Joseph Burgos was looking forward to his newfound freedom. He planned to write books, do some electrical work and help other ex-offenders.

Alton Mills was hoping to see his daughter walk across a stage with her nursing degree after he got out of prison.

They and a third Illinois man, Julian Wyre, are among more than 1,900 federal inmates who were freed when then-President Barack Obama granted them executive clemency — 13 times more than any other president had ever done.

Now, Burgos, Mills and Wyre — convicted drug dealers — are all back in jail.

Burgos, who pleaded guilty in September to a drug charge, is awaiting sentencing for smuggling oxycodone pills laced with fentanyl.

Wyre was convicted this past week of selling crack cocaine near Rockford.

And Mills is awaiting trial for murder in the fatal shooting of a woman in May in what the police say was a suburban road-rage incident.

Across the country, thousands of federal inmates have gotten their sentences cut short under Obama’s 2014-2017 clemency initiative and the federal First Step Act, signed by President Donald Trump in 2019, allowing convicted prisoners to petition for lower sentences in certain circumstances.

The push for more early releases came as a repudiation of draconian prison sentences created during the federal government’s “War on Drugs” that began decades ago.

Challenges of life outside prison

For ex-offenders, life on the outside can be daunting.

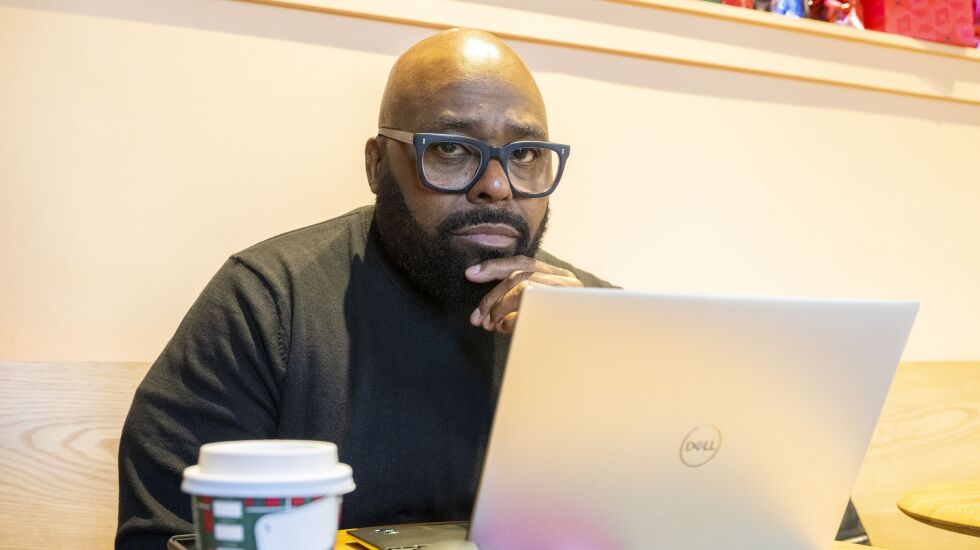

Jesse Webster is a success story. Webster — who was the subject of a series of stories by Chicago Sun-Times columnist Mary Mitchell in early 2017 — landed a job with Catholic Charities of Chicago after Obama commuted his sentence for dealing cocaine.

Still, it’s a thin line between redemption and recidivism, he says.

“I had a life sentence, which was really a death sentence,” Webster says. “Obama let me out. But Obama didn’t create anything further than that. You really had to fend for yourself.”

He says the arrests of Burgos, Wyre and Mills show that society needs to do more to help ex-offenders.

He says he doesn’t know Burgos or Wyre but briefly lived with Mills at a halfway house after they got out of federal prison in 2016.

“I thought he was doing great,” Webster says. “I really did. And so, when I heard that he got arrested again, I was, like, ‘Wow.’ ”

He notes that Burgos, Wyre and Mills represent fewer than 10% of the more than 30 people whose federal prison sentences in northern Illinois were reduced or wiped away by Obama. Most were convicted of drug crimes.

“Those guys needed more attention, needed more support, and it wasn’t there for them,” Webster says.

He credits his attorney Jessica Ring Amunson, a partner in the law firm Jenner & Block, for getting him an interview with John Ryan, then the chief of staff for Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Chicago. On the spot, Ryan offered Webster a job answering a helpline for homeless people. He’d been out of prison for only a month then.

Now, Webster runs his own businesses, doing “life coaching” and snow removal.

Despite the help he got, Webster says rejoining society after getting out of prison was tough. He remembers being puzzled while setting up a bank account when a teller asked for his PIN.

