The COP16 biodiversity conference opened on October 21, 2024. The UN conference is an opportunity to highlight that biodiversity is crucial for ensuring a sustainable food system. However, it is directly threatened by climate change and its side effects, such as the emergence of parasites. These disruptions, which reduce crop productivity and increase harvest uncertainty, threaten global food security.

Finding solutions to save the viability of our crops is a priority. In this area, the wild relatives and varieties of currently cultivated plants offer a source of genetic diversity for coping with global changes. Indeed, for thousands of years, they have faced major environmental changes. Some wild species have thus contributed to the adaptation of cultivated plants to high altitudes and various climatic conditions.

If we intend to rely on wild relatives to ensure crop diversification, we must characterize their diversity and ability to respond to climate change. Conservation and development programmes for diversity in agrosystems have already been initiated for annual species, such as cereals. Perennial species, like fruit trees, however, remain too neglected, even as human activities threaten their wild relatives. It is high time to come to their rescue!

The limitations of large seed banks for protecting fruit trees

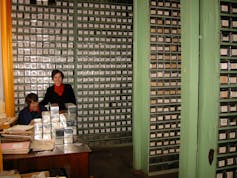

Faced with the collapse of biodiversity, nearly 2,000 seed banks have been created worldwide. The oldest, a pioneer in conserving the genetic diversity of plants, was established over 100 years ago in Saint Petersburg, Russia, at the Vavilov Institute, named after the scientist who initiated these collections. Another well-known example is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, set up in Norway in 2008. These “bunkers” are essential for preserving the genetic diversity of as many cultivated plant species and their wild relatives as possible. However, they are somewhat challenging to utilise in emergencies for certain plant species.

While new seeds can be obtained within a year for annual cereals, fruit trees can take years to reach sexual maturity and produce flowers and pollen, which presents a major challenge. Crossbreeding wild relatives with cultivated species, necessary to introduce favourable traits such as parasite resistance or climate adaptation, is lengthy. Leveraging the genetic heritage of fruit trees to address immediate challenges requires access to genetic material from mature trees, whose traits are already known and proven under specific environmental conditions. Therefore, genetic resource “bunkers,” while crucial for preserving diversity, are insufficient for fruit trees.

Our access to the genetic diversity of cultivated fruit trees and their wild relatives is currently limited, making it difficult to address the rapid changes occurring globally.

Conservation orchards: the “Noah’s arks” for fruit trees

Fruit trees have played a central role in human history through their economic and cultural value. The genetic exchanges between wild and cultivated fruit trees form the basis for the diversity of shape and taste in our fruits. The wild relatives of these cultivated fruit trees also have a significant role to play, as they have demonstrated resilience to parasites and climate change.

Conservation orchards, or living collections, for fruit trees serve as a means to preserve genetic diversity while making it available in case of emergencies to preempt threats associated with global changes. Unlike seed banks, these collections provide immediate access to the necessary materials (pollen and flowers) for crossbreeding in varietal improvement programmes, as well as for reforestation and the conservation of wild relatives in forests.

These conservation orchards also serve as open-air laboratories to study the response of fruit trees to climate conditions and parasite attacks, as well as the evolutionary and ecological processes that give rise to biodiversity. These spaces of genetic diversity, where different genotypes are planted over several years across a large area, also help limit the emergence of parasites by controlling their populations, thereby maintaining the delicate balance of biodiversity and ensuring dynamic agroecosystems. Finally, they act as venues for outreach and scientific mediation to raise awareness about fruit biodiversity in agroecosystems and ecosystems.

The “poor cousins” in conservation efforts

In France, living collections of cultivated fruit trees, housed by both research institutes and associations such as the “Croqueurs de Pommes” (munchers of apples) represent a valuable genetic heritage. In 2020, 168,400 hectares of orchards were recorded; however, wild fruit tree orchards are less documented and much rarer. This is regrettable, considering that these wild relatives are directly threatened by habitat fragmentation and gene flow from cultivated fruit trees in orchards, even though they are invaluable allies in addressing climate change.

However, there are some notable examples, such as the conservation orchards of wild olive trees at the French National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE) centre in Montpellier, the wild plum orchard in Lorraine, the wild apricot orchards at the INRAE centre in Bordeaux-Aquitaine, and various wild apple orchards across France including on the Saclay plateau [https://x.com/PommierVerger]. These orchards, established with the help of research institutes and local public initiatives, provide a unique opportunity to study the impact of parasite attacks and climate change on cultivated fruit trees and their wild relatives. Many more are being established across Europe, so it’s definitely something to keep an eye on!

Screening local fruit trees to help them adapt to global changes

Public involvement via citizen science is another way to gather information for the conservation of genetic diversity of fruit trees. Individuals can directly collect data from fruit trees near them – whether in their gardens, public parks or nearby fields – to advance research. These valuable contributions help ensure the monitoring of changes in flowering times related to climate change.

This aligns with initiatives launched through Pl@ntNet, an application that allows users to identify plant species using a simple photo, and Tela Botanica, which connects beginners with expert botanists to assist in launching collaborative projects.

By investing in the creation and maintenance of new orchards, strengthening collaboration among research institutes, associations and conservation organisations, and mobilising the public, one can play a role in preserving fruit biodiversity while enhancing fruit trees’ resilience to increasing environmental pressures.

Acknowledgments: Evelyne Leterme, Henri Fourey, Mathieu Brisson, Amandine Hansart, Alexandra Detrille, Mouhammad Noormohamed, the association Les Croqueurs de Pommes, and all project collaborators and participants as well as the general public.

Amandine Cornille (associate professor at New York University Abu Dhabi) has received funding from NYUAD, CNRS (ATIP-Avenir CNRS-Inserm), the European LEADER/FEDER program, the BNP Paribas “Climate and Biodiversity Initiative” Foundation, Institut Diversité Ecologie et Evolution du Vivant (IDEEV), Université Paris Saclay, CNRS, AgroParistech, INRAE, Center for interdisciplinary studies on biodiversity, agroecology, society and climate (C-BASC), CLand Convergence Institute and ANR.

Karine Alix has received funding from AgroParisTech, CNRS, INRAE, ANR and IDEEV.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)