Looking for a telescope for the next night sky event? We recommend the Celestron StarSense Explorer DX 130AZ as the top pick for basic astrophotography in our best beginner's telescope guide.

The night sky tonight and on any clear night offers an ever-changing display of fascinating objects you can see, from stars and constellations to bright planets, the moon, and sometimes special events like meteor showers.

Observing the night sky can be done with no special equipment, although a sky map can be very useful, and a good telescope or binoculars will enhance some experiences and bring some otherwise invisible objects into view.

You can also use astronomy accessories to make your observing easier, and use our Satellite Tracker page powered by N2YO.com to find out when and how to see the International Space Station and other satellites. We also have a helpful guide on how you can see and track a Starlink satellite train.

You can also capture the night sky by using any of the best cameras for astrophotography, along with a selection of the best lenses for astrophotography.

Read on to find out what's up in the night sky tonight (planets visible now, moon phases, observing highlights this month) plus other resources (skywatching terms, night sky observing tips and further reading)

Related: The brightest planets in the night sky: How to see them (and when)

Monthly skywatching information is provided to Space.com by Chris Vaughan of Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu and Chris at @Astrogeoguy

Editor's note: If you have an amazing skywatching photo and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Calendar of observing highlights

Sunday, Feb. 1 - Full Snow Moon

February's full moon will occur on Sunday, Feb. 1 at 5:09 p.m. EST, 2:09 p.m. PST, or 22:09 GMT while it shines among the stars of Cancer. The indigenous Anishnaabe (Ojibwe and Chippewa) people of the Great Lakes region call the February full moon Namebini-giizis "Sucker Fish Moon" or Mikwa-giizis, the "Bear Moon". For them, it signifies a time to discover how to see beyond reality and to communicate through energy rather than sound. The Algonquin call it Wapicuummilcum, the "Ice in River is Gone" moon. The Cree of North America call it Kisipisim, "the Great Moon", a time when the animals remain hidden away and traps are empty. For Europeans, it is known as the Snow Moon or Hunger Moon. Full moons during the winter months climb as high at midnight as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows.

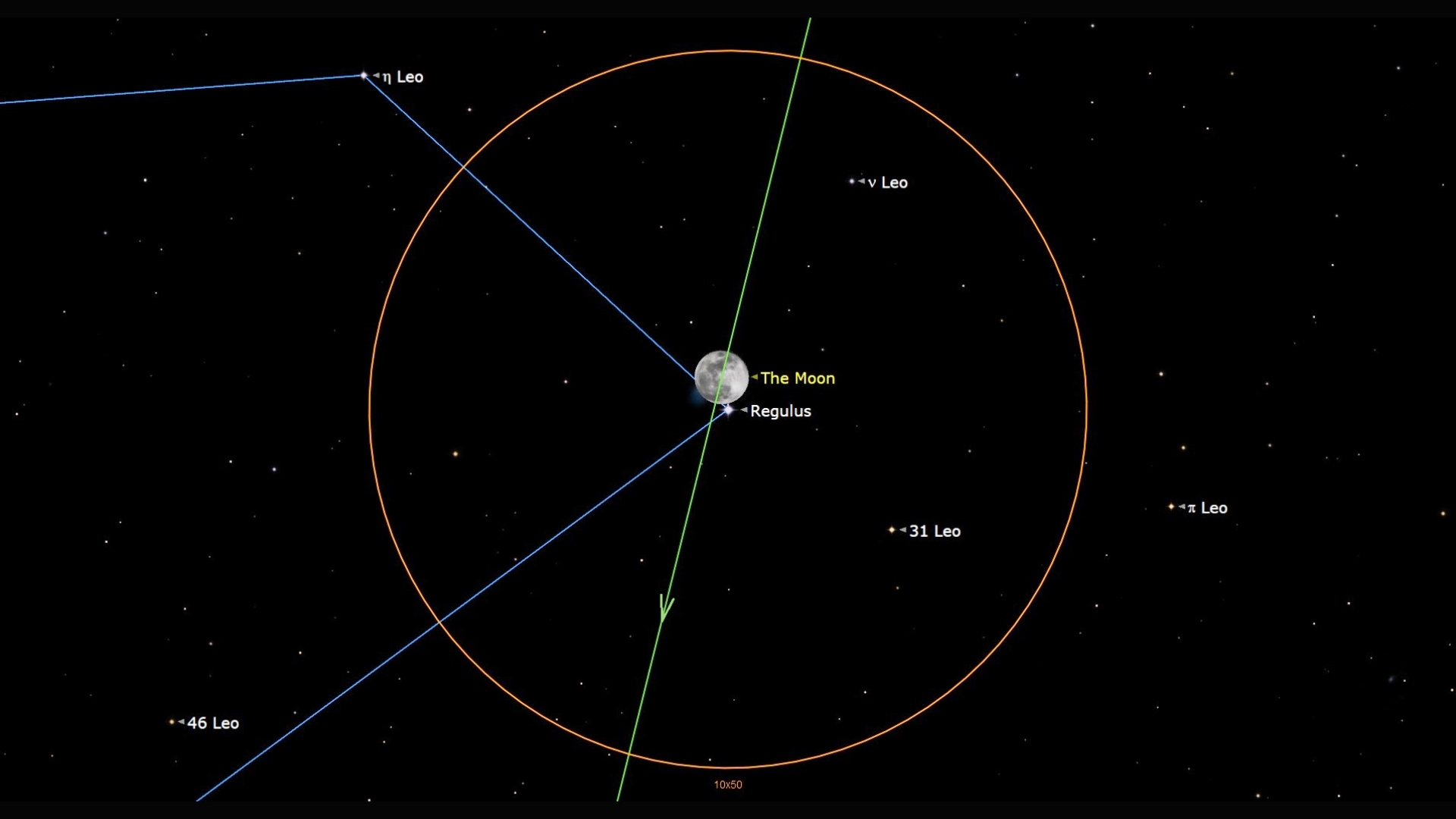

Monday, Feb. 2 - Bright moon covers the Lion's Heart

On Monday evening, Feb. 2, the brilliant, 98%-illuminated, waning gibbous moon will clear the rooftops in the east shortly after dusk and then cross the sky all night long. Binoculars and sharp eyes will reveal Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, the Lion, twinkling close to the moon all night long. Lucky observers within a zone extending from eastern North America and across the Atlantic Ocean to northwestern Africa will see the motion of the moon (green line) carry it in front of Regulus. In Toronto, Canada, the lit, bottom portion of the moon will cover Regulus at 8:48 p.m. Eastern Time. The star will reappear from behind the unlit top of the moon at 9:51 p.m. EST, nearest to the prominent crater Langrenus. In western Africa, the event will occur during the wee hours of Tuesday morning. Lunar occultations are perfectly safe to view with unaided eyes and through binoculars and telescopes (orange circle). The timing varies by location, so use an app like Starry Night or Sky Safari to preview the occultation where you live and be sure to start watching a few minutes ahead of each time.

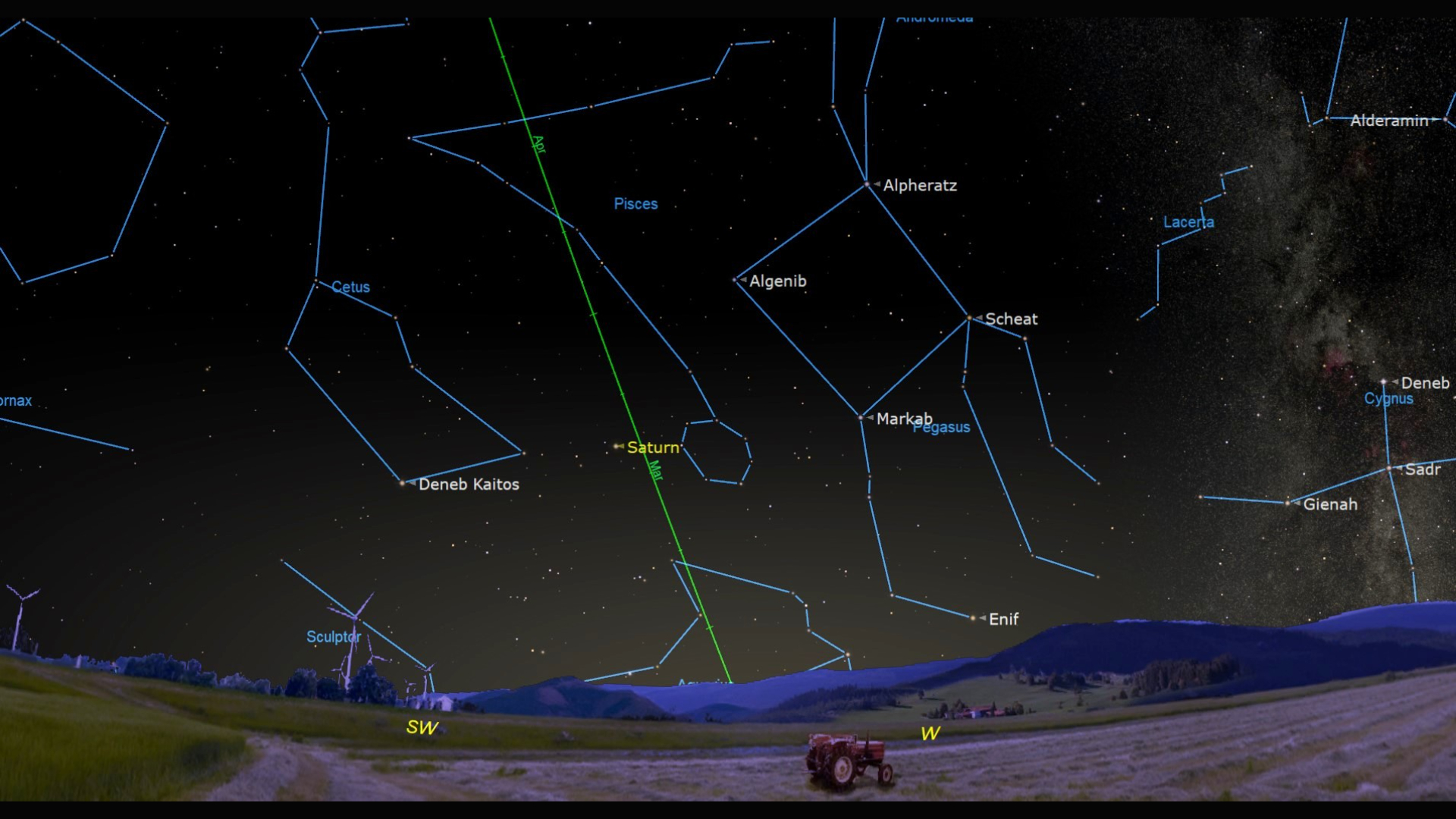

Tuesday, Feb. 3 - Evening zodiacal light (after dusk)

