Before renewables came along, coal-fired power stations pumped out electricity (and carbon emissions) 24 hours a day. But now, this type of “always on” baseload power is no longer necessary or commercially viable.

This is one of many reasons why the Coalition’s proposed nuclear strategy is flawed. Even if nuclear power was cheap, which it isn’t, it would have to be the least appropriate energy source going around.

Why? Because the world has changed. The greening of the electricity grid means we need far more flexibility. Solar and wind can do the heavy lifting, provided we have enough storage (batteries, pumped hydro and other technologies) and something we can quickly switch on and off to fill the gaps, such as gas or (eventually) hydrogen.

The only way to make nuclear power work in Australia is to switch off cheap renewable energy. Stop exporting electricity from your rooftop solar system. Forget feed-in tarrifs. The system has to call on baseload nuclear power first, or the plan makes no sense whatsoever. And to make space for nuclear in 10-15 years, you’d have to somehow make coal financially viable now.

Comparing the cost of electricity

The price we pay for electricity as customers is a function of the wholesale price retailers pay, to secure energy from generators, plus the cost of transporting it (transmission and distribution).

To compare the cost of nuclear power to other sources, we need to take a closer look at each generator’s capital and operating costs.

For capital costs, the market operator and most energy analysts turn to the CSIRO GenCost report. It finds conventional nuclear power stations cost 40% more to build than coal, 2.5 times more than onshore wind and 5 times more than large-scale solar.

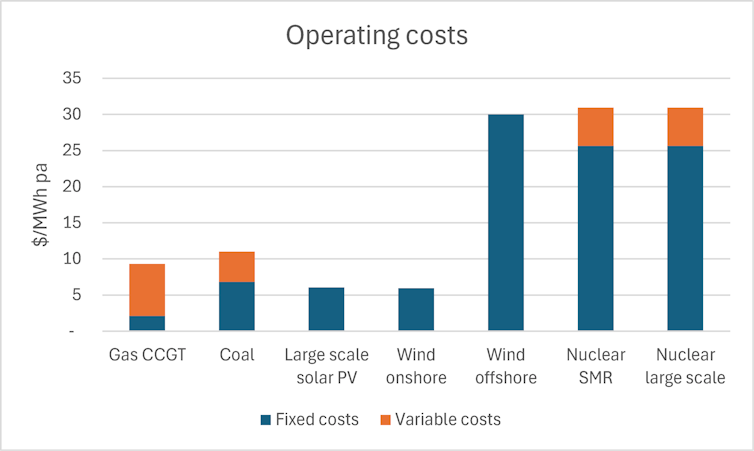

Operating costs reflect both fixed costs (such as maintenance) and variable costs (such as fuel). The less time the plant operates, the higher the capital and operating costs per megawatt hour (MWh) of output.

Both coal and nuclear can operate around 90% of the time at full capacity, while both wind and solar only operate at full capacity some of the time. So it’s best to compare annual operating costs on the basis of the actual energy generated in a year. Even on this basis it costs less to operate onshore wind and solar than coal or gas, mainly because there is no fuel cost.

Nuclear plants are incredibly complex and cost about five times more to maintain and manage than onshore wind and large scale solar. And that’s not including the high cost of decommissioning the plant, or treating and disposing of used fuel and wastes during its use.

South Australia offers a glimpse of the future

So far this analysis assumes all of the power plants operate at their optimum capacity. But the real world is not like that.

The market operator is required to supply electricity according to customer demand, which they do by dispatching the cheapest form available at the time.

This is onshore wind and solar, when available. However, network demand for electricity is also heavily influenced by what customers are doing to meet their own demand with rooftop solar.

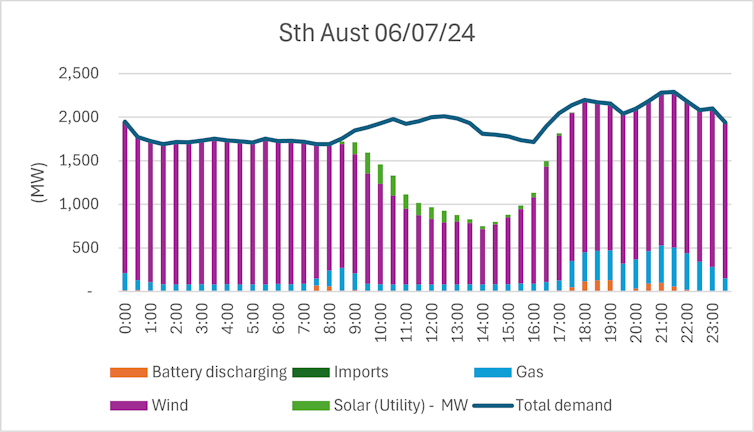

South Australia has lots of rooftop solar plus large-scale onshore wind and solar power plants. Just take a look at the hour-by-hour supply of electricity to SA customers on July 6 this year.

On this day in the middle of winter, private rooftop solar reduced demand by more than half in the middle of the day. Renewables (mainly wind) provided almost all the network electricity demand. A small amount of electricity was supplied by gas turbines (which are not baseload power generators) and batteries. No coal or gas generation was imported from other states.

About one third of SA homes have rooftop solar. As take-up inevitably grows, total network demand will continue to fall.

SA was the first state to see network demand fall below zero back in October 2021.

In the southwest of Western Australia the market operator is projecting network loads will become negative in coming years, something I predicted a decade ago.

As baseload generation is used less and less, it costs more and more per MWh and becomes less competitive and commercially viable. This is the main reason coal fired power stations are closing and baseload generation is becoming redundant.

SA is a predictor of the whole of Australia in coming years. If coal is not commercially viable into the future, then how can nuclear possibly be, when it is far more expensive?

Switching off solar and propping up coal

According to analysis by the Smart Energy Council the Coalition’s proposed seven nuclear reactors would only provide 3.7% of Australia’s electricity demand by 2050.

However, even if nuclear was to be a significant component of the mix by 2040 (under a very optimistic scenario), it wouldn’t be compatible with renewables already on rooftops and in the network.

That’s because nuclear power stations have very limited flexibility to power up, or power down. So if they are always on, something else has to be switched off. The only solution would be to “curtail” (switch off) cheap renewable energy, including exports from your rooftop solar.

For nuclear to be a significant energy source in future, Australia would have to start making more room for baseload power generation now. Existing coal-fired generators would have to be made financially viable so they can continue to operate until they’re eventually replaced by nuclear.

Meanwhile renewable generators and rooftop solar exports would have to be either disallowed from supplying the network or financially undermined – by government subsidies for coal and gas plants. The result of either would of course be higher costs and higher emissions.

The market operator’s Integrated System Plan for the National Electricity Market aligns with my analysis of the WA network. That is, the optimum energy solution, from both a cost and emissions perspective, is a combination of:

- renewable generation (mainly wind and solar)

- storage in the form of pumped hydro and batteries

- small amounts of gas, eventually replaced by hydrogen, to fill in the gaps.

There is neither room, nor need, for nuclear energy in Australia.

Bill Grace is an independent sustainability adviser, researcher and consultant. He is a research committee member with the Centre for Policy Development.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.