A 26-year-old Kiwi engineer and his former professor are trying to clean up one of the dirtiest metal recycling industries in the world

Who’d have known zinc is so useful? Humans need it for growth, healing, immunity, taste and smell. Plants need it for development, cricketers need it to protect their noses from sunburn.

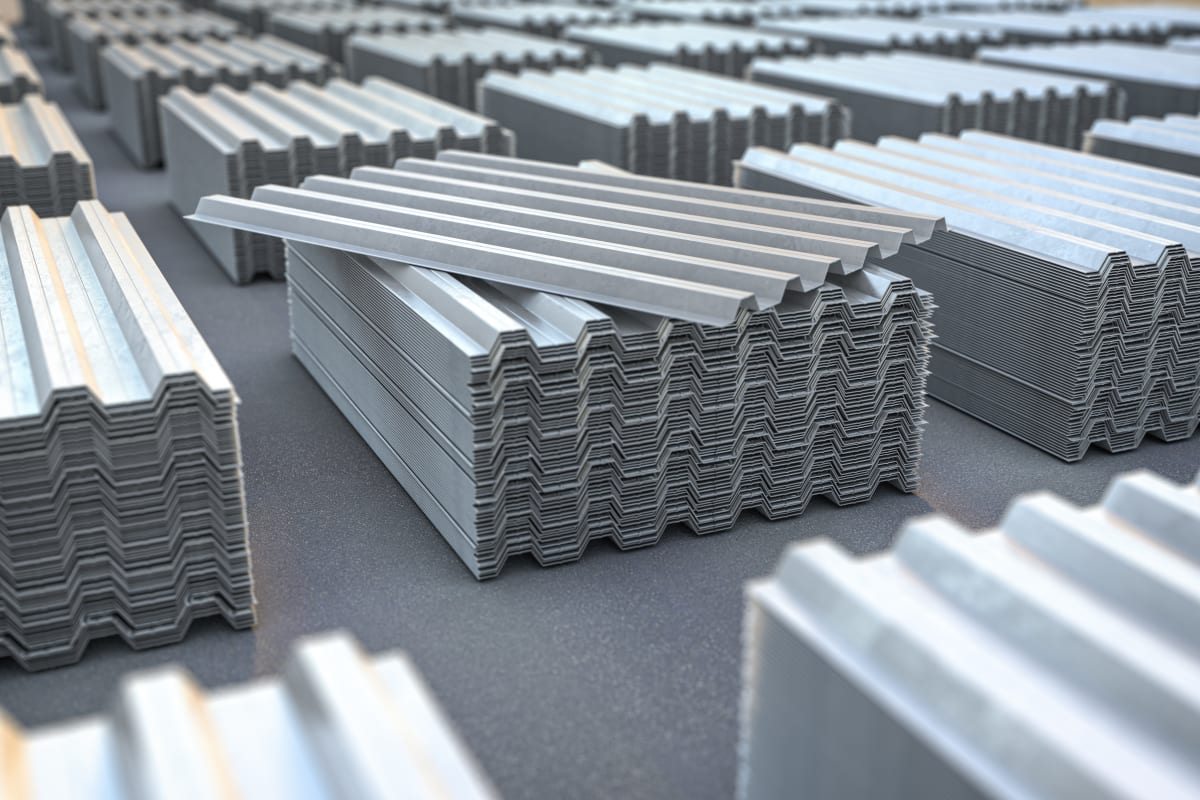

And it’s super-handy for making stuff too. Its corrosion resistance has seen it combined with copper to make brass for centuries, it’s also often in bronze. And the ‘tin’ on your roof? That’s probably galvanised steel – steel coated with zinc.

‘Galv’ is used extensively in construction, cars, agricultural equipment ... anywhere steel needs to be protected from rusting.

In short, zinc is the fourth most consumed metal in the world (after iron, aluminium and copper), with about half being used to make galvanised steel.

Mining and refining zinc ore is averagely bad when it comes to greenhouse gas production and global warming. There are worse metals; there are better. (For example, aluminium produces more CO2 when it’s made than zinc, steel produces less.

There’s an increasing push to recycle more old galvanised steel and other zinc-containing materials back into useable zinc.