If you live in a mid-northern latitude location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot the Zodiacal Light from Tuesday, Feb. 3, until the new moon on Feb. 17. After the evening twilight has faded, you'll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic below the planet Saturn. That glow is the zodiacal light — sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don't confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year.

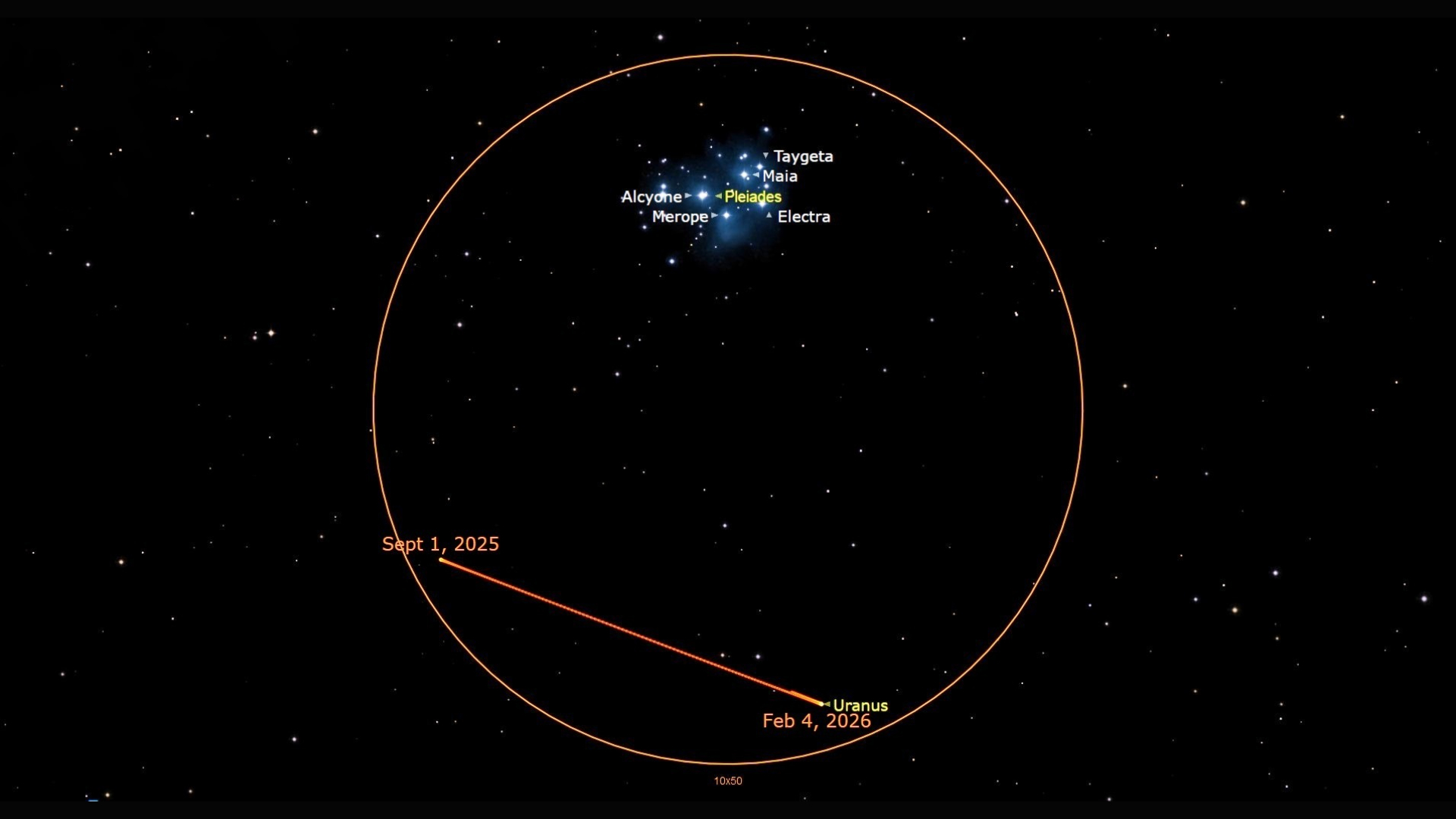

Wednesday, Feb. 4 - Uranus stops wandering west (evening)

On Wednesday, Feb. 4, the motion of the distant, blue-green planet Uranus through the background stars of western Taurus will slow to a stop — completing a westward retrograde loop that it began in early September. After tonight, the planet will start creeping eastward again. At magnitude +5.7, Uranus can be seen in binoculars and backyard telescopes, and even with unaided eyes under dark skies. In mid-evening, the planet's small, blue-green dot will be shining less than a palm's width below (or 5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the bright Pleiades star cluster, Messier 45. Place the pretty cluster at the top of your binoculars' field of view (orange circle) and Uranus will be the dull blue "star" on the opposite edge. Once you have identified Uranus, enlarge the planet with your telescope.

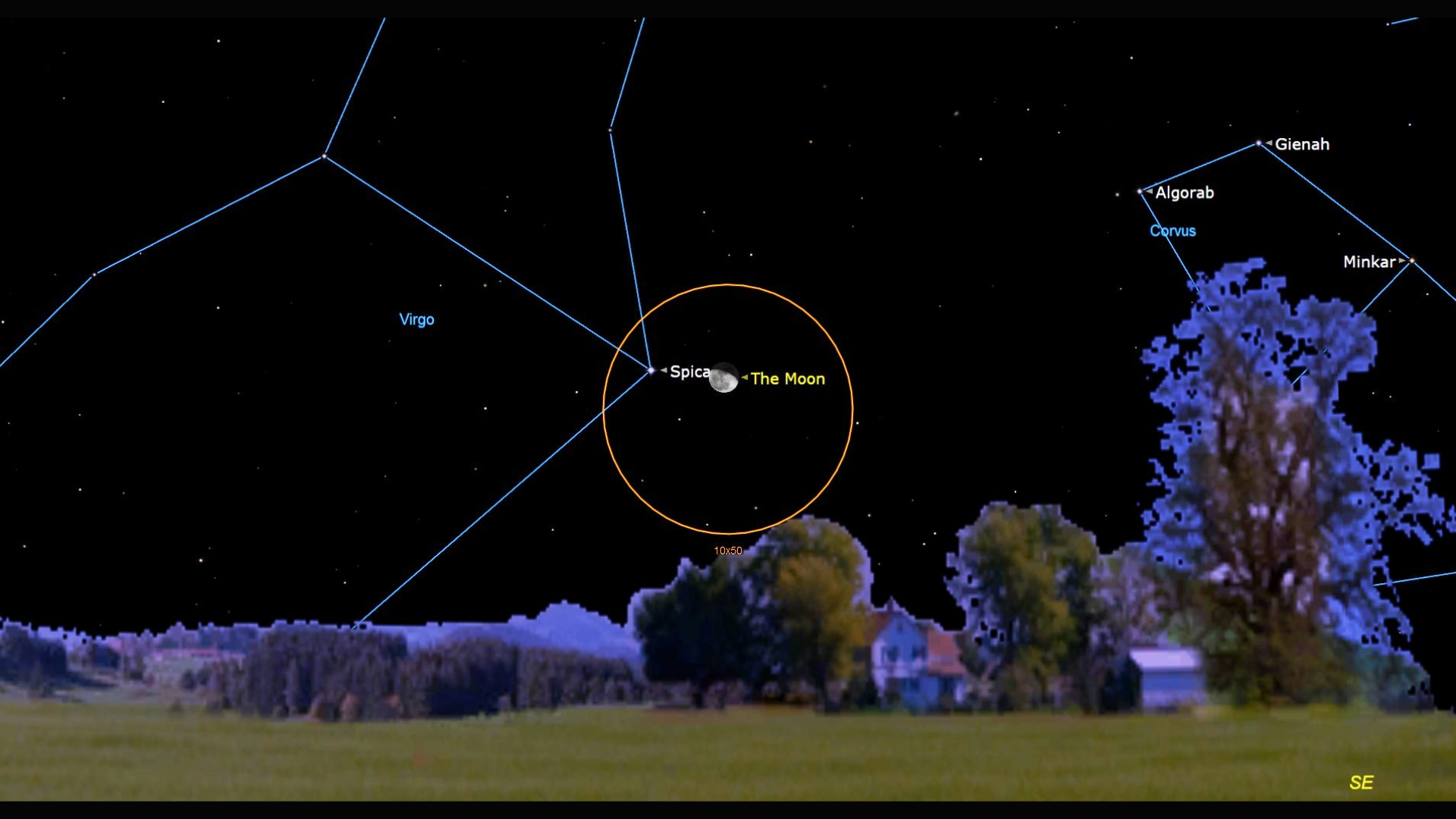

Friday, Feb. 6 - Moon shines with Spica (late night)

When the waning gibbous moon rises in late evening on Friday, Feb. 6 in the Americas, it will be shining just to the right (or celestial southwest) of Virgo's brightest star Spica. By sunrise on Saturday morning, the duo will post prettily partway up the southwestern sky. Meanwhile, the rotation of the sky will have shifted the moon below the star.

