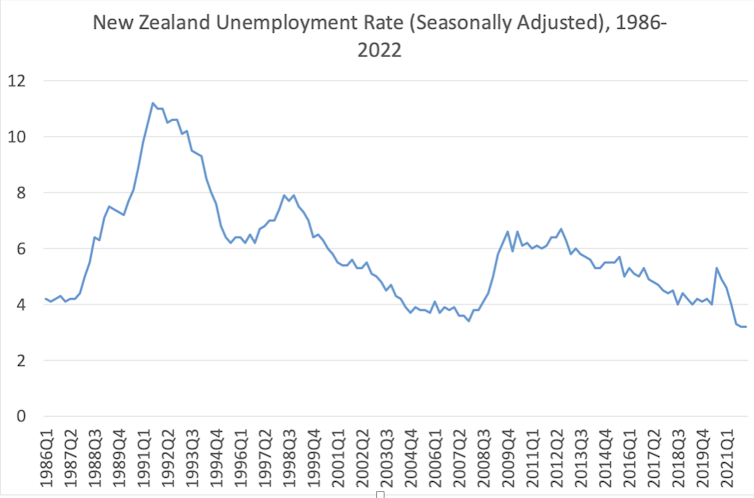

New Zealand’s unemployment rate hit a low of 3.2% in the fourth quarter of 2021 and again in the first quarter of this year. That’s the lowest the rate has been since at least 1986, both overall and separately for men (3.1% in both quarters) and women (3.3% in both quarters).

However, that low unemployment rate still represents over 90,000 people without jobs who are actively seeking work. So, why are some commentators starting to talk about “full employment” when it is clear that not everyone who wants a job has one?

Also, if businesses are struggling to fill positions, does this mean all workers will be able to flex their muscles in negotiations on pay and work conditions?

To understand New Zealand’s current labour market, we first need to understand the concept of full employment.

So what is full employment?

Economists define full employment as the absence of any “cyclical unemployment”, which is unemployment related to the rise and fall of the economy – also known as the business cycle.

As the economy reaches a peak in the cycle, employers increase production, requiring a high number of workers. The availability of these extra jobs reduces the number of unemployed, eventually reaching full employment.

But that doesn’t mean that when there is full employment there is no unemployment at all. There will still be some employment that is “frictional” (because it takes time for unemployed workers to be matched to jobs) and “structural” (because some unemployed workers don’t have the right skills for the available jobs).

Read more: Why income inequality is the policy issue to make or break governments

Rather than “full employment”, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) prefers to use the term “maximum sustainable employment”, which they define as “the highest amount of employment the economy can maintain without creating more inflation”.

Maximum sustainable employment reflects the RBNZ’s “dual mandate” to maintain low and stable inflation (between 1% and 3%) while “supporting maximum levels of sustainable employment within the economy”.

Clearly, in imposing the dual mandate on the RBNZ, the government believes full employment is an important goal. “Work, care and volunteering” is one of the domains of individual and collective well-being in Treasury’s Living Standards Framework, because these “are three of the major ways in which people use their capabilities to contribute to society”. Full employment means more people are contributing to their own and society’s well-being.

A worker’s job market?

So, what does full employment mean for low-income workers?

When there is full employment, it starts to become more difficult for employers to find workers to fill their vacancies. We are seeing this already, with job listings hitting record levels.

A tight labour market, where there are relatively more jobs than available workers, increases the bargaining power of workers.

Read more: Job guarantees, basic income can save us from COVID-19 depression

But that doesn’t mean workers have all of the power and can demand substantially higher wages, only that workers can push for somewhat better pay and conditions, and employers are more likely to agree.

This shift in bargaining power is why some employers are now willing to offer significant signing bonuses or better work conditions and benefits, including flexible hours or free insurance.

Low-wage workers will still feel the pinch

If you look closer at the types of jobs where signing bonuses and more generous benefits packages are being offered, however, you will quickly realise those are not features of jobs at the bottom end of the wage spectrum.

Many low-income workers are in jobs that are part-time, fixed-term or precarious. Low-wage workers are not benefiting from the tight labour market to the same extent as more highly qualified workers.

Nevertheless, a period of full employment may allow some low-wage workers to move into higher paying jobs, or jobs that are less precarious and/or offer better work conditions. That relies on the workers having the appropriate skills and experience for higher-paying jobs, or for increasingly desperate employers to adjust their employment standards to meet those of the available job applicants.

Read more: Not just a number: Defining full employment

Overall it is clear that not all low-wage workers benefit from full employment. Those who remain in low-wage jobs may even be worse off in a full-employment economy. If wage demands from other workers feed through into higher prices of goods and services it will exacerbate cost-of-living increases.

The RBNZ is already implementing tighter monetary policies to address high inflation, leading to higher mortgage interest payments for home owners. Renters will likely face higher rents as landlords pass on the increased interest rates. These higher housing and living costs will hit low-wage workers particularly hard.

Although a full employment economy seems like a net positive, not everyone benefits equally, and we shouldn’t ignore that some low-wage workers remain vulnerable.

Michael P. Cameron receives funding from Te Hiringa Hauora/Health Promotion Agency.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.