There is a fine line between madness and sanity and if we are honest, most of us tread that line on a regular basis, even if unawares.

The exhibition, Notes on Madness, highlights medical cases found in the archives of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) in Bengaluru between 1920-1970, in an attempt to engage with society and debunk the many myths surrounding insanity.

Funded by the Wellcome Trust, the project is part of Mindscapes, an international cultural program that seeks to bring awareness on mental health. It was curated by Quicksand Design Studio and designed by Studio Slip, in collaboration with NIMHANS.

According to the exhibition’s curator Kamini Rao and founder of Studio Slip, the entire process was mentored by Dr. Sanjeev Jain. “He was the head of psychiatry at NIMHANS. Though he has since retired, he was an instrumental part of this research project from the time of its inception,” says Kamini.

It is the vast unknown about mental health that makes the average person shrink from its instances in their circles. Still, how does one begin to plumb the depths of such a vast topic to present it as an exhibition? A team of designers and researchers roped in a psychiatrist, Sinjini Ghose and together, they dug into the archives.

“It was a time-consuming task,” says Kamini. “Not many records where digitised, so we had to scour through them manually. Trawling through digital archives and opening countless PDFs were no laughing matter either.”

However, in the process, the team discovered a treasure trove of material and artefacts, “we can curate a few more exhibitions with the stuff we unearthed during our research.”

Eventually, they narrowed their work to three main areas of mental health — psychosis, neuro syphilis and hysteria. “The doctors at NIMHANS in those times had also focused on these three conditions to break the stereotype about severe mental health illnesses, Hence, each of these were important in the history of mental health in Bengaluru.”

Psychosis is a condition where a person loses touch with reality, affecting their thoughts, emotions and perceptions.

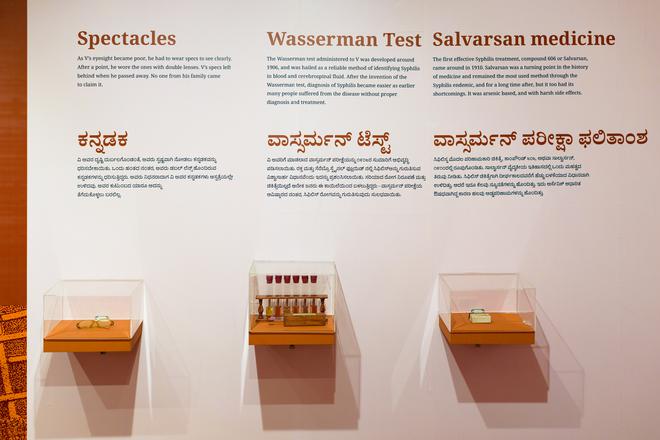

Interestingly, neuro syphilis was called ‘firang disease’ as it was brought into the country by the foreign rulers; it was one of the first instances of people realising there is a physiological reason for mental disease and that the particular illness can be transmitted. There was no cure for the disease, syphilis until the discovery of penicillin.

Looking up hysteria, the team found that throughout history and all over the world, this condition centered only around women. “The notes on women from the 20s show most of them were blindly diagnosed with hysteria irrespective of background, class or caste. It also showed how women are medically treated differently from men.”

“Hysteria has different names today and it is broken down into like more specific symptoms and illnesses. However, they don’t use that term anymore and diagnosis pertains to all genders.”

An important finding came to light from the team’s research into the history of mental illness — the political, religious and socio-economic landscapes played a huge part in one’s mental wellbeing and “it was important to understand this if we were to progress as a society”