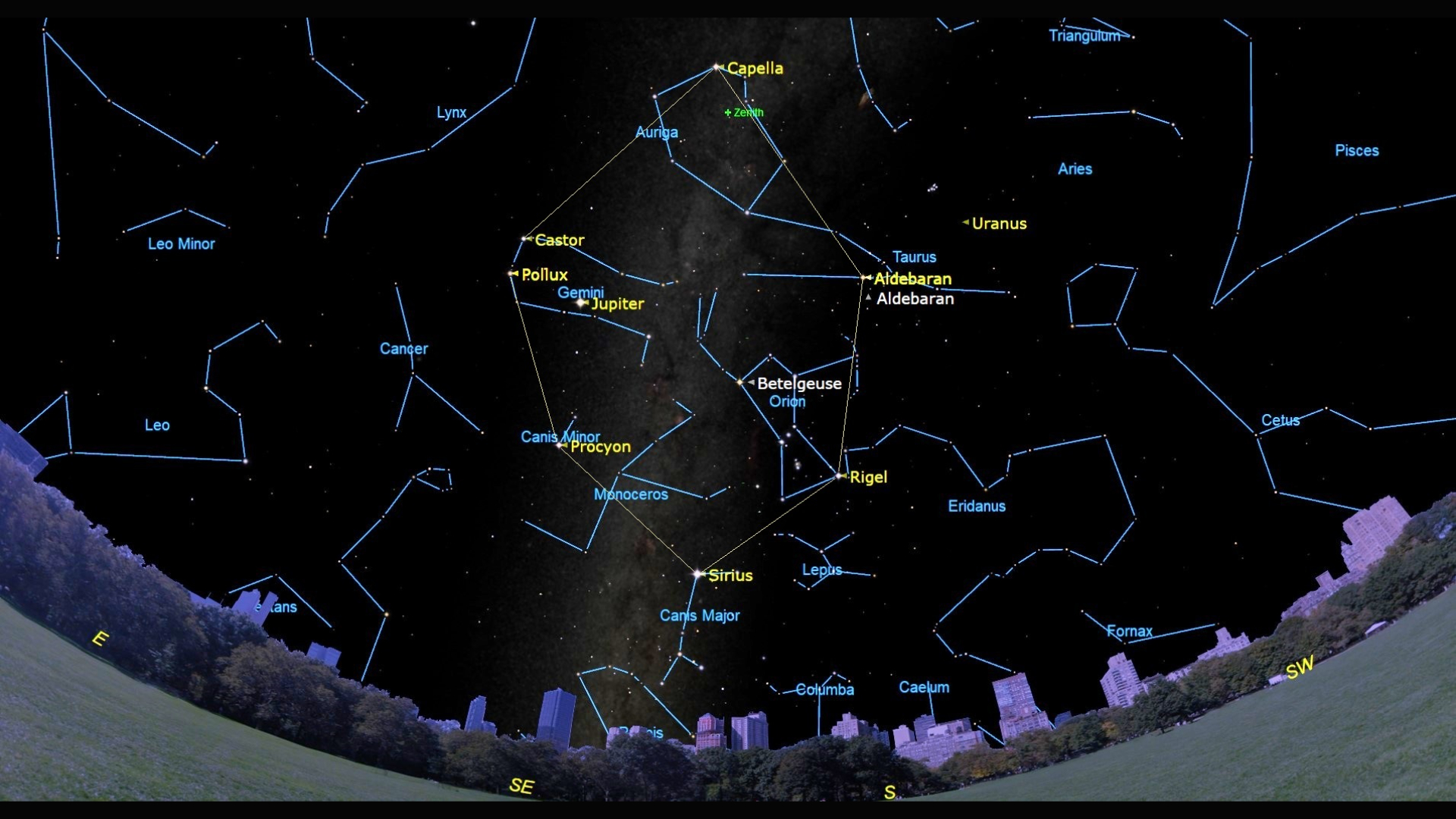

Sunday, Feb. 8 - The Winter Football (evening)

On February evenings, the southern sky hosts the Winter Football asterism, also known as the Winter Hexagon and Winter Circle. The huge pattern, which is composed of the brightest stars in the constellations of Canis Major, Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Gemini, and Canis Minor — specifically Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor and Pollux, and Procyon — covers a region of the southeastern sky after dusk that spans 65 degrees high by 45 degrees wide. Tilted to the east at dusk, the asterism will stand upright in the southern sky after mid-evening, with the Milky Way ascending vertically through it. This winter, the brilliant planet Jupiter will shine in Gemini near Pollux and Castor, turning the shape into a squashed diamond ring. The asterism is visible during the evening from mid-November to spring every year.

Monday, Feb. 9 - Third quarter moon

The moon will complete three-quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Monday, Feb. 9 at 7:43 a.m. EST, 4:43 a.m. PST, or 12:43 GMT. At its third (or last) quarter phase, the moon is half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. It will rise around midnight local time and then remain visible until it sets in the western daytime sky during the early afternoon. Third quarter moons are positioned ahead of the Earth in our trip around the sun. About 3½ hours later, Earth will occupy that same location in space. The week of dark, moonless evenings that follow this phase is ideal for observing the fainter objects in the night sky.

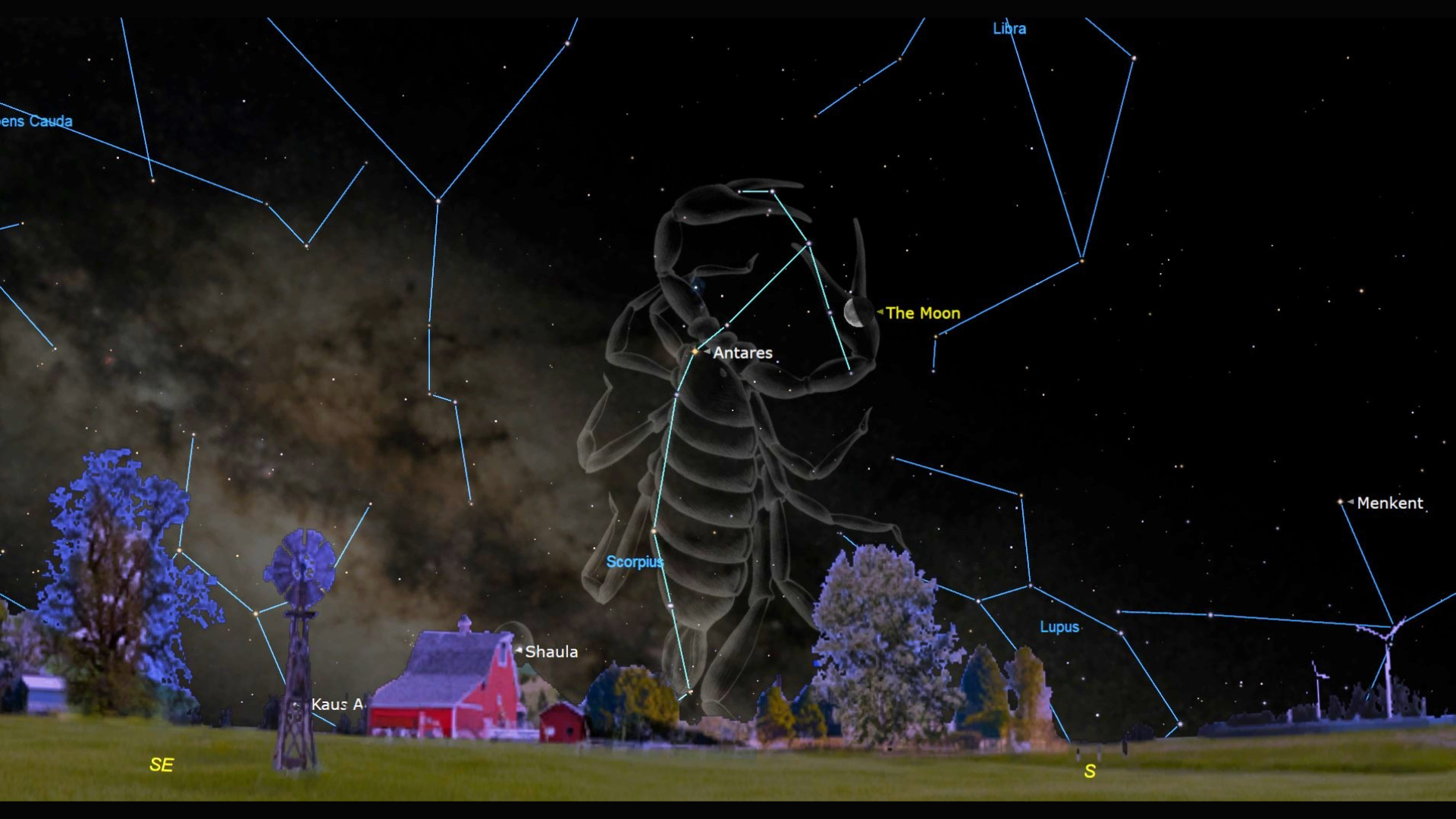

Tuesday, Feb. 10 - Crescent moon in the Scorpion's Claws (predawn)

Early risers on Tuesday morning, Feb. 10, in the Americas can look in the southern sky before sunrise to see the pretty sight of the waning crescent moon shining near the bottom of the up-down chain of stars that mark the claws of Scorpius. The bright reddish star Antares will twinkle off to the moon's left (or celestial east). That red giant star, which is located 550 light-years from our sun, marks the heart of the beast. The following morning, the moon will hop east to shine to Antares' left.

