The benefits of AI can be debated. But one thing we're all sure about is that massive server farms packed full of hundreds or thousands of high-end AI GPUs, each consuming hundreds of watts, soak up a lot of power. Right?

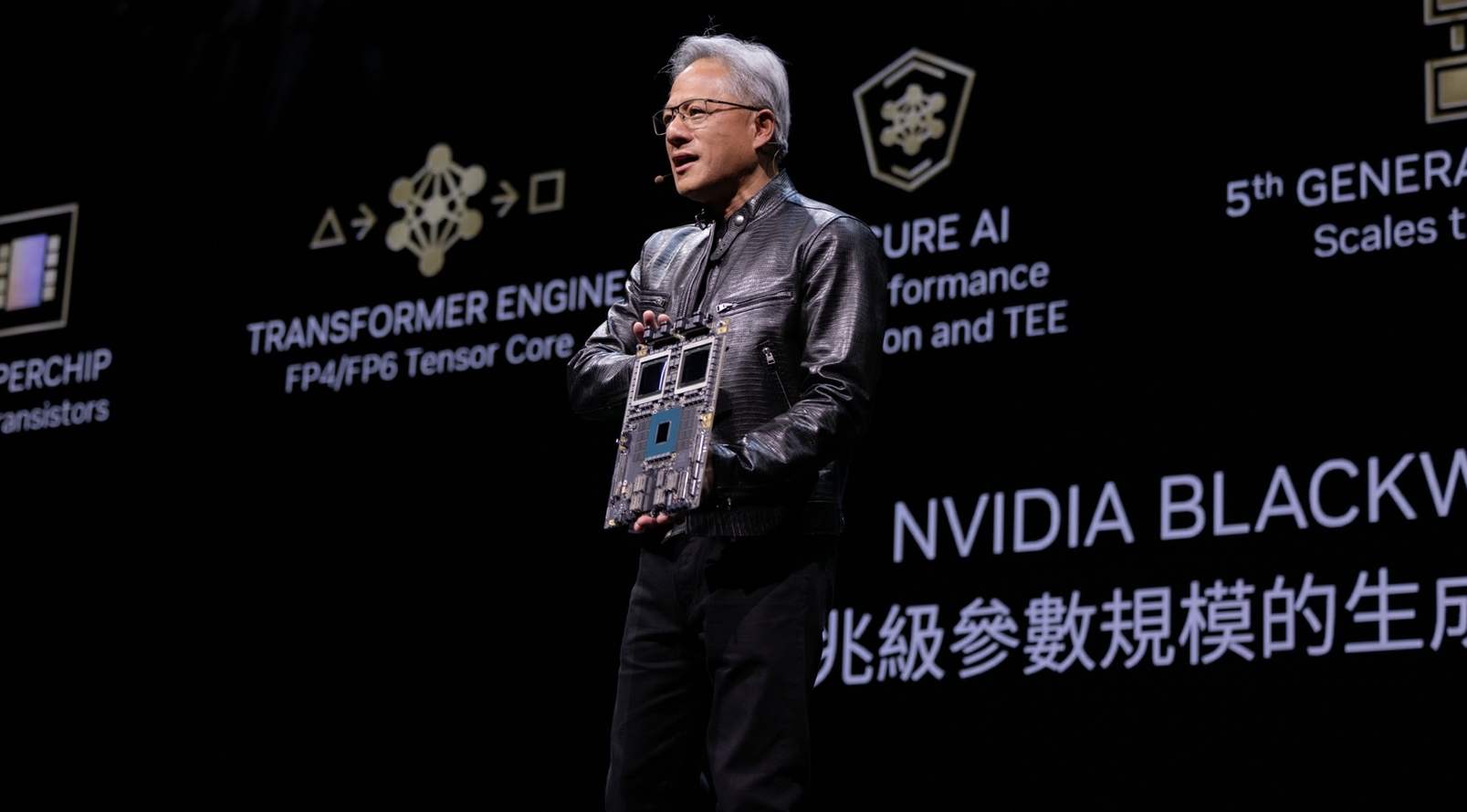

Not Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia whose catchphrase has become "the more you buy, the more you save", in reference to his company's stratospherically expensive AI chips. Perhaps inevitably, Huang has a similar take when it comes to the power consumption associated with the latest AI models, which mostly run on Nvidia hardware.

Speaking in a Q&A following his Computex keynote, Huang's point is firstly that Nvidia's GPUs do computations much faster and more efficiently than any alternative. As he puts it, you want to "accelerate everything". That saves you money, but it also saves you time and power.

Next, he distinguished between training AI models and inferencing them and how the latter can offer dramatically more efficient ways of getting certain computational tasks done.

"Generative AI is not about training," he says, "it's about inference. The goal is not the training, the goal is to inference. When you inference, the amount of energy used versus the alternative way of doing computing is much much lower. For example, I showed you the climate simulation in Taiwan— 3,000 times less power. Not 30% less, 3,000 times less. This happens in one application after another application."

Huang also pointed out that AI training can be done anywhere, it's doesn't need to be geographically proximate. To put it his way, "AI doesn't care where it goes to school."

