not. And they were hard on those records. But it gave Springsteen room not just to breathe but also to try some things, walk a few avenues where he didn’t recognise the houses. And what he found there would inform his later work as both a record maker and a bandleader of, yes, the E Street Band. Short-term disruption, long term gains. If Springsteen lived by the popular vote, there may well not be an E Street Band today

While Springsteen will be remembered as an artist of many talents, songwriting, performance, and record-making most conspicuous among them, he is also a master of crafting the long career. He’s one to study in that regard. Any particular chapter in his career needs to be situated within the greater story, simply because he’s been sculpting from a larger mass than just albums and singles.

There’s no understanding Born In The U.S.A. without looking around it. What album came before? What came after? How do they relate? So the best approach to understanding Born In The U.S.A. is to begin by looking at the album it followed, Nebraska (1982), and then consider where Springsteen went after, Tunnel Of Love (1987). How did the various projects look, sound and arrive in relation to one another? With Springsteen, always go wider when you want to understand what he’s doing. That’s where you’ll find answers.

In hindsight, who could imagine Born In The U.S.A. coming immediately after The River or leading directly to Human Touch? Born In The U.S.A. had Nebraska on one side and Tunnel Of Love on the other, both records of isolation, of surprising interiority. It’s like Springsteen could only do a Born In The U.S.A. if he could live in a cave before and after he did it.

Springsteen didn’t situate himself in front of Annie Leibovitz’s camera (apparently urinating on an American flag) until he first put out what is arguably the strangest, most unexpected recording of his career, Nebraska. The black-and-white photo on that album’s cover, taken by David Michael Kennedy, shows an uncertain rural landscape, flatter than flat, seen from the front seat of an old vehicle, a human presence implied only through point of view.

That cover, too, suggests something about the music inside, although in Nebraska’s case it’s dark, violent, vulnerable, muddy, a strange mix of unnerving emotion and cold distance. The cover art is as different from that of Born In The U.S.A. as the music of the one record is from the other. It was as if the two projects came from different artists with different sets of ambitions at different times. But that wasn’t the case.

For a minute there, the album-to-album sequencing that led from The River to Nebraska to Born In The U.S.A. could have unfolded differently. As Springsteen would later recall, the greater part of Born In The U.S.A. was indeed finished when he decided to turn his attentions to preparing the Nebraska material for release.

That decision to focus on Nebraska, a project that would confuse many fans and sit in the marketplace like some uninvited stranger, was a surprise to many of those working with and around him, much like that later decision to break up the E Street Band. His team had a clear sense for the strength of the more commercial material he had ready – and all they could do was watch him set it aside. “[Nebraska] was just where he had to go,” Jon Landau told me. And months became years.

As I discovered in my interviews with Springsteen and his team, Nebraska and Born In The U.S.A. were like fraternal twins, coming into the world in the same general period while ultimately looking very different from one another. For a time there, though, they were sleeping in the same crib. But one was an outcast, the other class president.

It was only deliberate sequencing that would put distance between them, with recordings like Born In The U.S.A., Cover Me, Glory Days, and I’m On Fire shelved indefinitely so that Nebraska could come first. The separation would give listeners the sense that these two albums had little to do with one another. But while their release dates suggest a definitive birth order, with Nebraska arriving first, in 1982, Born In The U.S.A. second, in ’84, those release dates obscure more than they illuminate.

What they do reveal, however, is Springsteen’s deep sense of the order of things as he needed them to be ordered, for the purposes of a larger story and the unfolding of an artistic life. 1982 just wasn’t the right time for Born In The U.S.A. The truth is that the bulk of the material that would go into the two albums went from Springsteen’s mind to his fingers in the same general period, despite the fact that no two other releases in Springsteen’s catalogue are more different from one another. It’s a situation that speaks to the messiness behind the record-making process. Final results often tell us little of the second-guessing, pruning, backtracking, indecision and creative striving behind them.

Of course, the radical difference between Nebraska and Born In The U.S.A. is in some ways a symptom of the artist’s alienation from his own experiences at the time. What was going on that could find him in two such different places at once, not immediately knowing which of them he belonged in?

In time, Springsteen would give us answers, particularly through his memoir, Born To Run. But the fact remains, when he finally decided to focus his attention on Nebraska, he was setting aside five recordings that would become Top 10 singles and others with them. Jon Landau elaborated on this in my interviews conducted for Deliver Me From Nowhere.