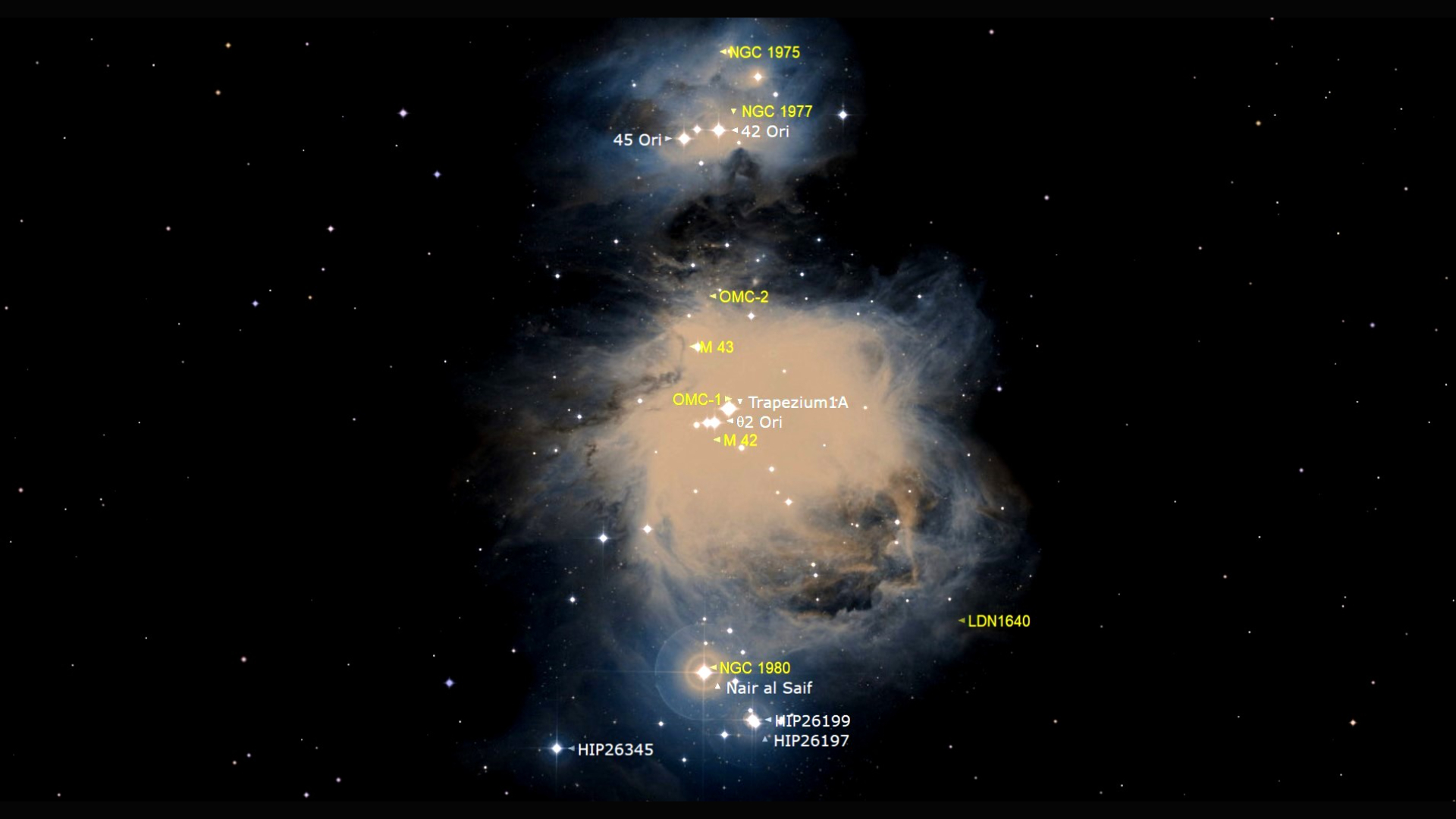

Friday, Feb. 13 - The spectacular Orion Nebula

The bright stars of mighty Orion, the Hunter, shine in the southern sky on mid-February evenings. The sword of Orion, which spans 1.5 by 1 degrees (about the width of your thumb held up at arm's length), descends from Orion's three-star belt. The patch of light in the middle of the sword is the spectacular and bright nebula known as the Orion Nebula or Messier 42 and NGC 1976.

While simple binoculars will reveal the fuzzy nature of this object, medium-to-large aperture telescopes (green circle) will show a complex pattern of veil-like gas and dark dust lanes and the Trapezium Cluster, a tight clump of young stars that formed inside the nebula. Adding an Oxygen-III or broadband nebula filter will reveal even more details. The nebula and the stars forming within it are approximately 1,350 light-years from the sun, in the Orion arm of our Milky Way galaxy.

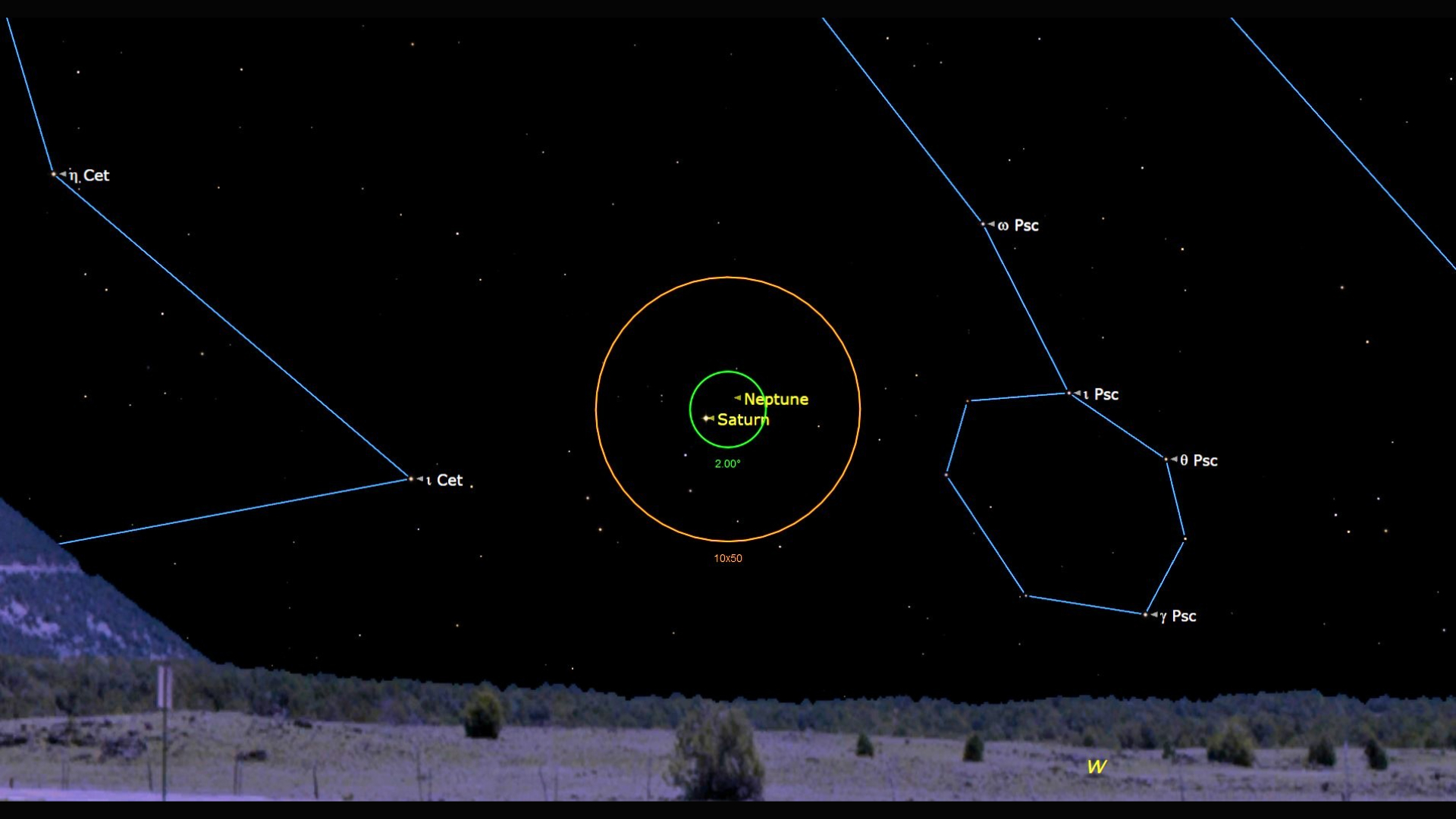

Monday, Feb. 16 - See Neptune near Saturn

For the better part of a year, the faint blue planet Neptune has been sharing the night sky with 650 times brighter Saturn. Their distance from one another has varied while each of them executed their own retrograde loops and orbital motion.

