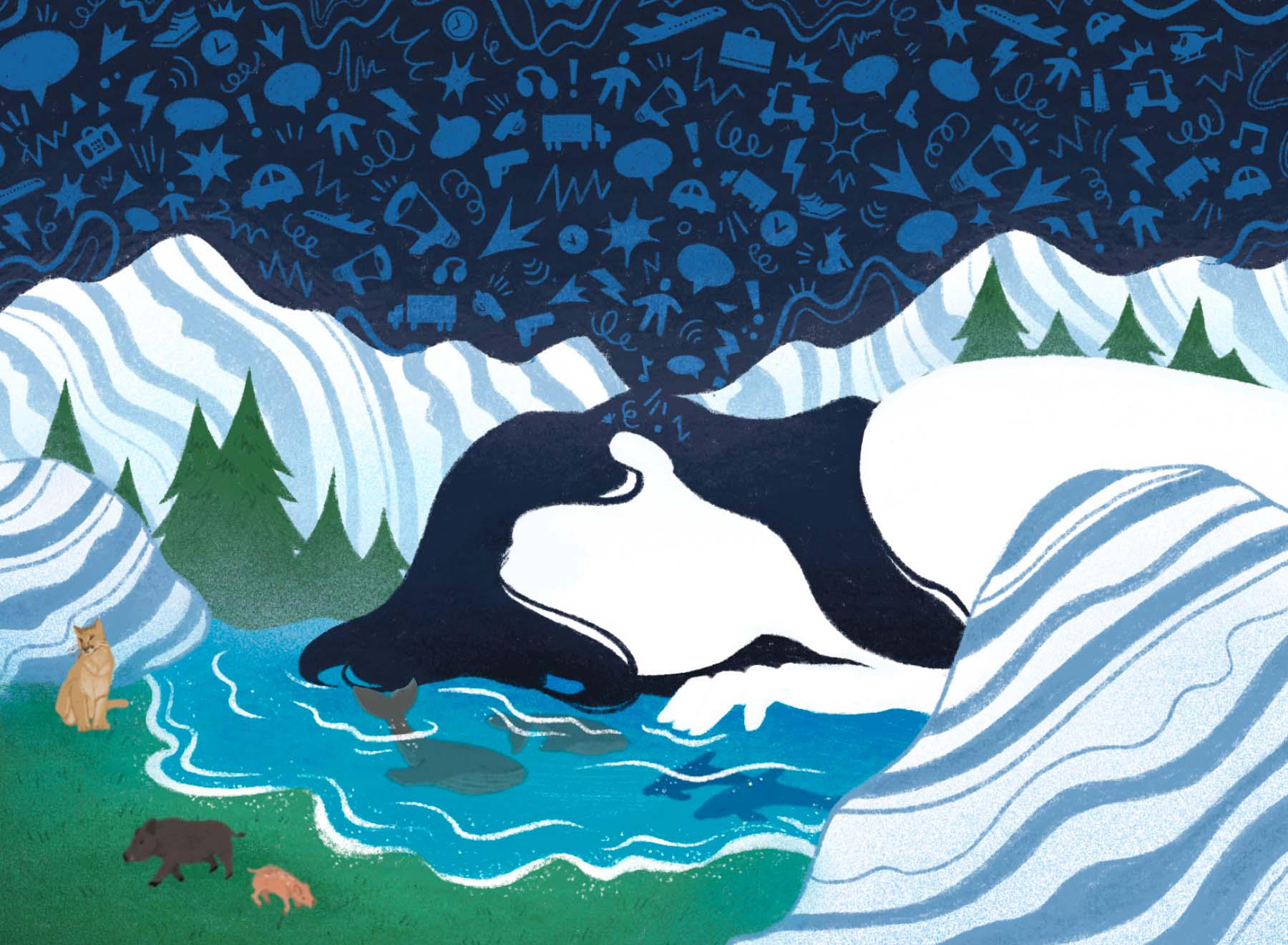

As the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the world, much human activity ground to a standstill. That rare pause led to a string of fascinating events. The Himalayas could be seen from the city of Jalandhar for the first time in decades as air pollution dropped. Animals strolled into cities as we retreated into our homes. Wild boars roamed the streets of Haifa in Israel, dolphins played in the Bosphorus Strait in Turkey, and cougars strolled through the streets of Santiago in Chile. Perhaps most noticeable of all was the silence in the oceans, with ships coming to a halt in ports across the world. Amidst the quiet, whales may have significantly broadened their song repertoire using a greater variety of sounds than they previously had. Scientists observing that change still don’t have a very good idea of what it means.