Recycling stops more zinc needing to be refined, and you can basically get pure zinc out of old zinc products and back into new ones over and over again. The quality doesn’t degrade.

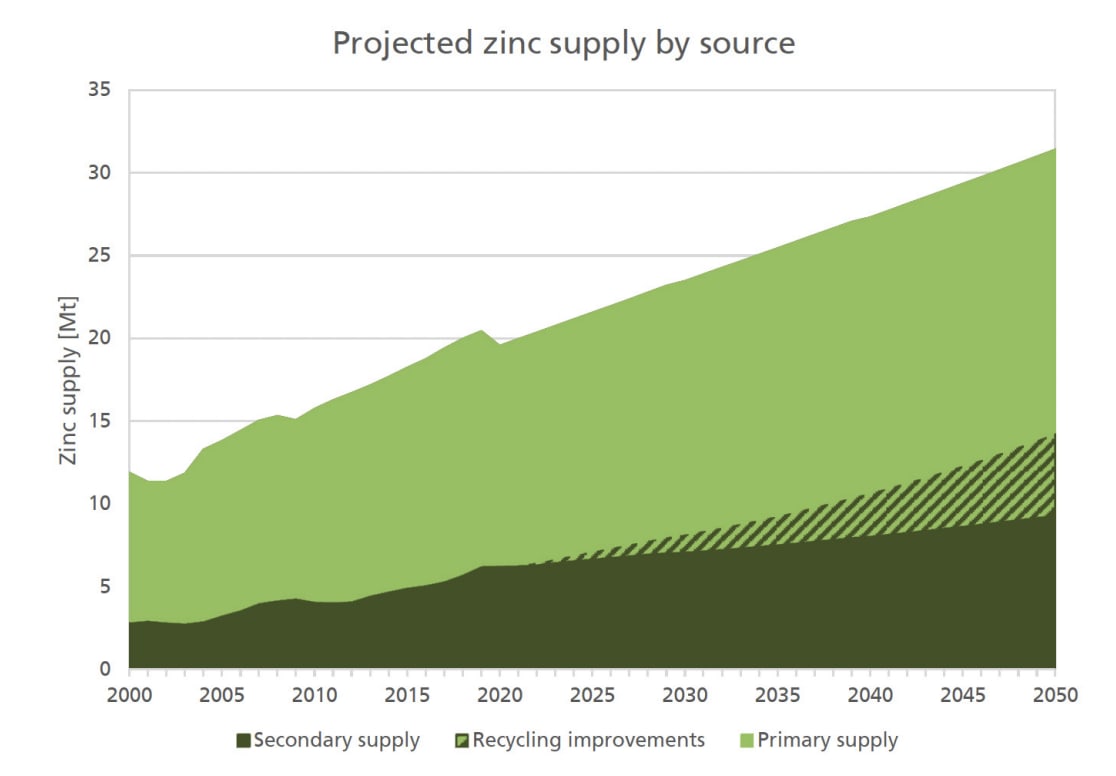

Almost 40 percent of the zinc used in the world is from recycled zinc, and that is set to increase to above 50 percent by 2050, according to the International Zinc Association

Unlike the deal with many other metals, recycling zinc using the technology we have at the moment actually produces significantly more greenhouse gas emissions than mining the metal from scratch.

According to the zinc association, global mining operations produce an average of 3.64 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per tonne of zinc. That figure is 6.5 tonnes of CO2-e for recycled material.

The recycling process is also expensive and wasteful.