“Bruce kept doing this dance between questioning and embracing the album he was making that would have Born In The U.S.A., that would have Glory Days, that would have Cover Me,” Landau said. “I’d heard [the track] Born In The U.S.A., and I felt it was some kind of hit. I didn’t know if it was a Top-40 hit, but I knew it was going to get people’s attention. Glory Days? It felt like a smash.

"So he knew, in my opinion, that on one hand he was on to something that could be really explosive and raise his profile as a mass artist. He had reservations about that. No secret. And he’d written this other collection of songs, the Nebraska material, that was very independent, certainly not geared toward mass appeal. Two extremes, same songwriter, same time. It’s like he had his Star Wars and his art movie in his hand at the same moment. And he went to Nebraska first.”

With so many decades behind us and a somewhat better understanding of Springsteen’s life in those years, however, there’s reason to re-establish the connectedness of those two releases. Most significantly, in making Nebraska Springsteen had some experience of giving his voice and his stories a new kind of exposure, like he’d walked into an open field and was alone there. And needed to be.

As a singer, there was no pushing to get up and over a band, and it secured for him and for the music what might be called more ‘literary’ space. The emotion of a lyric could be expressed in a greater number of ways when he was one-on-one with a song. The narrative had an increased emphasis. One taste of that, and a songwriter might want more. And Springsteen did. The main point here is this: the securing of that expanded territory for voice and story didn’t stop with Nebraska.

Listening back to Born In The U.S.A. now, one can hear Springsteen claiming it there too, if using production strategies very different from those associated with Nebraska. The synthesiser on My Hometown, I’m On Fire and Dancing In The Dark provides a full sound that nonetheless leaves important space for the nuance of the voice, its grain and emotion.

The reduction of drum fills in tracks like Working On The Highway and Dancing In The Dark and the near absence of guitar solos across the entire record also support that shift in priorities. The effect favours the songwriter, and it’s an approach that would mark Springsteen’s recorded work moving forward. In some sense, Nebraska, which got the songwriter alone, was a gateway to Born In The U.S.A., not a deviation from it.

Some 40 years after recording the Nebraska tracks and select Born In The U.S.A. demos in his bedroom at a Colts Neck, New Jersey rental house, Springsteen called me from that same space.

“It’s Bruce,” he said, “I’m standing in the very room where I made Nebraska. I haven’t been here in almost forty years.”

Only a few days before that, he had read a late-stage draft of my Nebraska book. His encouraging and kind response, sent by email, included an offer to help me in whatever way he could. I wrote back, telling him I couldn’t find the house where he made the album and was hoping to visit it as a last stop in my project/pilgrimage.

After Springsteen cleared it with the landlord, the very same gentleman who rented the house to him in 1981, we went out there together. The house no longer looks like it did in 1981, when Springsteen moved in and eventually started recording songs to a four-track recorder that used cassette tapes. A second storey has been added, the footprint extended. But, oddly enough, the bedroom where Nebraska and chunks of Born In The U.S.A. were put down remains largely intact, right down to the orange shag carpets that Springsteen had described to me. It’s almost a time capsule. After writing about the album for a few years, thinking about this artist and where he was at the time in his mind and in his craft, there I was in the room itself, with the man.

No one would watch Lifestyles Of The Rich And Famous to see a place resembling the one Bruce Springsteen moved into at the end of the tour supporting The River. Even with the additional work it’s a humble spot, located at the end of a cul de sac, a small ranch house facing a reservoir. The River was Springsteen’s first No.1 album, included his first Top 10 single, and resulted in his biggest tour to date in both the States and Europe. At the end of it, he bought his first new car. And then the lights dimmed, the pavement ended, and it was dirt roads for the next long stretch. A period of significant isolation began.