And, he says, he never would have gotten the Catholic Charities job if he didn’t know how to type. Luckily, he says he learned in prison, where inmates would compete with each other to see who typed the fastest. As a result, he says, he types 70 words a minute.

When he got out, old acquaintances he knew from being part of the criminal world sidled up to him with offers to make money illegally, but he says he refused.

He says he earned respect on the street because he’d refused to make a deal with prosecutors to cooperate against imprisoned Gangster Disciples leader Larry Hoover. Still, he says some people didn’t understand why he wouldn’t go back to selling drugs, which, in 1995, had landed him a mandatory life prison sentence that even U.S. District Judge James Zagel had said he had to give him but was “too high.”

“Now, they kind of frown on me,” Webster says of his former colleagues from the streets. “I’m doing my own thing now.”

Freed by Obama, then busted again

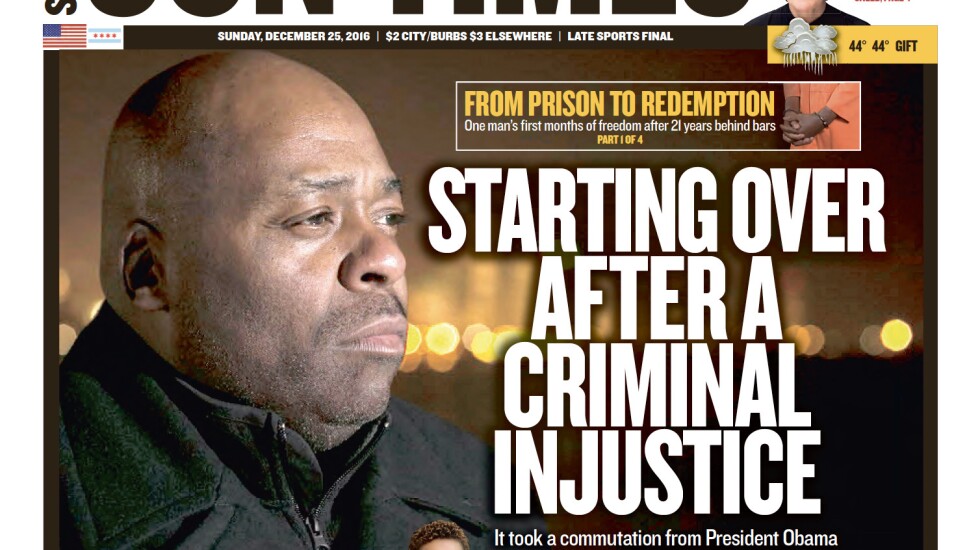

Webster, Burgos and Mills all attracted national attention after they got their clemency letters from the Obama administration.

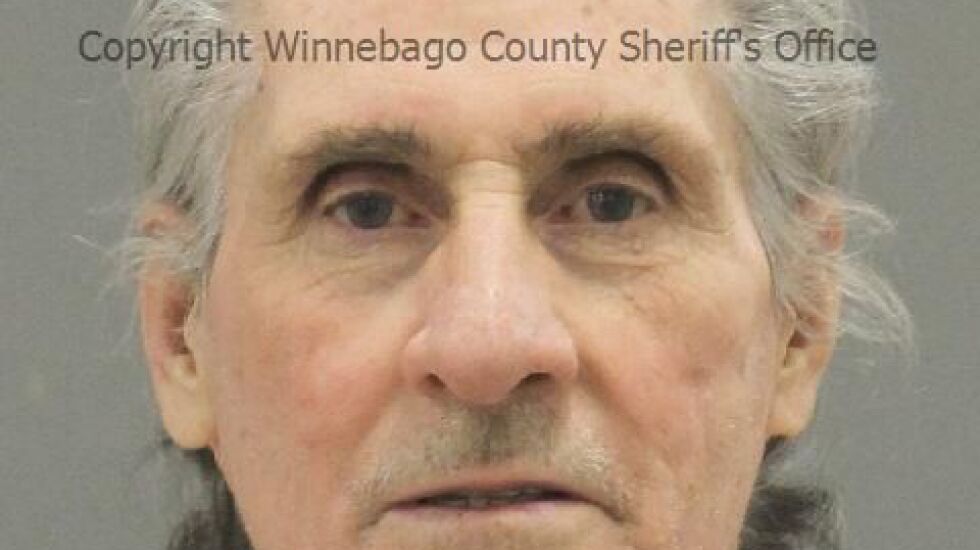

Burgos, 74, was featured in a 2016 Washington Post story headlined “One year out” that included vignettes about ex-offenders who benefited from Obama’s clemency initiative.

“I’m one of the fortunate ones, believe me,” Burgos was quoted as saying.