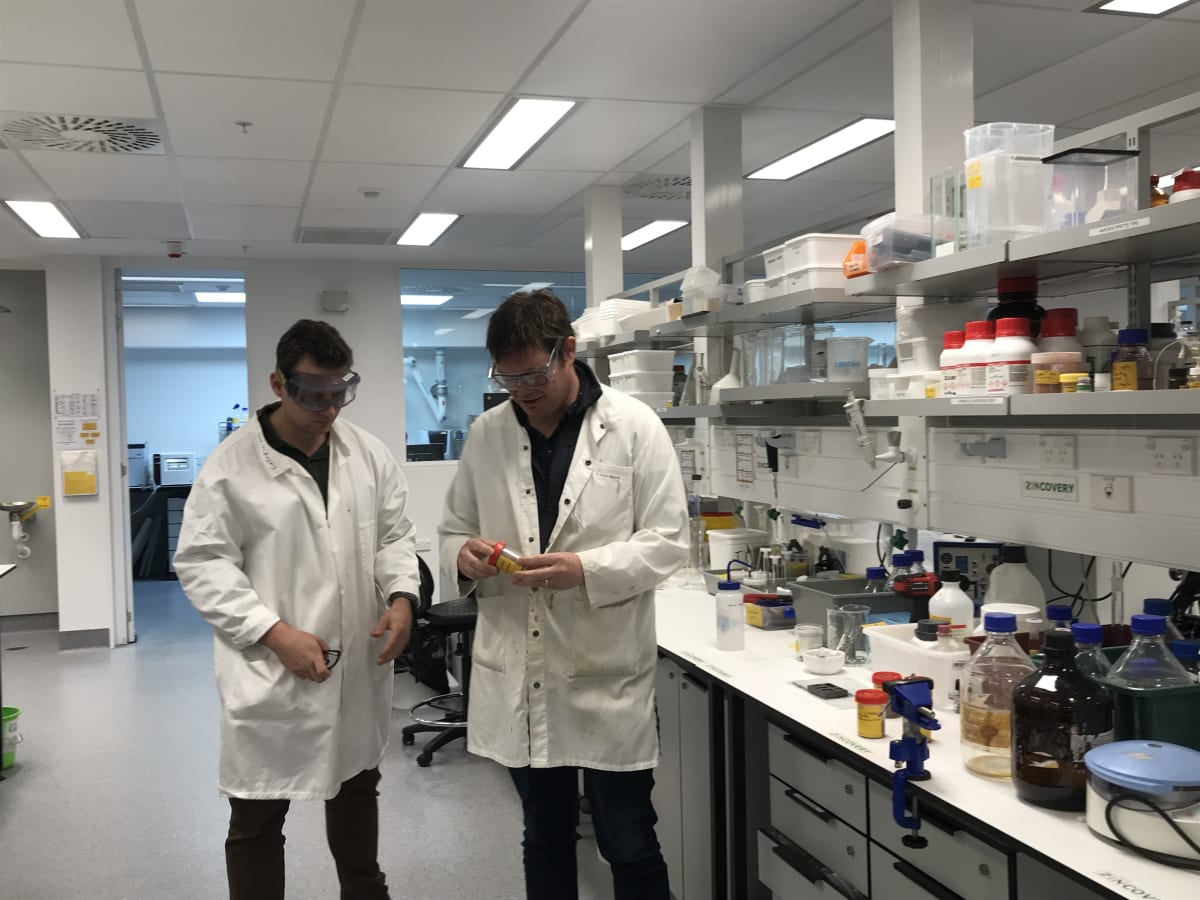

Which is where a New Zealand company spun out of the University of Canterbury comes in. Zincovery, founded by 26-year-old engineer Jonathan Ring and his former professor, Aaron Marshall, has invented technology which, in lab trials at least, can salvage zinc from waste using 70 percent less energy than current methods, and producing a sixth of the carbon dioxide - less than one tonne CO2 per tonne of zinc.

The process is also 30 percent cheaper, Ring says.

“Zincovery’s technology has the promise to significantly improve the environmental footprint of the multi-billion dollar global zinc recycling industry,” says the Zincovery CEO.

It’s early days. Zincovery will today announce it has completed a $3 million early stage venture capital funding round to take its research off the lab bench and into a pilot plant. Investors include New Zealand funds like Icehouse Ventures, K1W1 and the Climate Venture Capital Fund, as well as Austrian billionaire Wolfgang Leitner.

Tucked in a corner of the Engineering School carpark, the pilot set-up will consist of a couple of shipping containers and some small chemical storage and water treatment containers. This should allow Ring, Marshall and their six-person team (set to rise 10 shortly) to trial small-scale production.

If everything goes well with the pilot, perhaps by the end of 2024, there will be another $10 million or so needed for a larger demonstration plant.

And if that is successful, there will be tens of millions more in capital raising required to move to full-scale production.