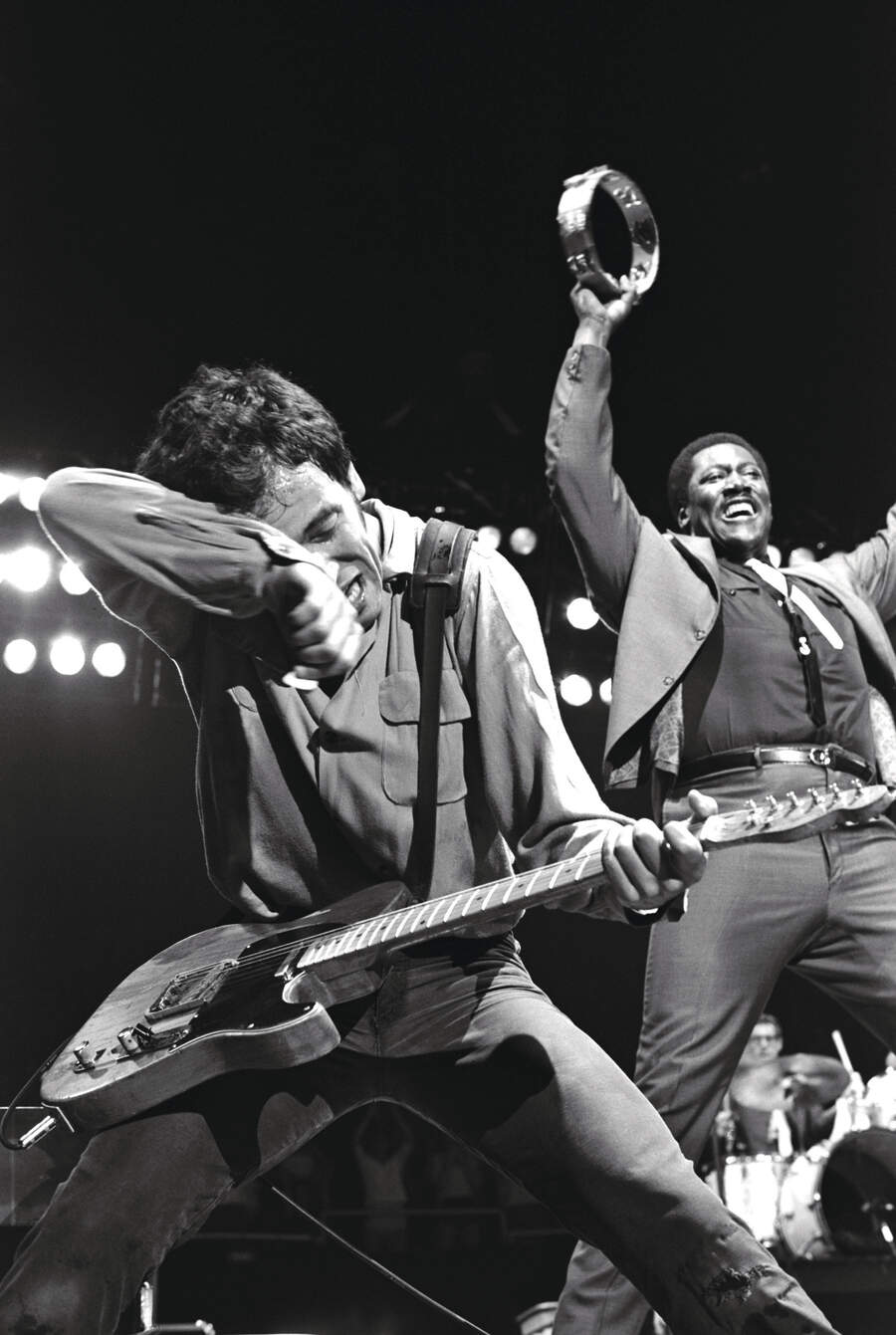

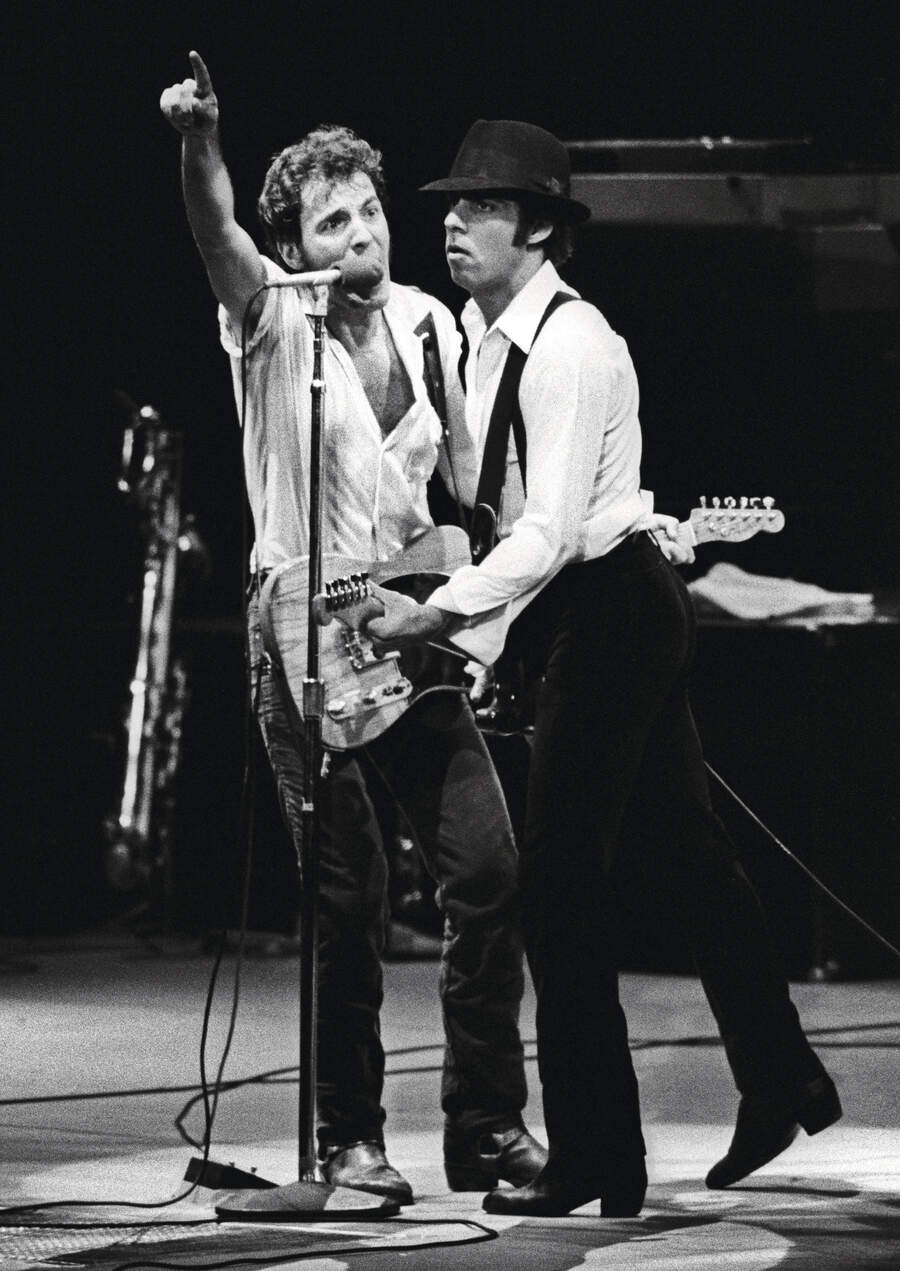

The River is a recording Springsteen describes as an effort to get the sound and experience of the E Street Band’s live show on record. In the middle of recording it, the No Nukes performances were a celebration of what that band could do. Many of the No Nukes acts stood relatively still on the stage, holding acoustic guitars, focused more on vocal harmonies than on anything like stage choreography. But the E Street Band had a show. Against the backdrop of a laid-back bill, Springsteen’s act turned Madison Square Garden into an experience James Brown might have recognised as entertainment.

Springsteen was already known as a remarkable showman, but the later shows supporting The River were going to emphasise what the No Nukes performances had made clear: this band is here to remind you what live rock’n’roll can be at its very best.

The two records that would follow The River, however, were in some way a response to what came of all that, because Springsteen was facing what one might call ‘the conundrum of multiple gifts’. When his abilities as a showman – the stamina, the audience engagement, the band leadership, the theatre – got a lot of attention, there was less talk about the songwriting. But it could and probably should be argued that Springsteen became Springsteen in the light of his songwriting more than due to any other among his gifts.

Coming off the shows supporting The River, which built on the already robust legend of Springsteen’s live show, his roadie, Mike Batlan, picked up a TEAC 144 four-track tape recorder and set it up in his boss’s bedroom. With that, Springsteen would have the capacity to do basic multi-track recording by himself. He could hear what he sounded like when no one else was around. The only thing you could fit in the bedroom was a songwriter. It was abrupt, dramatic, crucial.

