Did the universe really begin with a Big Bang? And if so, is there evidence? Are there planets around other stars? Can they support life?

The 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics goes to three scientists who have provided deep insights into all of these questions.

James Peebles, an emeritus professor of physics at Princeton University, won half the prize for a body of work he completed since the 1960s, when he and a team of physicists at Princeton attempted to detect the remnant radiation of the dense, hot ball of gas at the beginning of the universe: the Bang Bang.

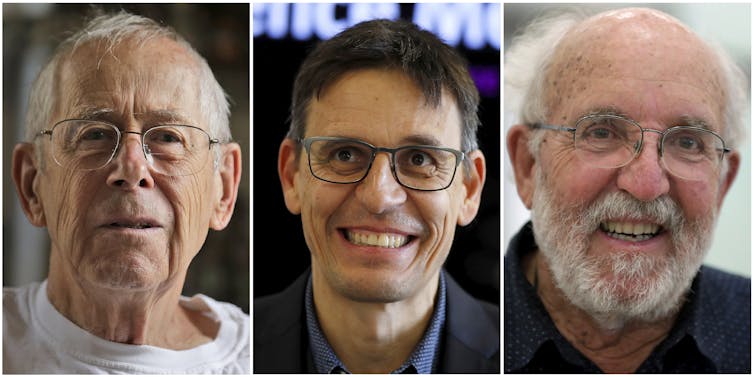

The other half went to Michel Mayor, an emeritus professor of physics from the University of Geneva, together with Didier Queloz, also a Swiss astrophysicist at the University of Geneva and the University of Cambridge. Both made breakthroughs with the discovery of the first planets orbiting other stars, also known as exoplanets, beyond our solar system.

I am an astrophysicist and was delighted to hear of this year’s Nobel recipients, who had a profound impact on scientists’ understanding of the universe. A lot of my own work on exploding stars is guided by theories describing the structure of the universe that James Peebles himself laid down.

In fact, one might say that Peebles, of all this year’s Nobel winners, is the biggest star of the real “Big Bang Theory.”

The real Big Bang Theory

As Peebles and his Princeton team rushed to complete their discovery in 1964, they were scooped by two young scientists at nearby Bell Labs, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson. The remaining radiation from the Big Bang was predicted to be microwave energy, in much the same form used by countertop ovens.

It was a serendipitous finding because Penzias and Wilson had constructed an antenna to detect this microwave radiation which was used in satellite communications. But they were mystified by a persistent source of noise in their measurements, like the fuzz of a radio tuned between stations.

Penzias and Wilson talked to Peebles and his colleagues and learned that this static they were hearing was the radiation left over from the Big Bang itself. Penzias and Wilson won the Nobel Prize in 1978 for their discovery, though Peebles and his team provided the crucial interpretation.

Peebles has also made decades of pivotal contributions to the study of the matter which pervades the cosmos but is invisible to telescopes, known as dark matter, and the equally mysterious energy of empty space, known as dark energy. He has done foundational work on the formation of galaxies, as well as to how the Big Bang gave rise to the first elements – hydrogen, helium, lithium – on the periodic table.

Finding planets beyond our solar system

For their Nobel Prize-winning work, Mayor and Queloz carried out a survey of nearby stars using a custom-built instrument. Using this instrument, they could detect the wobble of a star – a sign that it is being tugged by the gravity of an orbiting exoplanet.

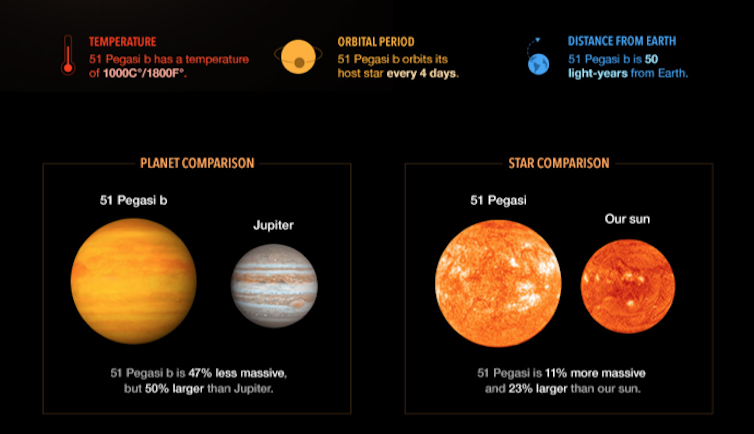

In 1995, in a landmark discovery published in the journal Nature, they found a star in the constellation Pegasus rapidly wobbling across the sky, in response to an unseen planet with half the mass of Jupiter. This exoplanet, dubbed 51 Pegasi b, orbits close to its central star, well within the orbit of Mercury in our own solar system, and completes one full orbit in just four days.

This surprising discovery of a “hot Jupiter,” quite unlike any planet in our own solar system, excited the astrophysical community and inspired many other research groups, including the Kepler space telescope team, to search for exoplanets.

These groups are using both the same wobble detection method as well as new methods, such as looking for light dips caused by exoplanets passing over nearby stars. Thanks to these research efforts, more than 4,000 exoplanets have now been discovered.

Robert T Fisher receives funding from NASA.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.