Realistically, getting that first recycled zinc out of a commercial factory could be five years down the track.

So-called “deep tech” projects aren’t cheap or easy.

A gnarly problem

The ZIncovery story started in 2018 with Aaron Marshall, an energy technology specialist, professor at Canterbury University’s engineering school and principal investigator at the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology.

“I was at a galvanised steel place in Christchurch and they mentioned in passing they had an issue with waste and how much zinc appeared in this waste. It was a huge resource being sent to landfill.”

It seemed like a hard problem that needed fixing, and he mentioned it to Ring, then just finishing up his degree and looking for a job in industry.

“I didn’t have any ambitions about doing post-grad study, but this was a practical project and great for the environment, and Aaron said he wanted to turn it into a business if it was successful. I hadn’t realised post-grad study could be a pathway to that.”

It’s been a tough four years. The first iteration - technology to remove zinc from scrap galzanised steel - won the prestigious Callaghan Innovation C-Prize and raised $1.2 million in seed funding. But a market study showed it wasn’t going to work financially.

“One of the key things we had to prove was the Chinese market because China produces 65 percent of the world’s galvanised steel,” Marshall says. “Initial valuations were promising, but it was opaque.

“So we spent around $100,000 getting good market information and found that yes, the Chinese mills produce a lot of waste, but there was low zinc content in that waste and there were low disposal costs for the waste. Our technology was only viable with high disposal costs and a high zinc content.”

From the ashes

Everything had been going so well, Ring remembers, and then suddenly, disaster. “We realised we were not going to be able to get capital - we didn’t see a pathway for a startup to enter this market.”

The board got together - Ring, Marshall, Sean Malloy from sustainable green tech companies LanzaTech and Avertana, and entrepreneur Daniel Batten - and they gave the Zincovery team three months to pivot the technology and the business.

“We knew there were lots of opportunities in the metal recycling space,” Ring says. “So we said ‘Let’s spend three months seeing if we can find a big enough market and something where we have a competitive advantage based on skills of the team and our existing IP.’

“If not, we’d close down and return money to investors.”

“It certainly sharpens the senses,” Marshall says. “Most of the team are technical people. Suddenly it was all about market research.”