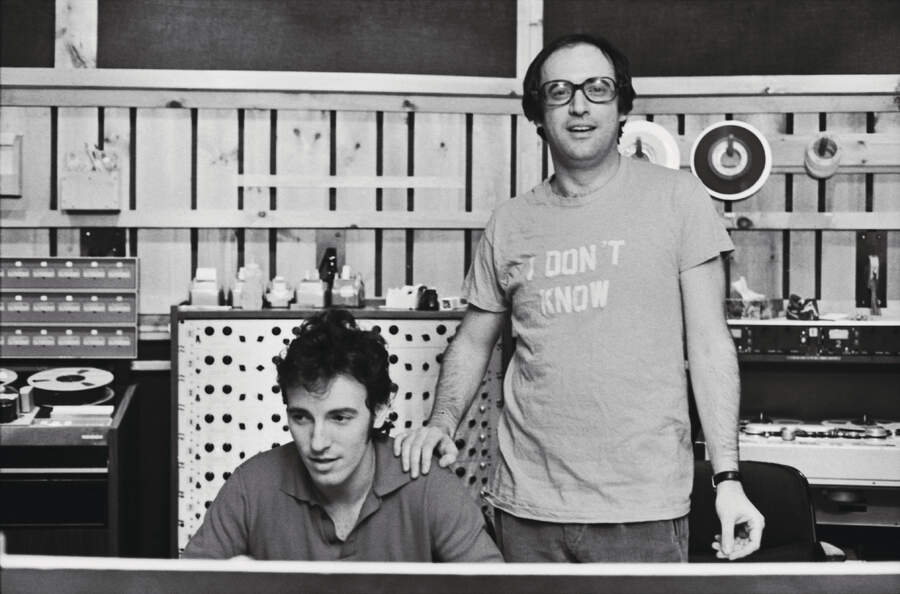

Mike Batlan ran the TEAC 144, but it was the first time he’d recorded anything. For Springsteen, that made Batlan just the right guy for the job. “I didn’t want a producer there, didn’t want anyone who would pass judgement on the work,” Springsteen told me. Indeed, Nebraska is the only Springsteen record that has no production credit, and remains the only official release that Springsteen made not knowing he was making an official release. The recordings were created as demos, intended to be used as sketches. And in some cases they were.

The songs Born In The U.S.A. and Downbound Train were among those bedroom demos re-recorded as band tracks for Born In The U.S.A. Child Bride would include elements that became Working On The Highway. Pink Cadillac would be the B-side of the Dancing In The Dark single. The overlap between Springsteen’s sixth and seventh releases is considerable, with Cover Me, I’m On Fire, Darlington County and Glory Days also coming out of sessions in that same general period.

For a minute, Springsteen was even considering a double album that would keep the fraternal twins very much together. While he didn’t linger on the idea of releasing a double album, likely because he’d already been on that particular adventure with The River, he told me he wishes he’d left the bedroom version of Born In The U.S.A. on Nebraska, if only to show the connectedness of the two projects. “It would have made perfect sense there,” he said. But he didn’t, and so any obvious cord between the two was all but cut.

Once Nebraska was released in September of 1982, the two thirds of Born In The U.S.A. that Springsteen had set aside didn’t simply come out of storage. The tracks languished, their future uncertain. As Springsteen detailed in his memoir Born To Run, it was on the heels of Nebraska’s completion that a depressive episode, a breakdown, led him to a necessary investigation of his own mental health and of his family history as it was colouring his adult life. On a road trip to Los Angeles, about to move into the first home he’d ever purchased, something gave way. It opened a gap between Nebraska and whatever would come next.

The candour with which Springsteen writes of this event and its aftermath gives his memoir its spine and emotional resonance. When he eventually got to work promoting Born In The U.S.A., fans and critics would note his physical appearance, seeing the conspicuous effects of weight training, but his memoir makes it clear that the far more significant change came in the form of a commitment to therapy in the wake of that breakdown. Call it the inside job. Personal trainers can’t get there. It was, in his words, the beginning of “one of the biggest adventures of my life.”

His focus in that moment was certainly not on the tracks sitting on the shelf, the ones that would ultimately become his biggest album ever. What he did was write and record still more material, a pile growing. Resituated in Los Angeles, somewhat lost in the in-between, Springsteen set up a more advanced studio above the garage of his new home. He wouldn’t be recording to cassettes, nor would anyone set up gear in his bedroom. If some aspect of a recording was working, the quality was such that it could easily be transferred to a commercial studio or used as it was.

For all the glory of Nebraska, that project, technologically, would remain in the ‘never again’ category. His production team and crew were there to help usher Springsteen into the next phase of his recording life, which would mean having professional-grade studios at almost every home he lived in from that time forward. Mike Batlan and engineer Toby Scott both played roles in setting up and running the Hollywood garage studio, but Batlan’s remained crucial and much as it was for the Nebraska sessions: to facilitate, not judge. Two guys, alone in a room. If there was a producer, it was, once again, Springsteen. Tracks including Richfield Whistle, The Klansmen, Johnny Bye Bye, Sugarland and a cover of Elvis Presley’s Follow That Dream are among more than a dozen recordings from this period.

