A little over 150 years ago, over 30,000 hand cut and mounted samples of Indian textiles were painstakingly organised into an album series to educate and inspire commercial and design industries in India and Britain. Its creator, John Forbes Watson, called them ‘trade museums’.

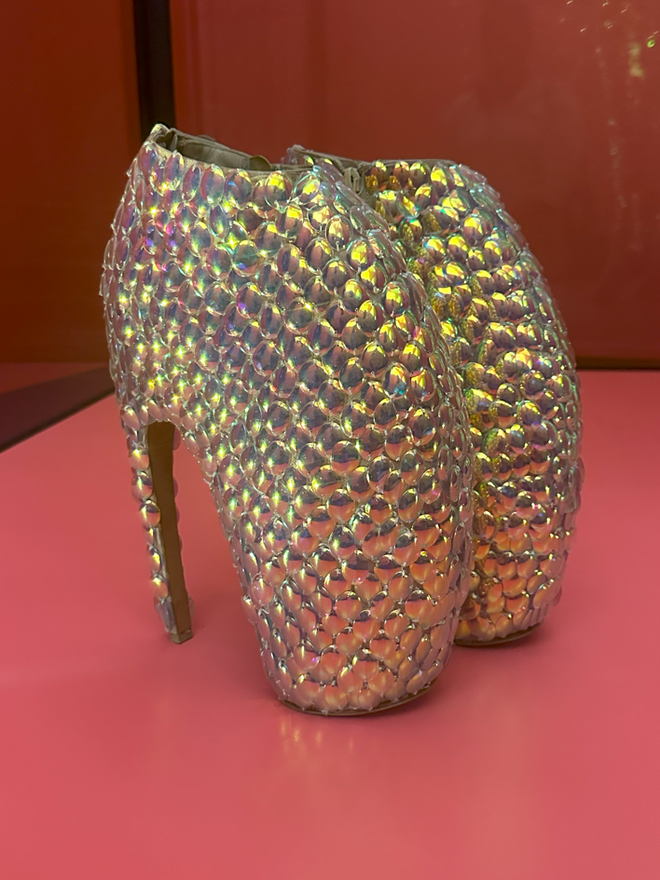

Watson would have been pleased to walk around the ‘India in Fashion’ exhibition at the newly-opened Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC) in Mumbai, which documents the country’s impact on global fashion in modern times. The exhibition starts off with a magnificent armadillo dress and a striking pair of shoes, notable for its unconventional shape and covered with scales of iridescent paillettes, designed by the late British designer Alexander McQueen for his Spring/Summer 2010 show, Plato’s Atlantis. The costume is juxtaposed against a large framed visual of a jewelled beetle, the Sternocera ruficornis — its shiny greenish-blue wings used frequently in exclusive embroidered textiles in India since the 15th century.

Captivated, British women in India had commissioned their gowns with this decorative element by the late 18th century and it soon spread across the costume world over the next century. From the iconic ‘Peacock Dress’ worn by Baroness Curzon at the Delhi Durbar in 1903 to celebrate the king’s coronation to paintings by American artist John Singer Sargent, these shiny green jewels captured the fashionable imagination.

This example of a quiet reverberation between India and the West is the leitmotif that British journalist and curator Hamish Bowles presents in this exhibition through around 140 costumes, carefully hand-picked and drawn from some of the biggest museums and formidable archives around the world. It is mounted in a nearly 50,000 square feet facility, with climate control capabilities making possible for the first time in India the hosting of international art exhibitions at this scale.

Intricate weaves and dramatic spaces

Presented as 10 segments — from 18th century Dutch costumes of chintz, a coveted colonial trade textile, and Indian craft inspired jewellery, to unseen haute couture archival pieces drawn from Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel, Dior and more — the curatorial prowess of bringing so many exhibits to Mumbai is admirable. It also demanded the onerous task of writing to multiple institutions, requesting these pieces of history, often up to four years ahead.

The emergence of the Ambani family at leading international museums, as patrons over the past two decades, has played a significant role in bringing vital pieces from museums such as the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Royal Ontario Museum and others. Costs for loans, wall-to-wall insurance, transport, conservation care, and a long list of other requirements are also part of the lending process.

In exhibition design director Patrick Kinmonth, Bowles found an able partner. The designer references the curator’s segmented narrative, picking up the scrutiny of fashion storytelling by referencing the architecture and vibrant colours from India and weaving it into the theme. He brings in a scale and grandeur of museum exhibition design that the country is not quite used to — visually connecting spaces and infusing drama.

That said, an oddity here and there disgruntles. Early in the walkthrough, after a pleasant ingestion of an 18th century block printed jama, one walks up a low-lit midnight blue ramp and is unexpectedly stunned with a blingy Bollywood trilogy of film costumes, all perched on disproportionate cylindrical bases and strangely lit with shimmering lights, almost like an afterthought. Costumes donned by Kajol, Kareena Kapoor Khan and Priyanka Chopra Jonas from popular Hindi cinema, and a mirrorwork Madhuri Dixit outfit a few steps later are an uncomfortable reminder that the patrons’ preferences must also be accommodated.

Bowles and Kinmonth tango smoothly in the sections ahead — references of the dreamy whiteness of a marble Mughal garden frame the Dhakai muslins and floral chintzes; a spectacular inverted stepwell theme showcases the YSL couture; and the Great Exhibition of London 1851, originally set in a magnificent glass Crystal Palace, is translated here as ribbed white skeletal arches that tower over softly-lit exhibits. There is a dramatic pacing of the fashion costumes and many hours of careful planning have been invested in bringing hundreds of details together to present an India story.

Also scattered throughout the exhibition are special commissions created by leading Indian designers such as Rahul Mishra, Ritu Kumar, and Anamika Khanna that respond to the thematic vintage craft, embroidery or silhouettes. Easily a favourite with visitors, they speak highly of the curatorial decision to extend patronage and bridge archival inspirations to contemporary times. These pieces created in 2022 -2023 take history and catapult it as a future vision and continue the story of fashion by creating new chapters.

Not everything works

However, for what was clearly intended as a blockbuster exhibition, several things fall short. The design in many spaces inhibits the visitor from seeing the costume up close, as some showcases move above and away from the eye level. And for a showcase that trumpets free entry to fashion and art students, the intent of instructional or educational material is poor.

The exhibition didactics are inefficient and a monumental opportunity to share and understand great fashion through textbook pedagogy of silhouette, form, pattern, cut and drapes has been lost. Some stunning examples of costume worthy of explanation, or at the very least sensible labels, are poorly lit and in absolute shadows.

The care and display of vintage textiles is a specialised craft, and whilst many costumes have been carefully installed by international lenders, there are other vintage costumes styled by celebrity sari drapers with safety pins, risking damage to the exquisite embroideries. In the long term, it might not be unwise for organisers to dip into the talented pool of textile conservators in our country so that rare books are not placed flat without much-needed supportive book rests or fragile textiles rested without quality rollers. On ground curatorial supervision is vital in such shows and, ultimately, something no amount of money can remedy.

Through ‘India in Fashion’ as its opening offering, NMACC clearly intends to impress Indian audiences, and succeeds in setting the bar high. One hopes that it can emerge as a cultural centre that truly brings world-class art to India and, in future, global audiences as well.

On till June 4; tickets on in.bookmyshow.com

The writer is an independent curator and the founder-director of Eka Archiving Services.