Amanda Bates, a biology professor at the University of Victoria, remains fascinated by the events of 2020. “Before this event, it was impossible to shut off noise around the world, but we did this—on land, in our cities, as well as in our oceans,” says Bates.

We now know so much more about the impacts of the omnipresent noise we have introduced in every corner of our planet. The noise is everywhere. It’s hurting us and every human and animal around us. Bates calls that brief, quarantine-spurred lull in the incessant hum of humanity the “anthropause.” It was a lesson in humility and, maybe, a lesson in ethics.

This ethical dilemma involving who we hear and who we decide to shut out is something Matt Jordan, professor of media studies at Penn State University in Pennsylvania, has been thinking and writing about for a long time. He says noise is just a catch-all term for any and all unwanted sound. “There are all kinds of things that teach us how to hear, that teach us what is a good sound, what is a beautiful sound, what is a comfortable sound, and what is unwanted, what is jarring, what is dissonant,” he says.

He is talking about relatively benign sounds: the loud music from a neighbour’s yard, the din of a street hockey pickup game under your window, or the noise of a busy street you walk down every day on the way to work. And as benign as that noise is, most of us don’t want it.

“There is a discourse that is always trying to tell us that having to hear other people is an awful thing and that the only adequate response to that is to live in some sort of an acoustic cocoon,” says Jordan.

In some ways, it’s always been this way. In an article for The Conversation, Jordan walked readers through the past 400 years of history of noise complaints, mostly from well-off white guys. Blaise Pascal, Charles Dickens, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Scottish polemicist Thomas Carlyle all get a mention. Poor Carlyle spent a fortune trying to soundproof his London house. “Acoustic comfort to a certain degree comes to stand for quietness,” says Jordan. “We live in this world full of sound, so what we do is we start selling the idea that you should be able to control it. You should only have your wanted sound. That’s the sound of the good life!”

In the present day, soundproofing our lives has become much more accessible. Technology, like noise-cancelling headphones, has democratized our ability to live in an acoustic cocoon of personal comfort. A lot more of us can afford a pair of fancy earbuds than a home renovation.

But not all noise we have to endure is benign. Some of it is downright sinister.

In October, the Public Order Emergency Commission took a hard look at the federal government’s invocation of the Emergencies Act during the “Freedom Convoy” protests at the beginning of 2022. During the convoy, protesters driving trucks blared their horns for hours on end, both during the day and deep into the night. “The long-term effects are loss of hearing, loss of balance, some vertigo triggered by the sound of any horn now,” testified Victoria De La Ronde, identified in transcripts of the commission as a visually impaired resident of downtown Ottawa. “The sounds of the horns, the sounds of the very, very loud music, the sounds of the people, with lots of voices coming from all different places, all was disconcerting and just completely eliminated my ability to negotiate my environment independently.”

The use of sound was a disruptive and aggressive strategy that had profound health impacts on Ottawa residents. “The noise was used as an instrument of terror,” says Tor Oiamo, an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University, who is studying how city noise affects human health. “It kept going during the night. You don’t have to go through too many nights without sleep before you start getting severely stressed out.” For some, the noise of the protests was reminiscent of a torture tactic—military and intelligence agencies have been exploiting the impact sound has on physical and mental well-being for some time.

Oiamo’s research has shed some light on how sound hurts us, both on a day-to-day basis and in the long term. He has worked with organizations like Toronto Public Health, whom he helped build detailed maps of noise levels and exposure impacts. When overlayed with health data those organizations have, the maps can, in part, help determine the long-term health impacts of noise exposure in different areas of a city.

We measure sound using a unit called decibel (dB)—the higher the number, the louder the sound. A normal conversation is about 60 dB. A whisper is about 30 dB and a nearby siren around 120 dB, which is about the same decibel level as that of an average rock concert. A quiet residential area will register about 40 dB and a busy highway about 80 dB.