He called his early release from his 30-year drug sentence “beautiful” but said he wasn’t ready — he didn’t know how to use a cellphone — and said life was “really tough” for some other ex-offenders from Chicago. Burgos said he was writing a “trilogy” of books and had moved in with a girlfriend.

Then, in 2018, Burgos became a suspect in a drug-trafficking investigation. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration wiretapped his phone.

On April 13, 2019, his phone pinged in Midland, Texas. DEA agents saw he was heading to Chicago and stopped him at the Greyhound bus station. In his backpack, investigators said they found 1,983 oxycodone pills containing 212 grams of fentanyl.

Burgos had two prior federal drug convictions, including one in the early 1990s that resulted in the 360-month prison term Obama commuted in 2015.

Burgos, who was charged in 2020 with distribution of a controlled substance, is being held at the Winnebago County Jail in Rockford and couldn’t be reached. His lawyer didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“People get enticed by various things,” says Joseph Lopez, his former lawyer. “And, quite frankly, some people just can’t say no. I mean, I don’t know what else to tell you. That’s the bottom line. They can’t say no.

“I felt really bad for the guy because of his age,” Lopez says.

Though Burgos was arrested in 2019, the DEA let him remain free. He wasn’t jailed until he was indicted the following year.

At a detention hearing in 2020, Lopez asked the judge to free Burgos until trial because of the risk of getting COVID-19 in jail. Also, because he was in his 70s, he didn’t pose a risk of violence to the community, according to Lopez.

“If I contract this virus while incarcerated here, I could very well die,” Burgos told the judge. “It can kill me. And I don’t want to die while in custody, your honor.”

Prosecutors argued for Burgos to remain behind bars.

“He insists on trafficking narcotics, and, in this case, a very lethal narcotic that has resulted in many overdoses,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Kalia Coleman said at the hearing.

U.S. District Judge Young Kim criticized the DEA’s decision to “catch and release” Burgos in 2019 but decided to hold him in jail until trial, saying he posed a risk of fleeing.

Burgos, who pleaded guilty in his latest case, is scheduled to be sentenced Jan. 8. He faces, under federal sentencing guidelines, a maximum prison term of a little over five years, according to court records.

‘Casualty’ in War on Drugs back in jail

Mills, 54, who was serving a life term for cocaine-trafficking, became a standard-bearer for the movement to release prisoners who’d been given long sentences for drug-dealing.

“I hung out with a bunch of goldfishes that was dealing with some sharks, and the sharks caught the goldfishes up, and we were the ones that ended up going to prison,” Mills said in an interview on MSNBC’s “PoliticsNation with Al Sharpton.”

After Mills was released in 2016, Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Illinois, called him a “neglected casualty” in the War on Drugs.

In 2017, Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law said Mills got a job washing buses overnight in the CTA’s “Second Chance” program, hoping to become a certified diesel mechanic for the transit agency.

The law school announcement also quoted U.S. District Judge Marvin Aspen as saying he regretted that federal sentencing guidelines in 1993 required him to give Mills life without parole. Aspen said he hoped Mills would become “a role model for a lot of people who have come out of the penitentiary with the good attitude that he has.”

In 2018, on Twitter, Durbin pointed to Mills in supporting the First Step Act. That law, which took effect in 2019, allows people convicted of crack cocaine offenses before 2010 to ask to have their prison terms reduced because they would have been lower under current drug laws. According to the Justice Department, more than 30,000 inmates have been released early under the First Step Act.

Today, though, Mills is being held at the Cook County Jail, where he is awaiting trial on a murder charge. According to the Illinois State Police, Mills, living in Evergreen Park, got involved in a road-rage incident on the Interstate 57 northbound on-ramp in Posen around 3:15 a.m. on May 14. He is accused of firing into a car and striking a passenger, Linda Chattman, in the head, killing her.

At a detention hearing Wednesday, a judge denied Mills’ request to be released until his trial, noting that police said he was “angry that the victim cut him off” and fired three times into the car.

Freed, now accused of selling drugs to an informant

Wyre, a 46-year-old father of eight from Chicago, was convicted in 2008 of dealing crack cocaine and got 17 years in prison. Granted clemency by Obama in 2016, Wyre was freed the next year.

In 2019, Wyre began transporting about an ounce of cocaine at a time from Chicago to Sterling and Rock Falls, west of Rockford, where he’d get someone to cook the powder into crack, federal prosecutors say.

In 2020, Wyre was charged with selling crack to an informant. A jury found him guilty Thursday after a four-day trial.

His lawyer didn’t respond to a message seeking comment.

READ MORE ABOUT JESSE WEBSTER