As a recording emblematic of that time, County Fair, later a bonus track on The Essential Bruce Springsteen, has an elegance and restraint to it. A drum machine keeps the recording in a strict tempo, on the grid. The guitars sit in an atmospheric musical setting, no crunch. The song’s narrative, ultimately picturesque, would never fit among the dark tales of Nebraska. But like other material written and recorded in that period, it was not a blind alley. The space given to the songwriter was as generous as on Nebraska, however much more ‘produced’ the sound was. Springsteen was on his way towards Born In The U.S.A. But getting there would never be a simple matter of backtracking, of returning to fetch what had been left on the shelf. At this point, it was all forward motion, if into the unknown.

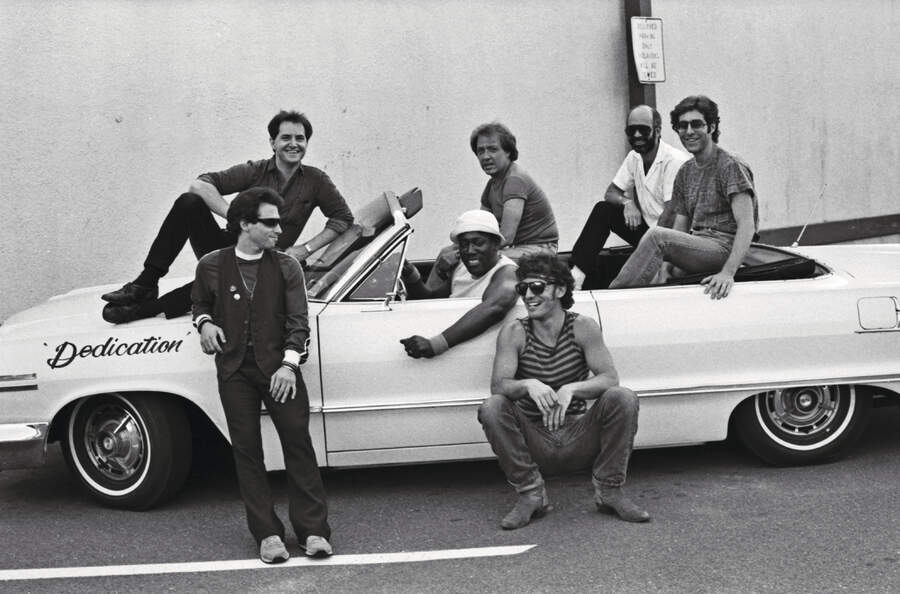

For an artist known as a great bandleader, with on-stage foils as good as Clarence Clemons and Steven Van Zandt and a posse of musicians locked in to his movements through sight and sound, Springsteen knew well that his ensemble was integral to his identity as an artist. Part of the audience experience hinged on the fact that the E Street Band members weren’t just sidemen – they were friends, with history, a gang. It was a real band. You could see it in their faces.

Because of all that, no one was thinking that Nebraska or the Hollywood solo recordings meant the band was out of a gig, Springsteen included. But, yes, there were real questions about how long they’d have to wait for the bandleader to get back to the business that included them, even if instinctively they knew it would happen in time. Among those band members, Steven Van Zandt had a somewhat elevated role. He had the longest history with Springsteen, even if he wasn’t officially in the band until the Born To Run-era performances.

By 1978’s Darkness On The Edge Of Town, Van Zandt alone was credited as an assistant producer, by 1980’s The River a producer. In the months after completing road work for The River, as Springsteen settled into life in Colts Neck, Van Zandt was getting busy. He signed a solo recording deal and went almost directly into the studio.

In February 1982, he and Springsteen worked together on a second album by Gary U.S. Bonds, On The Line. The two acted as producers, with the bulk of the material written by Springsteen. The E Street Band were playing on the record, but there was no question as to who among their numbers was out front on that one. It was the two longtime friends. But in the upcoming year, when Van Zandt went to Springsteen seeking what the bandleader later described as “a fuller role” in the band moving forward, it was a discussion that didn’t go where either man wanted it to. Van Zandt was already a producer. What could a “fuller role” mean?

If anything marked the final stages of making Born In The U.S.A., it wasn’t that the work moved studios from the Power Station to the Hit Factory, it was Van Zandt’s absence when they got there. Van Zandt would end up having a producer credit on the album, even if his input in the last stages of making Born In The U.S.A. would be less direct. By the time the record was released, his time in the E Street Band would be over. By some accounts, Springsteen found out that his guitar player’s departure was official when watching MTV news. The impact of all that on Springsteen would be difficult to measure, but no doubt his band took its biggest hit to date in losing Van Zandt.