For about a week commencing on Monday, Feb. 16, Saturn will pass close enough to the remote planet for the pair to share the view in binoculars (orange circle) or any backyard telescope (green circle). In the sky, Neptune will be positioned less than a thumb's width to Saturn's right or 1.7 degrees to its celestial north and will shift a little lower each evening. Refractor (front lens) telescopes will mirror that arrangement and reflector (mirror in the bottom) telescopes will rotate Neptune to Saturn's lower left. At their minimum separation on Feb. 20, the two planets will be 0.8 degrees apart, or less than a finger's width.

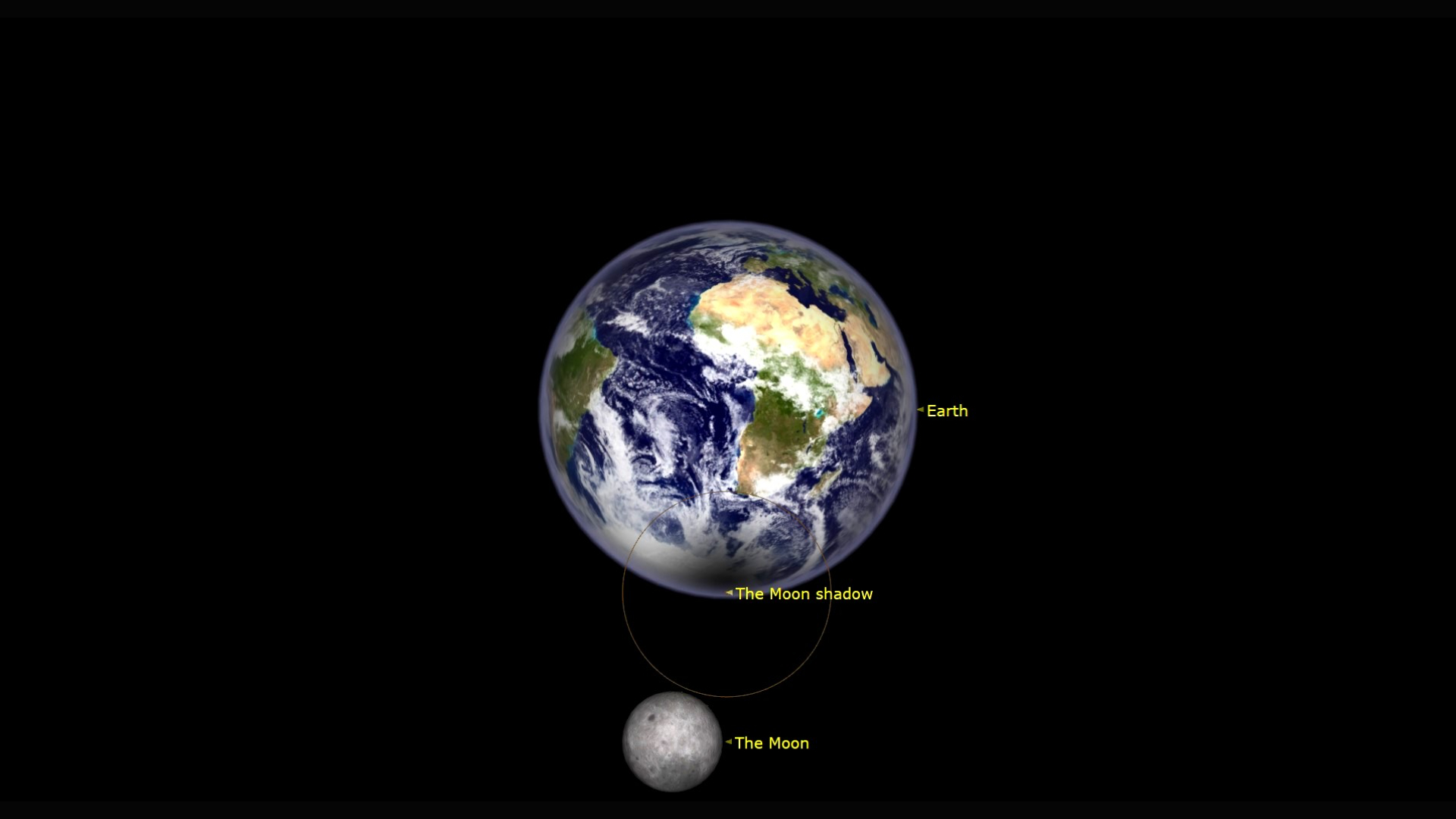

Tuesday, Feb. 17 - New moon annular solar eclipse

When the moon passes the sun in western Aquarius at new moon on Tuesday, Feb. 17 at 7:01 a.m. EST, 4:01 a.m. PST, or 12:01 GMT, it will generate a solar eclipse visible from the southern tip of South America, most of Antarctica, southeastern Africa, Madagascar, the Seychelles, and Mauritius. Since the moon is farther from the South Pole of the Earth, it will be too small to completely block the sun's disk, resulting in an annular, or "ring of fire", solar eclipse visible along a narrow track that sweeps across the Victoria Land portion of Antarctica and ends in the Southern Ocean south of western Australia. The partial eclipse will run from 10:51 GMT to 12:44 GMT, but the brief annular phase will only appear from 11:47 to 11:49 GMT. No portion of this eclipse can be viewed or photographed without proper solar filters. On the evenings following the new moon phase, Earth's planetary partner will return to shine in the western sky after sunset.