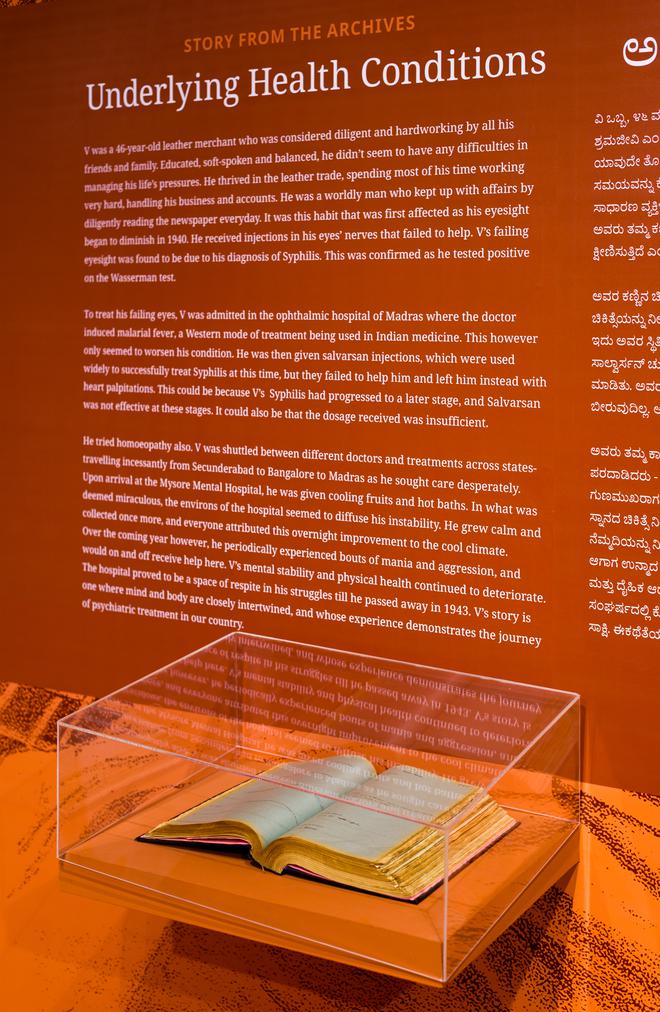

At the exhibition, one can read from the original record book of the 1920s, though names have been redacted in deference to patient confidentiality.

“All the exhibits are in Kannada and English to cater to everyone — visitors to NIMHANS as well as those seated in waiting rooms. We have tried to keep the content light and informational in order to help people understand better and to avoid any trigger warnings as well,” says Kamini.

“When people engage with the stories or cases from the records they understand that they are not alone; these things have happened throughout history and it’s not just them, despite what society or their community says.”

Some of the exhibits include items left by patients; while some can be put down to general forgetfulness or removed to prevent self harm, some have been purposely discarded by those wanting to start a new chapter in their lives. For example, a woman who was married off young and forced to have children was ‘diagnosed’ with hysteria when she could not cope. When she was discharged from the hospital, she discarded her mangalsutra and toe rings as she did not want to associate with them anymore.

Other exhibits include an original ECT or Electro Convulsive Therapy machine made in Bengaluru in the 1940s, a brain of a schizophrenic patient which looks like any other brain (since there is nothing wrong with it physically), a bath tub used for hydrotherapy (to cool the body in cases of brain fever which was a symptom of neuro syphilis) and much more.

Apart from these three sections on mental illnesses, there is also an entire section dedicated to caregivers. “Caregiver accounts were archive and we recorded their stories so visitors could access them on headphones, both in English and Kannada. We’ve also included stories of modern day caregivers. While this exhibition is open to the public and students, we know a majority of people who will be actually going there are the caretakers who are sitting around for hours while their loved ones are undergoing treatment. We wanted to ensure they were also being heard.”

There are a lot of interactive elements in the exhibition as well as audio, lots of illustrations, so that people can follow the depiction as well as the information.

Kamini says, “We have a lot of reflection points with cards pertaining to each section where visitors can pen their thoughts. We’ve used the Systemic View to arrange the exhibition, so one realises it’s not just an individual, but a circle of friends and family that gradually expands to include one’s job, their past, class and social upbringing. We want to emphasise mental health issues are not your fault or your family’s fault. Variables such as genetics and trauma play a part too.”

Exhibits in the form of illustrations, videos and comic books are at the doorway to make the content more relatable to the younger generation. Apart from being presented in easy-to-read fonts at different heights for all visitors, it is also wheelchair friendly and has an ample seating area.

Notes on Madness is on at NIMHANS till June 30