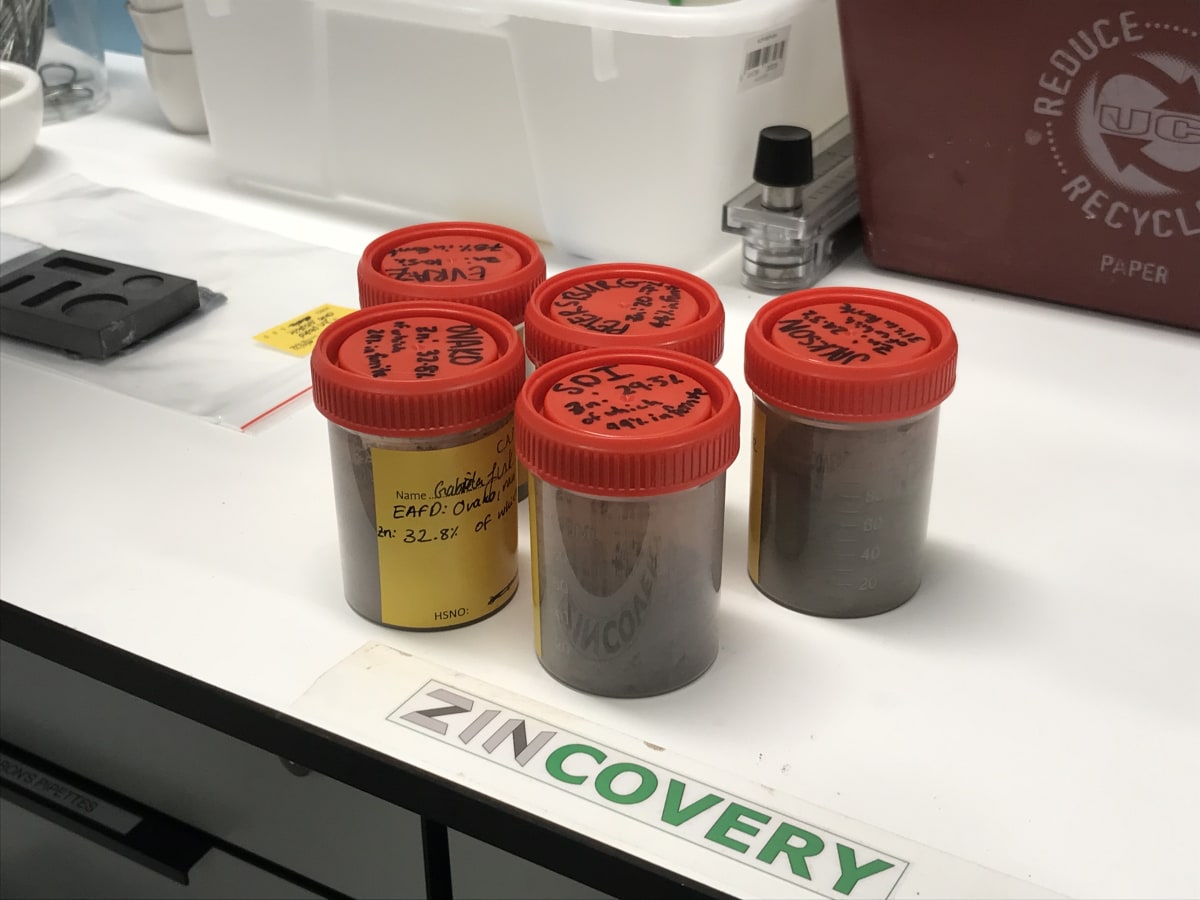

In between working like crazy, the Zincovery team got hit by Covid, including Ring being impacted by long Covid. But they found the market segment they needed - furnace dust from scrap recycling.

Imagine a pile of scrap steel going into a furnace, being melted down into new steel. The molten steel comes out the bottom, but zinc and other additives shoot out the top in the form of dust and are collected in a bag.

Think a massive vacuum cleaner.

The challenge is to get the zinc and other metals out of the dust, and produce zinc to a 99.995 percent purity.

“A normal-sized steel mill will produce tens of thousands of tonnes of this hazardous waste dust in a year,” Ring says. “Something like 70 percent of recycled zinc comes from furnace dust, and it has a zinc content between 15 and 35 percent.”

There is already a process to remove zinc from dust, using what is called a Waelz Kiln. But Ring says Zincovery’s advantage is its kiln operates at a much lower temperature, which means it will use 70 percent less energy, significantly reducing emissions and bringing costs down.

So far, investors like the idea. The latest capital raise was over-subscribed, Ring says. They were originally looking for $2 million, but “were quietly hoping for more”. Even taking $3 million, Zincovery had to turn away quite a few investors, he says.

“When a capital raise goes, it goes.”

The biggest investor is Icehouse Ventures, which took a stake in the previous funding round and now holds 22 percent.

Chief executive Robbie Paul says it’s helpful New Zealand has developed some expertise over recent years with companies using sustainable technology to extract value from the metals waste stream.

LanzaTech, now US-based, captures emissions from steel mills and landfills and turns them into fuels and chemicals. Avertana uses waste slag from steel manufacturing to produce minerals and chemicals. Mint Innovation recycles e-waste and opened its first commercial biorefinery in Sydney in August.

Zincovery director Sean Molloy worked with LanzaTech and is a co-founder of Avertana.

“Icehouse investments are biased towards companies that can do more than make money, but do good as well,” Paul says. “We believe companies with missions bigger than just making money are going to attract the best talent and investors, and that has a compounding effect on their success.”

He’s not put off by the trials that have consumed much of the first three years of Zincovery’s life - quite the reverse.

“Every company that is a headline success has gone through hell and back - sometimes in the early stages,” Paul says. “Resilience and tenacity is a baseline must for us. We talk about founders who have the audacity to put everything on the line.”

He says Ring has the advantages of youth (being closer to the cutting edge of innovation and being unencumbered by family and therefore able to live cheaply) and also having a mix of technical and marketing skillsets.

“Never underestimate young founders, especially when they are mission-driven and an eternal optimist.”