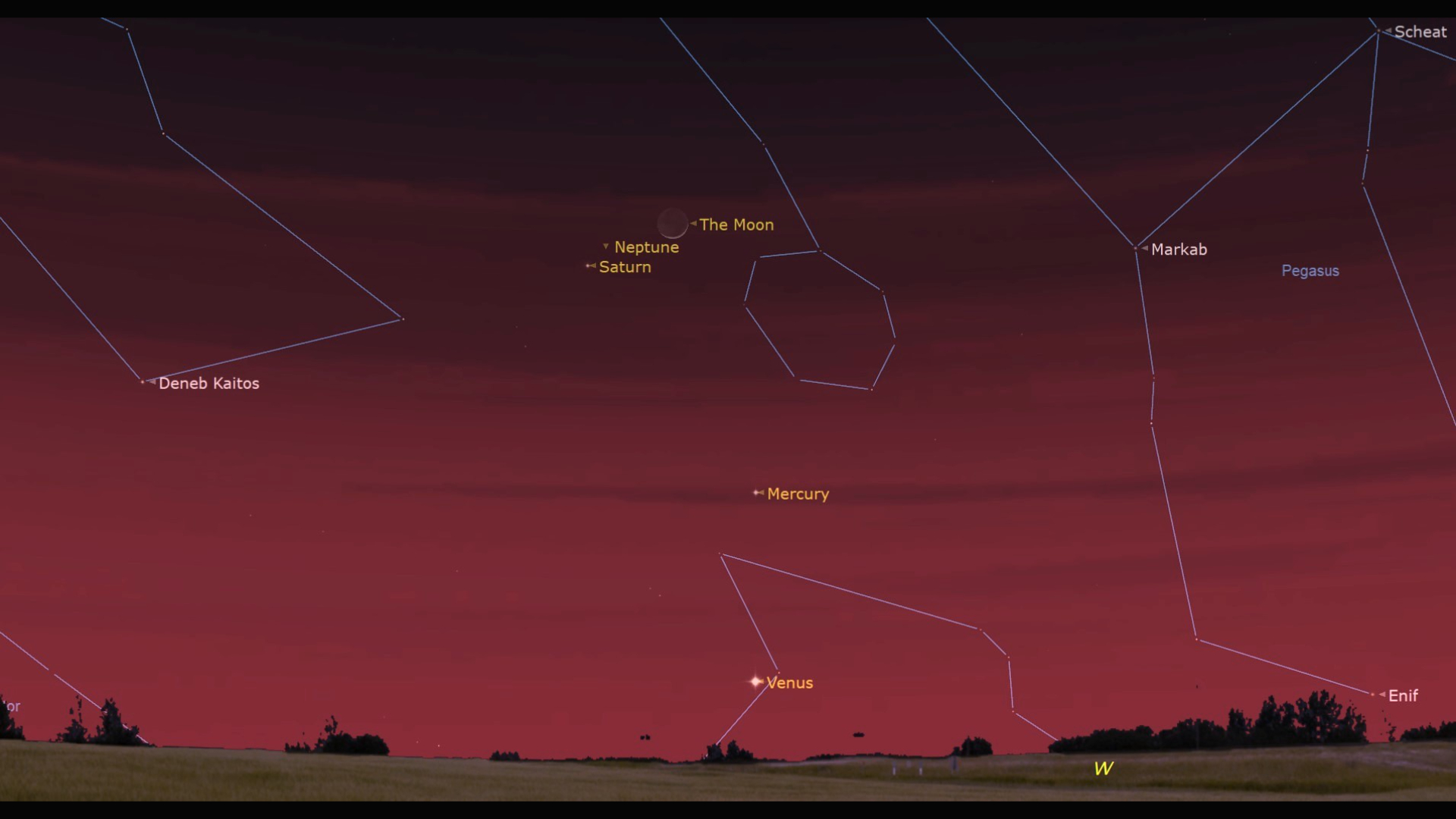

Wednesday, Feb. 18 - Sliver of moon poses with Mercury and Venus

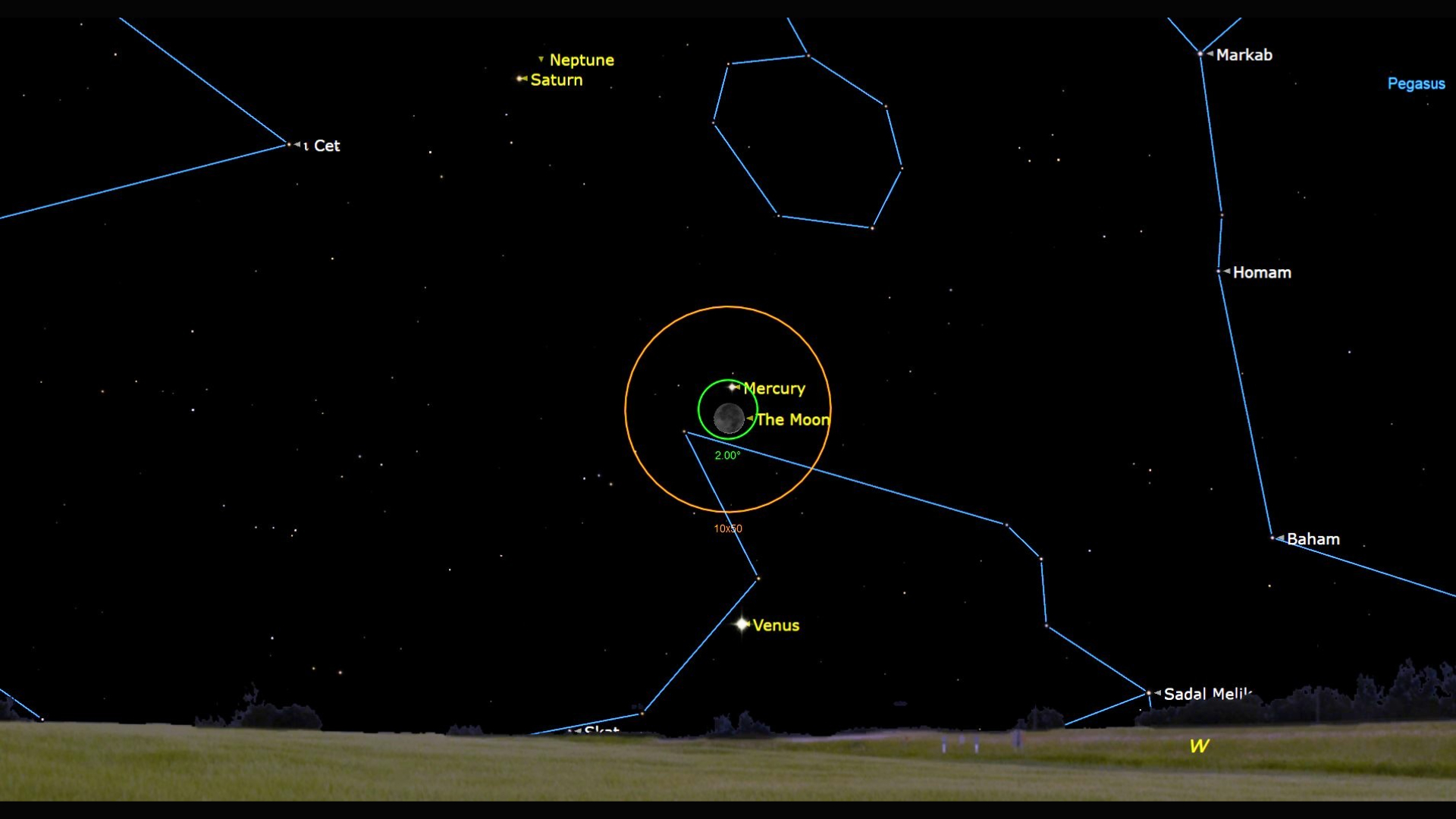

Above the western horizon for a brief time after sunset on Wednesday, Feb. 18, the 2%-illuminated, young crescent moon will join the inner planets Mercury and Venus. In Asia, the sliver of moon will be positioned about a finger's width to the right (or celestial north) of very bright Venus, close enough for them to share the view in a backyard telescope or binoculars. Less-brilliant Mercury will shine a generous palm's width above them. In the Americas, the moon will swap partners — appearing telescope-close (green circle) below Mercury while much brighter Venus gleams a generous palm's width below them. Meanwhile, observers located in a zone extending from the eastern coast of Australia and across New Zealand, southeastern Melanesia, parts of Polynesia, the Baha Peninsula, and most of Mexico and Central America can safely watch the moon occult Mercury after sunset. The timing varies by location, so use an app like Starry Night or Sky Safari to look up the occultation where you live and be sure to start watching a few minutes ahead of each time.