The group had crystallised after Born To Run’s release, putting a decade in with the same players backing Springsteen. But from day one this was Springsteen’s record deal and his show. It wasn’t a Mick and Keith thing and never had been.

Springsteen has suggested that a few key songs that came late, Bobby Jean and No Surrender, related in some way to his feelings about Van Zandt’s departure. But the mood of them is hardly one of bitterness. If anything, there’s a warmth to the sense of loss that underpins the songs. In that way, they also stand out as being different from anything on Nebraska. The voice we hear sounds like that of a man at peace with things that are gone. As a response, however, it wasn’t instantaneous.

Those two songs and Dancing In The Dark came after some months of what Springsteen describes as “writer’s block”. It may be that the fissure in his band was among the things that arrested his mind. But when the log jam broke and the new material was added to the pile Springsteen had amassed, he was looking at more than 50 songs. By some estimates the number was closer to 70.

At that point, co-producers Springsteen, Jon Landau and Chuck Plotkin were in the position of having to narrow an enormous amount of material down to one album. Only then did Springsteen, with the input of the other producers, really return to the earlier material recorded before Nebraska’s release.

There’s no way to make vast generalisations about the songwriting process – it changes from writer to writer – but one can safely say that many songwriters are often unsure what they’ve got just after a song’s been written. Some look past their best work or overvalue lesser efforts. Writers have to go so far inside to find a song, they often lose the more objective perspective on what they’ve created. In many cases, a crucial part of the songwriting process involves doing, well, nothing. Time and distance, the shifting of context, allows a kind of de-familiarisation. Take six months, a year, listen again, and the writer can sometimes hear what they couldn’t before. Then the song is done.

And so Springsteen went back to tracks recorded much earlier, hearing them as he hadn’t before. Springsteen’s path from Nebraska to the Hollywood recordings to, finally, the completion of Born In The U.S.A. involved the less visible part of the songwriting process, that doing nothing part. And only then did recordings he had “lying around” begin to resonate differently for him, no doubt with the encouraging voices of Landau and Plotkin ringing in his ears. Songs recorded many months before began to sound different to the songwriter who had undergone dramatic changes in his personal life and work life. Time and altered circumstances affect the ear.

Then Springsteen got to the task of finding the album that would come next, Born In The U.S.A. The earlier recordings – Glory Days, I’m On Fire, Cover Me, Born In The U.S.A. – had what he now saw as “a naturalism and aliveness that couldn’t be argued with”. He was hearing them as he hadn’t before. But still, the pile of recordings was massive, all that material from the Nebraska period, from the Hollywood house, and from his return to New York. From it all, Springsteen and his team would take many weeks creating various running orders before settling on what we know as the Born In The U.S.A. album. But the governing quality of the tracks that Springsteen finally approved was still one of space, space for the voice, for the lyric, for the emotion and story, space for the man who came out of Nebraska looking for something more in his life.

Springsteen had a kind of reactive experience after the tour supporting The River, when he sat in his bedroom, recording alone, not having to force his voice over anything or anyone, because in that bedroom the band only had one member. He’d never done multi-track recording of an album’s worth of songs with no one else playing along or weighing in. So he let his voice drop down into the stillness and space, allowed the words to take over the wide middle of the music’s territory.

For a songwriter coming out of a run of albums that included The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle, Born To Run, Darkness On The Edge Of Town and The River, it was so much pasture, a place where he could see all around him, and because of this he could begin to imagine who else he might become. When The E Street Band recorded Born In The U.S.A. with the elemental power of its arrangement, Springsteen was under the sway of that bedroom experience.

It showed. Gutting the space gave the recording its power, the songwriter a remarkable clearing. Whether Springsteen’s recollection, Jon Landau’s, Toby Scott’s or anyone else’s who was in the room when recording Born In The U.S.A. at the Power Station, the story is one of excitement. They knew they had something on tape that mattered. “Lightning in a bottle,” Springsteen told me. It left the demo behind. It was a shout when compared to Nebraska’s whispers and haunted talk. It was all the same, however, in the way they made room for the songwriter. They stumbled into a kind of rock’n’roll minimalism that signalled a shift.

The Hollywood garage recordings further illustrate that Springsteen’s Nebraska-era bedroom experience would remain with him – again, not that everything was going to be done in an almost folk style, only that productions would be pared back, even the up-tempo rock’n’roll. Born In The U.S.A. illustrated the point.