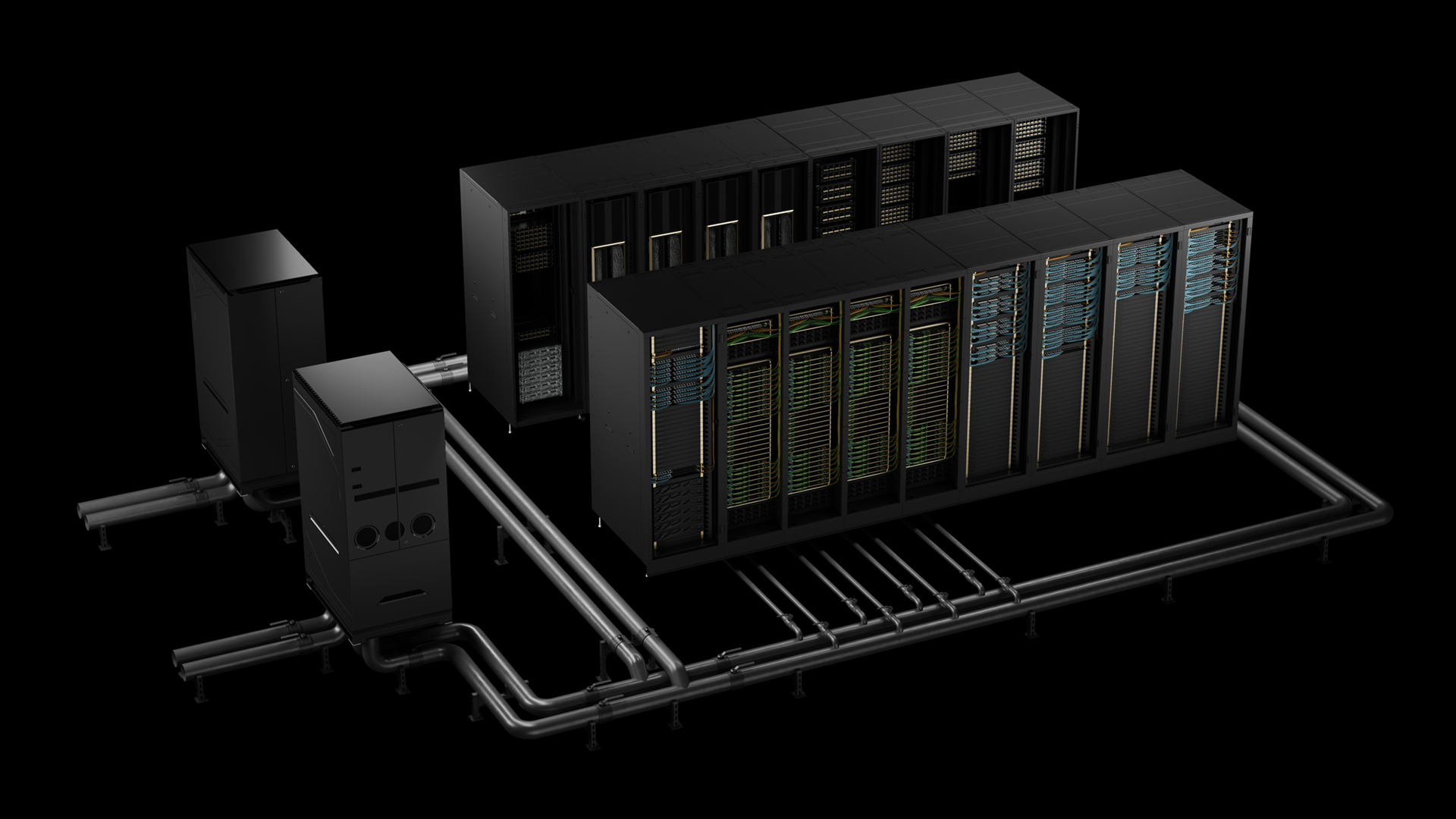

"The world doesn't have enough power near population. But the world has a lot of excess energy. Just the amount of energy coming from the sun is incredible. But it's in the wrong place. We should set up power plants and data centres for training where we don't have population, train the model somewhere else. Move the model for inference everyone's closer to the people—in their pocket on phones, PCs, data centres and cloud data centres," Huang says.

You can see his points, and yet... Let's put it this way, Huang's take is somewhat selective. It's hard to pin down exactly how much energy is currently being used to train and inference various AI models. The World Economic Forum recently estimated that AI-related power consumption is growing at a rate of between 26% and 36% annually and that by 2028, it will match that of a small country like Iceland.

Now, Huang's argument would be that this is or will be offset by lower consumption elsewhere. But that's only true for things that would otherwise be done without AI. The problem is that it's often tricky to tell the difference.

Whether you're using AI to create code, write a business plan, or create content, it's hard to pick apart the impact it has on the production process. Maybe using AI meant you edited those photos much more quickly and efficiently. Or maybe it just added an extra layer of polish to a video production at the end.

Or maybe you're just doing something with AI that would have been totally impossible without it, and every joule of energy you use is a net gain in the AI energy usage ledger. Equally, maybe AI lets you do things faster and therefore do more things. Each task is more efficient, but you move on to the next thing much more quickly and use much more energy as a consequence.

Catch up with Computex 2024: We're on the ground at Taiwan's biggest tech show to see what Nvidia, AMD, Intel, Asus, Gigabyte, MSI and more have to show.

Huang's comments about energy availability are pretty specious, too. Sure, there may be more than enough solar power to do everything we want, many times over in a totally sustainable fashion. But, really, so what? That's not, predominantly, where our power currently comes from.

Just like his favourite "the more you buy, the more you save" quip there's obviously a strong element of "he would say that". But, broadly, it's hard to dismiss the notion that the energy footprint of AI is problematic. It's equally hard to imagine that AI is going to push net energy usage down any time soon, whatever Huang claims.

That day may come. Ironically, it may be with the help of AI to design a more efficient way of doing things that we get there. Who knows, maybe AI will help us work out how to make fusion energy production genuinely practical. But for now, just as it doesn't feel like saving money when an AI start-up has to pay $40,000 a pop for one of Nvidia's AI GPUs, it's not easy to square the race to build all those massive AI farms with claims of reduced power consumption.