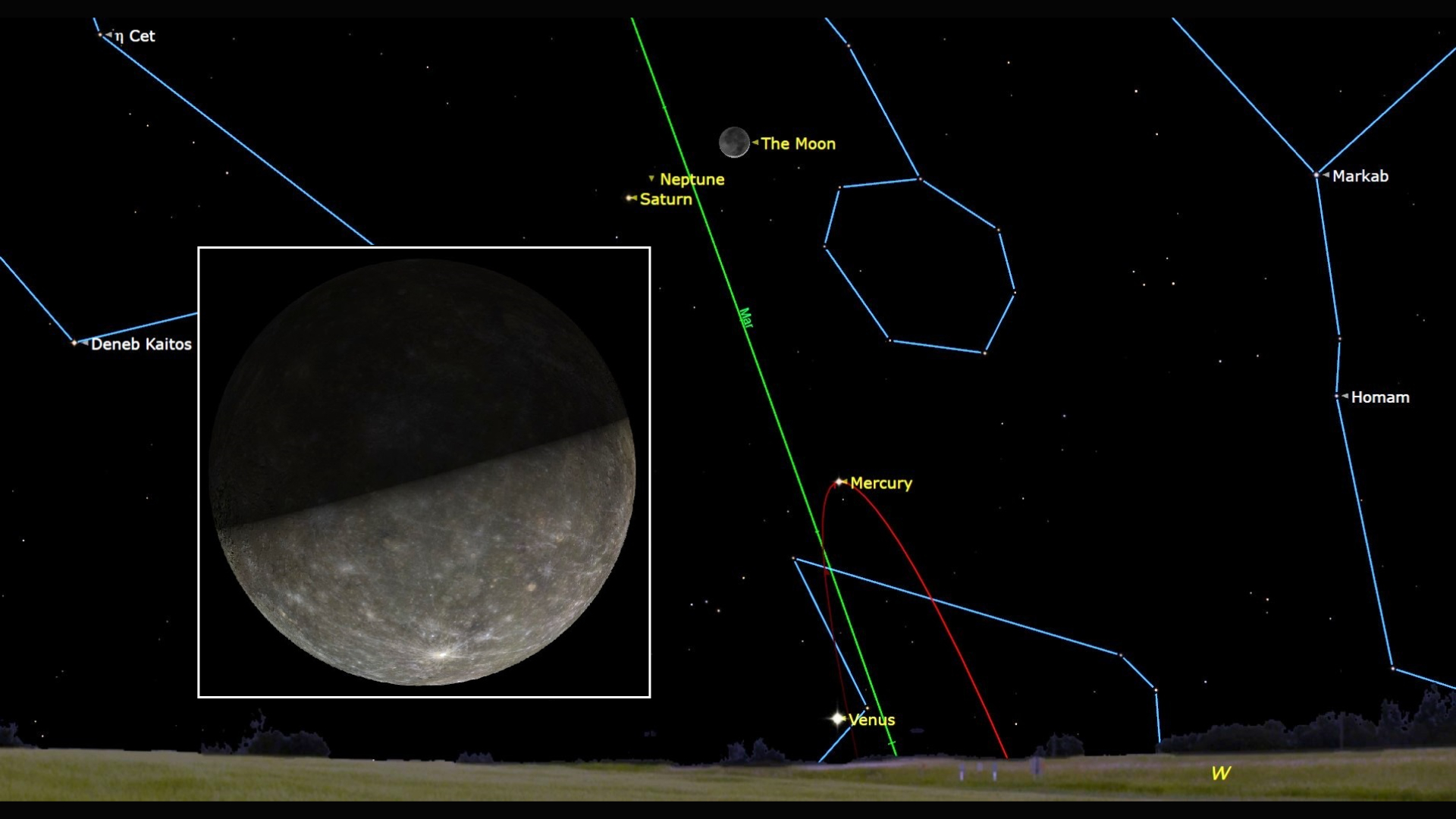

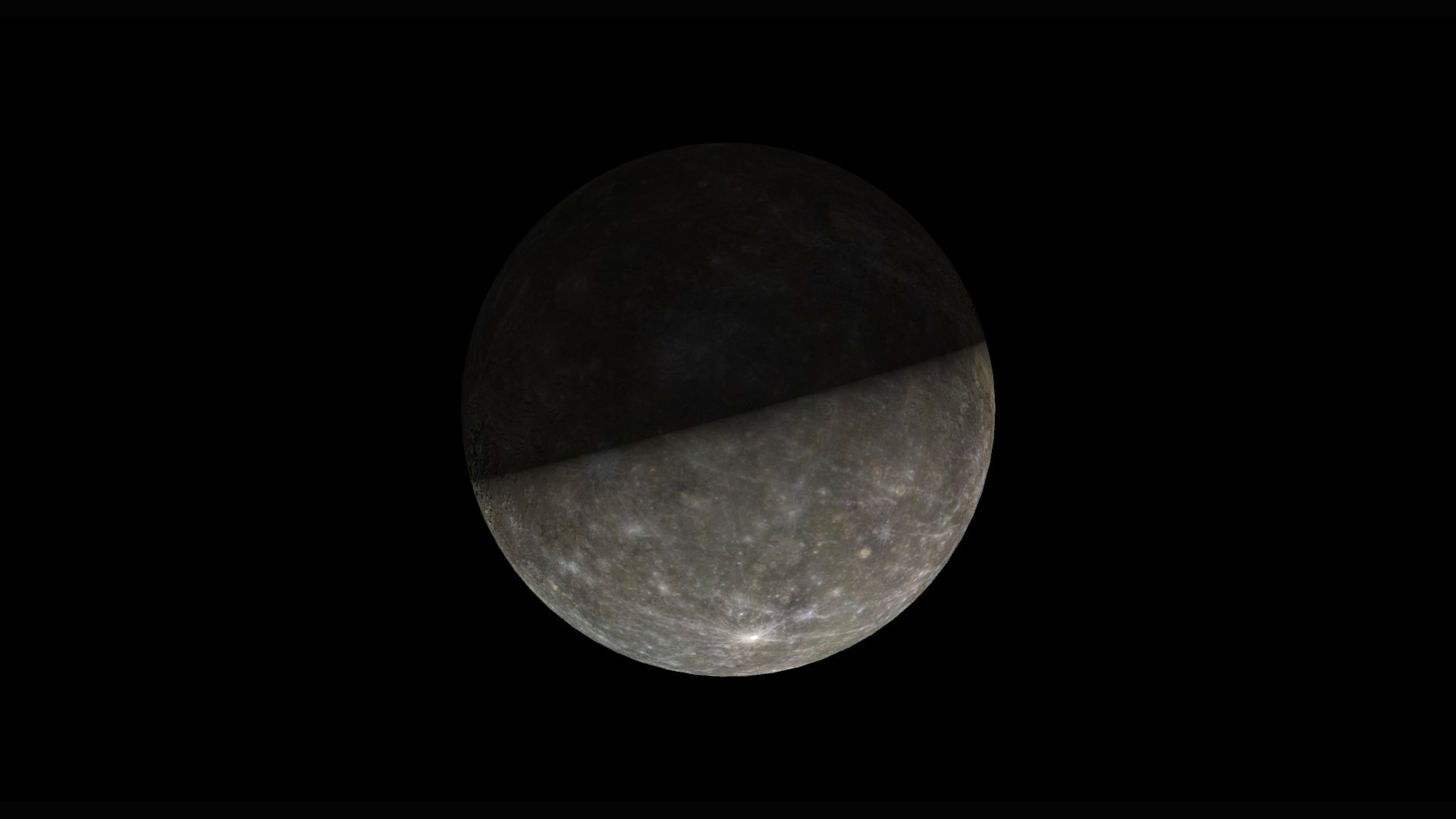

Thursday, Feb. 19 - Mercury at greatest eastern elongation

On Thursday evening, Feb. 19, in the Americas, Mercury (orbit shown in red) will reach its widest separation of 18 degrees east of the sun, and maximum visibility for the current brief apparition. With Mercury positioned above the evening ecliptic (green line) in the western sky, this appearance of the planet will be a very good one for Northern Hemisphere observers, but the planet will not be easily seen from the Southern Hemisphere.

The viewing window at mid-northern latitudes will last about an hour starting around 5:45 p.m. local time. Viewed in a telescope (inset), the planet will exhibit a waning, half-illuminated phase. Venus will gleam below (to the celestial west of) Mercury and the pretty crescent moon will shine beside Saturn and Neptune in the sky above Mercury.

Thursday, Feb. 19 - Earthshine moon joins a planet party

In the western sky after sunset on Thursday, Feb. 19, the young crescent moon will exhibit Earthshine, also known as the Ashen Glow and "the old moon in the new moon's arms". That's sunlight reflected off Earth and back onto the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon's Earth-facing hemisphere. The phenomenon appears for several days before and after each new moon. Since the Earthshine light has made an extra round trip from Earth to the moon and back, it is about 2.6 seconds "older" than the light we see from the lit crescent.

Brilliant Venus will shine just above the horizon with somewhat less-dazzling Mercury a palm's width above it. As the sky darkens more, Saturn's yellowish dot will appear a short distance to the left of the moon. Once the surrounding stars appear, use binoculars or a backyard telescope to see Neptune's faint blue speck less than a finger's width to the right of Saturn.

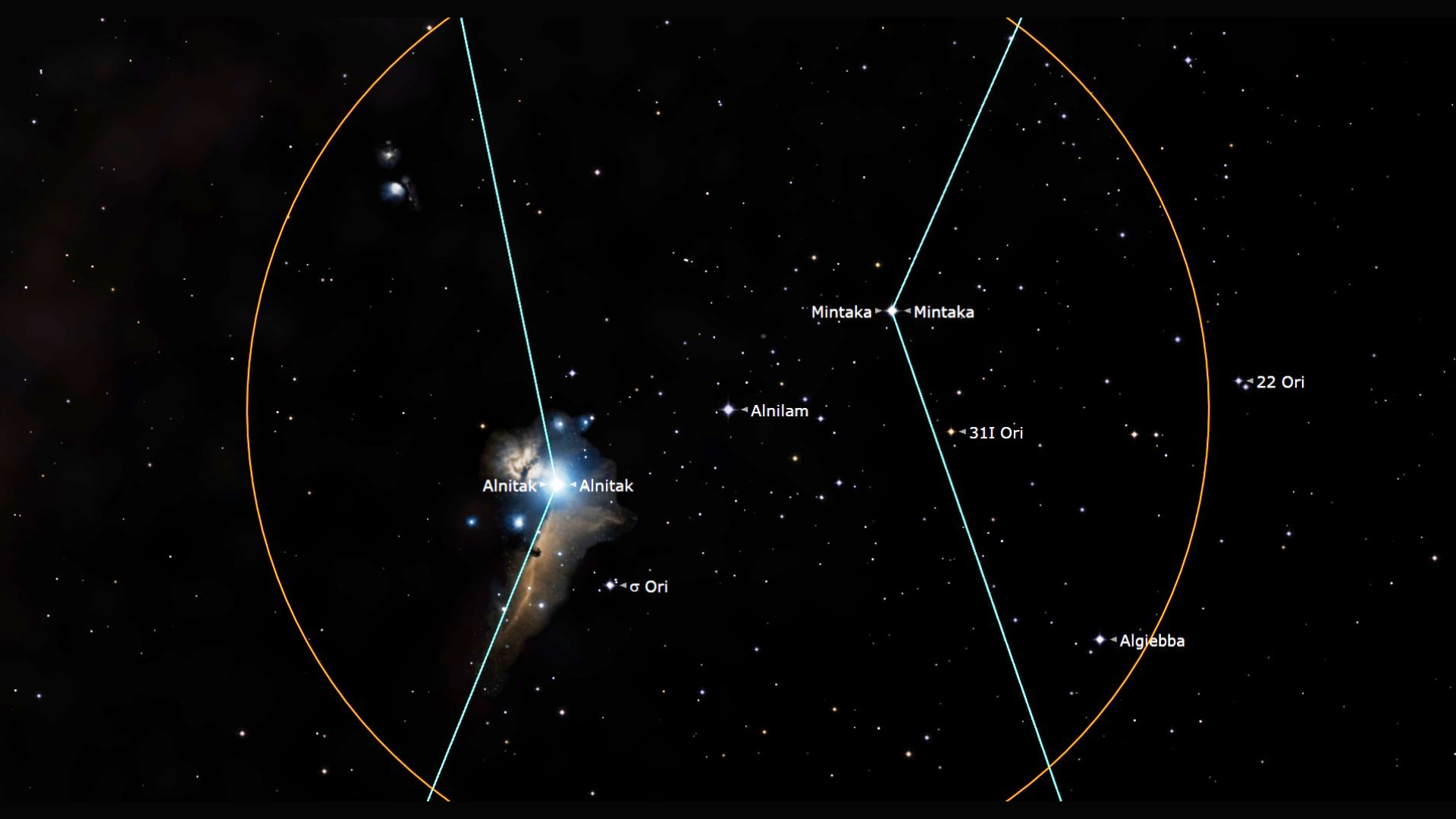

Saturday, Feb. 21 - The stars of Orion's Belt

The three stars that make up Orion's Belt are bright enough to tolerate some moonlight. The stars may look similar, but they are quite different under closer inspection. Magnitude 1.85 Alnitak (Zeta Orionis), the left-most (easterly) of the three, is bluer. In a telescope, Alnitak (Arabic for "the Girdle") is revealed to be a very tight double star. The nebulae surrounding Alnitak are a favorite target for photographers. The middle star Alnilam (Epsilon Orionis) is more than twice as far away as the other two. It is 1,976 light-years away from the sun. At the right-hand (western) end of the row, magnitude 2.4 Mintaka (Delta Orionis) is a more widely-spaced double star. Use binoculars (orange circle) to look for a large, upright, S-shaped asterism of dim stars in the space between Alnilam and Mintaka. Then switch to the medium-bright star sitting less than a finger's width below (or 0.8 degrees southwest of) Alnitak. That's Sigma Orionis, a beautiful little grouping of ten or more stars.