Dancing In The Dark, the result of Jon Landau’s final push for a single, a song Springsteen wrote only after telling Landau that if Landau wanted one more, Landau should write it himself, exemplifies the high point of a production philosophy that ultimately guided the Born In The U.S.A. sessions and informed the final song selection. The synthesiser played a key role, drum fills were absent, and guitar was kept to a minimum, no solos. The voice, the lyric, everything was built around that. The spaces of production were cleared out, the density reduced.

Viewed in this way, Dancing In The Dark and State Trooper were actually a part of the same movement toward Springsteen’s next phase of record-making. Phil Spector’s production would no longer be the touchstone for the records, even when Springsteen’s live shows would continue to show that influence. Look beneath the shine and Born In The U.S.A. was as fiery and as bleak as Nebraska. Dancing In The Dark, for all its sonic joy, underscored Springsteen’s own self-loathing. ‘Man, I’m just tired and bored with myself,’ he sang.

Roy Bittan has recalled the band’s reaction to his bringing a Yamaha synth to the early Born In The U.S.A. sessions, saying there was “a reactionary effect of seeing one of those things in the flesh”. With the rise of British synth-pop sound, associated with groups including Spandau Ballet, Pet Shop Boys and Human League, there were acts willing to declare the machines associated with synth-pop forbidden, including acts who looked to Springsteen as a kind of beacon. It wasn’t a sound associated with the kind of rock’n’roll with which Springsteen was associated. But he wasn’t going to declare off limits something that might help him find the space he wanted for his songs as a writer, that more literary space.

As a record maker, Springsteen had made his way acting on a mix of intuition and reflection. He went into a kind of bubble, the terms of his search largely self-defined. Drummer Max Weinberg recalled to me an early conversation with Springsteen that took place not long after Weinberg’s entrance into the E Street world, in which Springsteen purportedly said: “We’re not in the music business, we’re in the Bruce Springsteen business.”

It’s a statement that demands interpretation. Taken the wrong way, it’s hubris. But as Weinberg made very clear, Springsteen was telling him not to be distracted by what was going on around the band. One could say it meant just follow the songs, not the fashions. Nebraska, wildly and beautifully out of step with its moment, exemplified the philosophy. But so too did Born In The U.S.A.’s use of synthesisers and approach to drums (whether in reducing fills, or gating the snare to be able to give it more space in a final mix).

If selecting an album’s worth of material from a vast pile of recordings proved a challenge, handing that material over to Bob Clearmountain for mixing may have been the easiest, most joyful part of Born In The U.S.A.’s long years of creation. Clearmountain was and is recognised as a master of sonic space. Whether with his Roxy Music mixes, Rolling Stones projects or his production and mixing with Bryan Adams, in 1984 Clearmountain was the perfect collaborator for the turn that came with Nebraska and brought Springsteen to Born In The U.S.A. From that point forward, he would be a name associated with Bruce Springsteen.

When it was time to sequence Born In The U.S.A., that song made sense as the opener, a declaration. The second song in the sequence, Cover Me, was the first to be recorded for the blockbuster album. But while Born In The U.S.A. was a significant departure, Cover Me had the effect of saying: “We’re still here, don’t worry.” If any track on Born In The U.S.A. could have come from Darkness On The Edge of Town, it’s Cover Me. There’s more lead guitar on it than anywhere else in the collection. Had Dancing In The Dark been in the second spot, the message would have been very different Instead, Dancing In The Dark was second to last in the sequence, almost buried.

Part of the brilliance of presenting Born In The U.S.A. came in how Springsteen and his production seemed to know which moves might be jarring for a devoted fan base. It meant knowing that the ‘devoted’ took in Springsteen as an album artist, because that’s what he’d always been for them. Born In The U.S.A. was sequenced for those fans. But when it came to singles, he and his team could make some different moves, knowing that newcomers would likely be coming to the party because of what they heard on the radio.

For that reason, Dancing In The Dark made perfect sense as a first single, even if it didn’t make sense being too early in the album’s sequence. And for anyone struggling with the new sounds of Dancing In The Dark, the second single was Cover Me, which had the same effect with the sequence of singles that it did in the album’s running order: we’re still here, as you remember us.

Born In The U.S.A. might have been a collection of what Springsteen had “lying around”, but its brilliance came in the sequencing of things. New listeners could get on board, old ones had an opportunity to know a favourite artist in new ways. The album felt like a statement, shot through with a kind of artistic confidence rare in entertainment and life. Springsteen went from Nebraska, raw and complicated, to a smash album with seven singles, and they both felt like they came from the same man. It made you want to watch him even closer than you had been, just to see what he’d do next.

The 40th Anniversary Edition of Born In The U.S.A. is out now via Sony.