The fastest animal on land is the cheetah, capable of reaching top speeds of 104 kilometres per hour. In the water, the fastest animals are yellowfin tuna and wahoo, which can reach speeds of 75 and 77 km per hour respectively. In the air, the title of the fastest level flight (excluding diving) goes to the white-throated needletail swift, at more than 112 km per hour.

What do all of these speedy creatures have in common? None of them are particularly big, nor particularly small for the group of animals they represent. In fact, they are all intermediately sized.

The reason for this is a bit of a mystery. As animals increase in mass, several biological features change as well. For example, in general leg length steadily increases. But clearly long legs are not the answer, since the largest land animals, like elephants, are not the fastest.

But my colleagues and I have taken a key step towards solving this mystery. By using a scaleable, virtual model of the human body, we were able to explore the movement of the limbs and muscles, find out what limits speed, and gain important insights into the evolution of the human form over thousands of years.

From a mouse-sized human to a giant

Since the early 2000s scientists have been building OpenSim – a freely available, virtual model of the human body, complete with all its bones, muscles and tendons.

This model has been used in various scientific studies to understand human movement, explore exercise science and to help model the effects of surgery on soft tissues.

In 2019 a group of Belgium researchers took this one step further, and built a physics-based simulation using OpenSim. Rather than telling the model how to move, they asked it to move forward at a certain speed. The model then figured out which combinations of muscles to activate so it could walk, or run, at the prescribed speed.

But what if we took this even further and scaled the model down to the size of a mouse? Or what if we scaled the model up to the size of an elephant? Then we could see which models could run – and how fast.

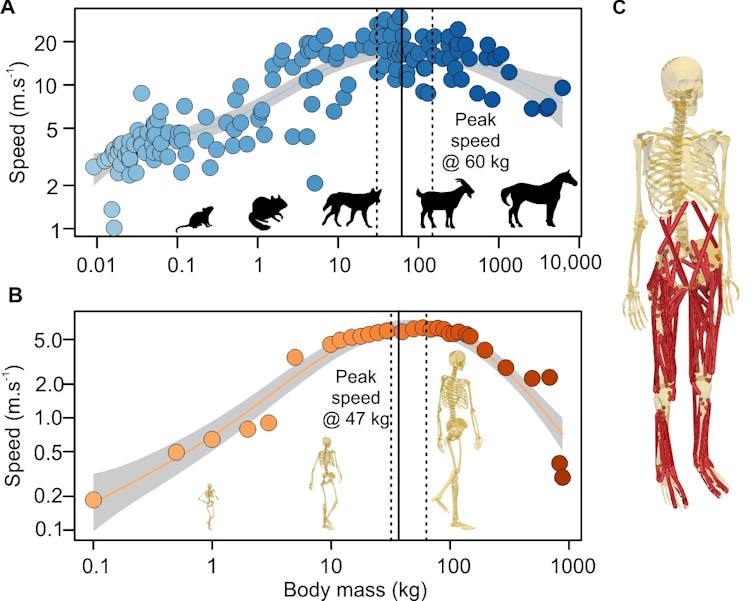

This is exactly what my team did. We took the standard human model (75kg), and made smaller and smaller models down to 100 grams. We also made the models bigger, up to 2,000kg, and challenged them to run as fast as they could.

Getting the mass just right

Several fascinating things happened when we did this.

First, the 2,000kg model couldn’t move. Nor could the 1,000kg model. In fact, the largest model that could move was 900kg, suggesting an upper limit to the human form. Beyond this size we need to change shape in order to move.

We also found that the fastest model was not the biggest nor smallest. Instead, it was around 47kg, a similar weight to an average cheetah. Crucially, we could look under the hood and see why this was so.

The curve that explains the shape of the maximum running speed with mass is the same shape as the curve, which explains the max ground force with mass. This makes sense: to move faster, you need to push off the ground harder.

So why couldn’t larger models push harder off the ground? It appeared the larger models were limited by their muscles.

A muscle’s ability to produce force depends on the cross sectional area of that muscle. And as animals increase in size, the mass of their muscles gets bigger faster than their cross-sectional area.

This means the muscles of larger animals are relatively weaker. The muscles begin to “max out” above the max speed – and so the model has to slow down.

At the other end of the spectrum, the miniature models have relatively stronger muscles, but have a problem with gravity. They are just too light. They try to push on the ground to produce a large force, but this just causes their body to leave the ground earlier.

To try to produce more force on the ground, they crouch their limbs, just like mice or cats do. This allows them to stay on the ground longer and so produce more force, just like you might when doing a standing jump. But this takes time. And the longer you take to produce force, the slower your stride will be and you still won’t run faster.

So a trade off between ground force and stride frequency begins, and doesn’t end until you reach the intermediate size, where your mass is just right.

As fast as we will get

What might all of this say about human evolution?

We know throughout history that the size of modern humans and extinct human species – a collective group known as “hominins” – has varied significantly, from the roughly 30kg Australopithecus afarensis that existed roughly 3.5 million years ago, to the roughly 80kg Homo erectus from nearly 2 million years ago.

So generally body mass has tended to increase – and presumably so too has our running speed. Homo naledi, which existed around 300,000 years ago and weighed around 37kg, and Homo floresiensis, which existed around 50,000 years ago and weighed around 27kg, must have had to sacrifice some speed for their small size.

The average body mass of modern adult humans is around 62kg – a little heavier than the 47kg peak weight that our modelling found, but still close to that ideal size.

Interestingly, many of our fastest long distance runners such as Eliud Kipchoge weigh around 50kg.

So based on our new research, we now know humans today are about as fast as we will get – without large changes to our muscular form.

Christofer Clemente receives funding from an ARC Discovery grant (DP230101886)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.