A feel-good NZ-shot video showing Fijian migrant workers being treated well by their Kiwi employer has garnered 350,000 views.

Joe Akari, chief executive of the Forest Industry Safety Council, doesn’t have huge expectations for his TikTok and Facebook videos. Forestry safety somehow doesn’t have the pull of adorable babies or Billie Eilish’s face warp.

If FISC creations get 10,000 views, that’s a success; when a recent one netted 29,000 that was pretty awesome.

READ MORE: * Calls for wider and permanent RSE rule changes * The hybrid harvester bringing lower carbon logging

And then there’s Troy Mason.

A Safetree video showing the lengths Mason, director of forestry company KTM Silviculture, goes to to make his migrant workers feel welcome and safe – introducing them into the local rugby team, taking them hunting and diving “with the boys”, renting solid homes for them and fighting for their visas – has more than 236,000 views on Facebook, plus 7800 likes, 3400 loves, and 500 almost exclusively positive comments. It’s got 108,000 views on TikTok.

Who would have thought hundreds of thousands of people wanted to watch other people having a good migrant worker experience?

KTM Silviculture is a Masterton-based family forestry contracting business. (Silviculture is the bit of the industry involving planting, pruning and thinning trees, as well as weeding around them. Harvesting is different.)

The company is relatively new – Mason founded it in 2019 with his wife Kelly – but it already has a good reputation. In 2021 it walked away the supreme winner at the Southern North Island Wood Council Training Awards.

Last year, with skills shortages biting in the industry, and needing to grow his team of around 30 mostly Māori staff to cope with an increasing workload, Mason employed his first group of Pacific Island migrant workers.

For the employment to be successful, he reckoned he had to manage the social and emotional impact on the 11 Fijians of being so far from home.

“Being away from your family for such a long time is hard,” he says. “I couldn’t do it. So I was aware I had to make them feel welcome, make them feel like part of our family.”

"Our industry needs migrant workers and not everyone wants to work in forestry." – Joe Atari, CEO, Forest Industry Safety Council

Rather than having them live in motels or campgrounds, Mason rented two local homes for the new staff. He also supported them to get three-year visas, giving them security, and making it easier for them to go back and forth to visit family.

But wellbeing was wider than that.

"When we first arrived it was hard for us,” says Jimoci Vatunitu Seasea, one of the Fijian silviculture workers. “We joined the Pioneer Rugby Club, and that’s how we settled in. We blend in with the boys, and then we just felt like we are home.”

“Troy cares about his workers,” says Niko Delai. “He’ll notice if we are feeling down and say ‘Okay we are going hunting today’.”

Mason also pays staff on an hourly rate to start, but as soon as they are working fast enough that a ‘per tree’ rate would earn them more, he shifts them.

“You pay a man what he’s worth,” he says. “And the benefit for me is these guys are reliable, they are hard-working.”

They are also loyal.

"Even if someone else tries to get us to go work for them, nah, we're loyal to Troy," Seasea says. "We're planning to stay with him for the rest of our lives!"

Critical shortages

The forestry industry is short of workers. In April last year, the Government agreed to special border exemptions allowing up to 300 silviculture specialists into the country. The industry had asked for 500 workers “immediately”, saying a shortfall would reduce planting volumes and plant survival rates, “with implications for future carbon reduction targets and supply of timber”.

Mason is not short of workers.

Akari says he first started hearing good things about KTM's employment of Pacific Island migrant workers when guys displaced from other crews started asking if they could work for Mason.

That's been possible for a few extra workers, but there are more men wanting to work for Mason than he has jobs for, Atari says.

Even so, Akari says he was as astonished as anyone when the Safetree video did so well on social media.

He doesn’t really understand why, but he’s hoping it starts conversations in the sector.

“We aren’t trying to say this is best practice. We are saying this is one boss and his crew and this is his approach. But our industry needs migrant workers and not everyone wants to work in forestry."

Akari also hopes the video’s positive message will act as a counterbalance to the more negative sides of the industry. Stories of exploitation of migrant workers, including poor living conditions, poor pay and inadequate training are as shocking in forestry as in other sectors like hospitality and horticulture.

“When I hear reports of exploitation, I worry this is what the industry will become known for. We build our reputation on our deeds, so even limited accounts of exploitation can damage how the industry is perceived.

“Right now public perceptions of forestry’s safety and sustainability practices are poor, and while we are well advanced in working to improve how we perform, we still have much to do to maintain our social licence to operate. Stories about exploitation will only compound our current challenges.

Which is where the video comes in. “We have an opportunity to demonstrate, as an industry, that our migrant workers are valued, well rewarded and supported.”

A grim record

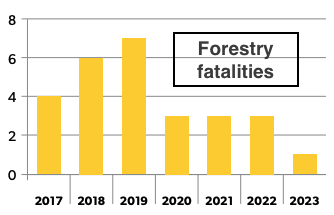

Unnecessary deaths and injuries have haunted forestry for decades. The safety council was set up in 2015 after a particularly grim 2014, when 10 workers died.

Thirty two people died between 2008 and 2014, making it the most dangerous sector in which to work in New Zealand at the time.

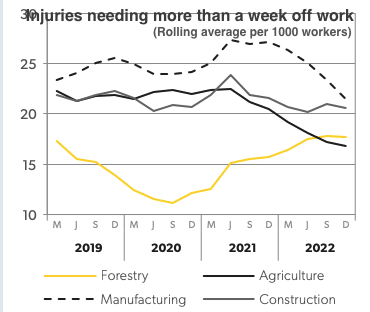

Things have improved since then, particularly in terms of fatalities, although having declined in 2019 and 2020, injury rates are increasing again.

While the Troy Mason video might not be directly about health and safety, Akari says workers who are treated well are more engaged, and less likely to get injured.

“These are all aligned. Keeping people safe is about people's behaviour and their attitude towards work. It’s why people invest in safety cultures. If you have a good culture in your company, having a good safety culture is easier," Akari says.

"Staff treated badly are less likely to be engaged and potentially that impacts on their attitude and their work practice, and that’s when risky behaviour comes in.”