With over twenty years of data, Oiamo assembled a groundbreaking study that looked at the long-term health impacts of noise. His study focused on individuals between thirty and 100 years of age who had been residents of Toronto for at least five years. He found that exposure to noise increases the risk of developing an ischemic heart disease. Exposure to noise above 53 dB poses an 8 percent risk for ischemic heart disease, and that increases by another 8 percent for each 10 dB. “So if you are at 53 dB, it’s an 8 percent increase. At 63 dB, you have a 16 percent increase, and so on,” explains Oiamo. There is also a significant correlation between noise and stress, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Prolonged proximity to anything above 85 dB will permanently damage human hearing. When exposed to sounds louder than 110 dB, we experience discomfort, and anything louder than 120 dB will cause pain. An average leaf blower comes at anywhere between 80 and 85 dB, and a jet engine registers about 130 dB from 100 feet away. A horn on a commercial truck can be as loud as 150 dB.

The path toward more holistic approaches to the ethics of sound may have to start at our doorsteps.

There is an environmental justice component to noise in our cities. Wealthy neighbourhoods tend to be quieter, while low-income neighbourhoods are often much louder, further eroding the quality of life and health outcomes for people who are already at a disadvantage because of their socio-economic status. People in those neighbourhoods can generally expect to endure more noise produced by planes or traffic, for example. The big difference is that we now know there are social and physical costs to living in noisy environments.

Bates wonders what the future holds, now that the evidence on how noise impacts life on Earth, including our life, is in. “We may know it’s good for us, but we may not always be able to prioritize as a society how to get there,” she says. What the pandemic showed us is that a global change in human behaviour is possible but that it comes at a cost. “How do we maximize what is possible?”

“The simple answer is a million little things,” says Oiamo. Some of those things include enforcing speed limits, limiting traffic within neighbourhoods, and regulating modified exhausts, the orientation of bedrooms, pavement type, tires, and so on. “You get into these seemingly unnecessarily detailed things, but like I said, it’s a million little things that add up to make a big difference,” he says.

Europe leads the way when it comes to noise monitoring and regulation. The Environmental Noise Directive (END) requires European Union member countries to publish up-to-date noise maps and noise management action plans. In France, Bruitparif is an organization that tracks noise in the region around Paris and provides regular monitoring, noise maps, and policy input. Germans have Ruhezeit, a legally entrenched quiet time that forbids excessive noise (including from laundry machines or vacuums) on Sundays and after 10 p.m. on weeknights.

In Canada, there are no national noise-prevention regulations. Noise is regulated through rarely enforced local or state bylaws, and most of the advocacy around the impacts is left to citizen groups.

Oiamo would certainly welcome meaningful policy change at whatever level, but more than that, he would like us to think about city soundscapes differently. “It’s not just about reducing noise but also recognizing that sound is a really important part of human experience. We care a lot about things looking nice. Why don’t we care about things sounding nice?”

Sound aesthetic is important for another reason besides our pleasure. It might lead to a more ethical relationship with our environment and the people around us. Jordan says, once we deal with harmful, excessive noise that causes physical and psychological damage, we might want to reconsider how we deal with the soundscapes we live and work in. He thinks it would make us better citizens and better humans. Roman philosopher Seneca advocated for a more relaxed approach to dealing with everyday noise: acceptance. Ideally, one would learn to ignore the noise rather than try to silence the world. It’s something to strive toward, Jordan says, but cheerfully admits that he is so far failing miserably to live up to Seneca’s ideal. Instead, he offers another way forward, one that dates back to antiquity.

He tells the story of acousmatics. Legend has it that Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras would make his students, acousmatics, listen to his lecture from behind a curtain, without seeing him. This would go on for years. The idea, says Jordan, was to force the students to really listen to his words with undivided attention.

“Telling people to be quiet is not a good thing,” he says. “Part of the charge to us as human beings in the world is to listen to other people, right? Especially if they are suffering. Especially if they are crying out to us for help. If our expectations are ‘I should not have to hear anything,’ and I can convince myself that the right way to live in the world is to live in this acoustically tailored environment, then I don’t have to hear all that stuff. . . . It becomes a part of the good life to essentially live in your own bubble.”

As the species responsible for much of the soundscape we and the others live in, the least we can do is listen.