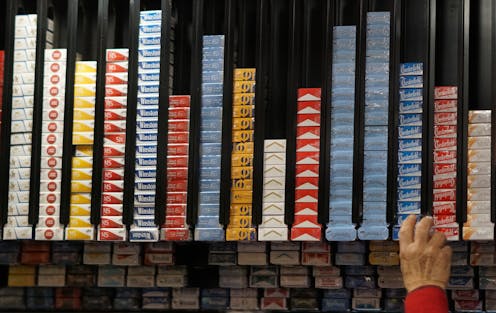

New Zealand’s smokefree law, which came into effect in January, introduces several world-first endgame measures, including removing most nicotine from smoked products, disallowing product sales to anyone born on or after January 1 2009, and a major reduction in the number of tobacco retail outlets nationwide (from about 6000 to 600).

Several studies reporting associations between greater retailer density and higher tobacco use among both adults and adolescents support this measure.

As researchers working on these issues, we were keen to know how people who smoke perceived the retail reduction measure, and how they would respond and adapt once it was implemented.

Our open-access research unearthed new insights into the potential effects fewer outlets would have on people who smoke. We were particularly interested in speaking with Māori, who bear a disproportionate burden of harm from smoking.

We interviewed 24 adult participants from Dunedin (Otepoti) and Hamilton (Kirikiriroa). We used web-based, interactive maps to illustrate the potentially large drop in retailers in these locations, compared with the current number of outlets. For Dunedin, the number of outlets in our scenario dropped from around 80 to just 3.

Impacts on daily life, wellbeing and equity

Although many expected to be able to purchase tobacco during regular shopping trips, people who did not live near a designated retailer felt the changes would disrupt their lives. They raised concerns about fuel costs, travel difficulties and risk of increased judgement.

While some expected to budget more carefully in response to the changes, others anticipated purchasing tobacco in bulk (buying a week’s supply at once) in the short term, if they could afford it. Some worried that having extra tobacco on hand could increase smoking.

As discussions evolved, many participants thought they would reduce their smoking, or quit, as access became less convenient. They anticipated better health and felt becoming smokefree would foster their physical and mental wellbeing. As one explained:

It would be a really good way for me to cut down. I’m over it … Why do I put something into my body that’s harming me? Self-harm, isn’t it?

Nonetheless, others were adamant their smoking would not change, either because they thought addiction ruled this out or because they resisted change imposed by others.

Most thought the measure would help people planning to quit and those who had recently given up smoking, as it would make tobacco less ubiquitous. They also expected reduced availability to prevent youth uptake, an outcome they strongly supported.

Participants anticipated youth would experience a “healthier, better world” where tobacco no longer threatened their wellbeing, independence and resilience.

Yet many remained concerned about people who had smoked longer-term and felt they would struggle to quit and could perhaps sacrifice necessities (food and power) to continue smoking. One said:

The younger generation … target them, that’s great, but people who have been smoking their entire lives … I think it’s extremely unfair for them.

A large majority believed the changes would burden people experiencing material hardship and mental ill health. They thought these people would experience reduced physical, mental and whānau wellbeing. Participants strongly endorsed greater community-level support, which they thought could help people managing difficult life circumstances.

Taking a wider approach

Participants’ contributions illustrate the complex and contradictory responses smokefree policies elicit. While they supported quitting (many participants hoped to eventually become smokefree) and preventing youth uptake, their concerns illustrate another, less comfortable perspective which sees the new measures as a potential threat to those who are vulnerable and addicted.

Our findings highlight the importance of community mobilisation, enhanced cessation support and strong Māori leadership, as signalled in the Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan.

In particular, the responses highlight the need for approaches that go beyond biomedical, health-focused thinking. Addressing the concerns raised in our research could assuage our participants’ worries and minimise maladaptive responses – but only if the approaches used are comprehensive and culturally meaningful.

Anna DeMello does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.