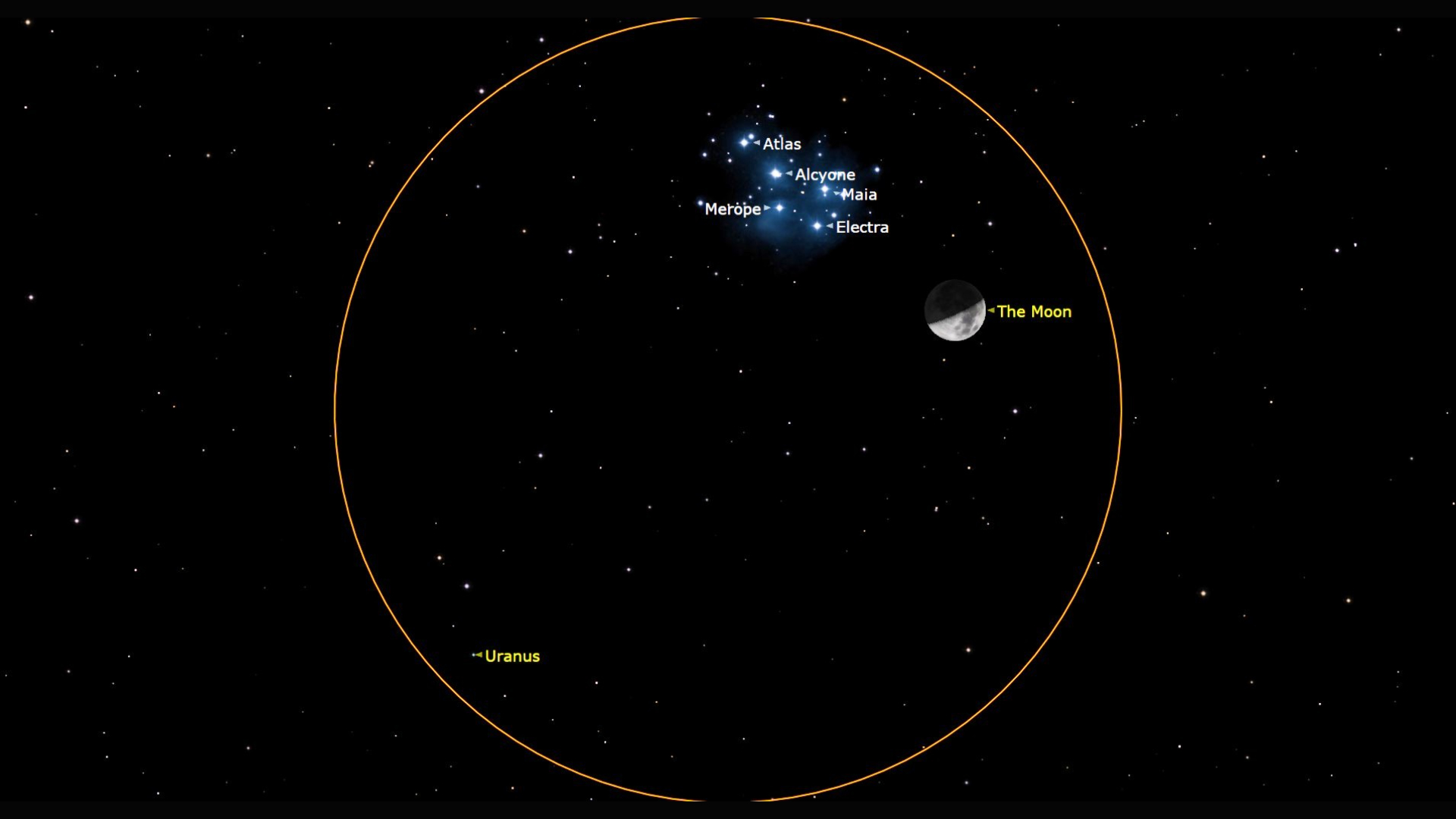

Monday, Feb. 23 - Half-moon skims the Pleiades

In the western sky on Monday evening, Feb. 23, in the Americas, the waxing half-moon will shine a short distance to the lower right (or celestial northwest) of the stars in the prominent Pleiades star cluster, which is also known as Messier 45, Subaru, and the Seven Sisters.

For those viewing the meet-up later or from more westerly time zones, the moon's eastward orbital motion will carry it through the outskirts of the cluster, occulting several of the stars. While the glare of the moon will hide the cluster's stars from your unaided eyes after dark, viewing the encounter during evening twilight, especially through binoculars (orange circle) or a backyard telescope, will allow you to see them better. The blue nebulosity around the Pleiades stars is only apparent with a very large telescope or a long exposure image when the moon is not close by. With the Pleiades positioned at the top of your binoculars' field of view, Uranus will be the bluish "star" at bottom left.

Tuesday, Feb. 24 - First quarter moon

The moon will complete the first quarter of its 29.53-day trip around Earth on Tuesday, Feb. 24, at 7:28 a.m. EST and 4:28 a.m. PST or 12:28 GMT. At first quarter, the moon's 90-degree angle from the sun causes us to see it half-illuminated on its eastern side among the faint stars of Pisces. First quarter moons always rise around midday and set around midnight, so they are also visible in the afternoon daytime sky. The evenings surrounding the first quarter are the best ones for seeing the lunar terrain when it is dramatically lit by low-angled sunlight, especially along the terminator, the pole-to-pole boundary that separates the moon's lit and dark hemispheres.

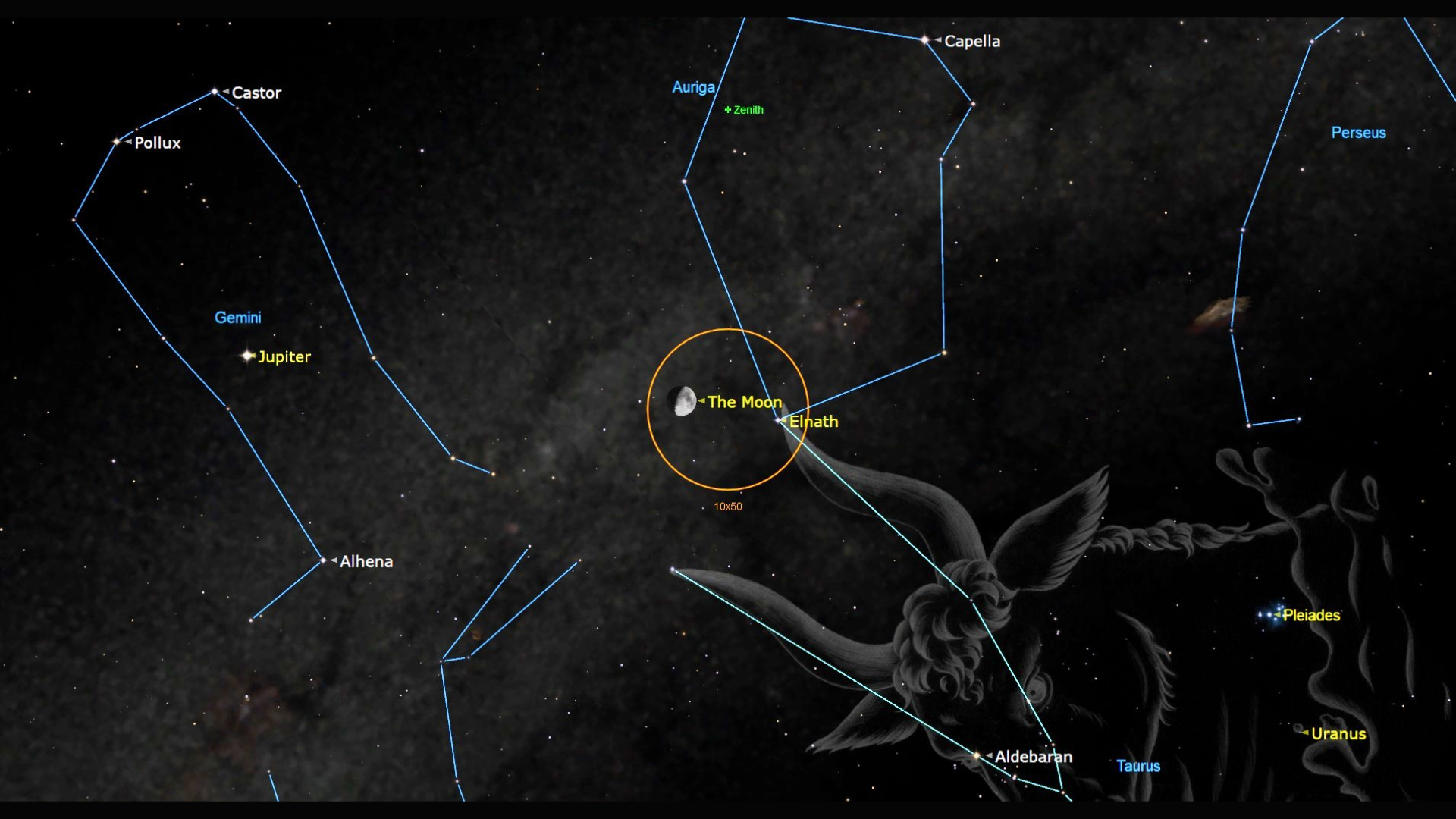

Wednesday, Feb. 25 - Moon near the bull's horn

On Wednesday, Feb. 25, the slightly gibbous moon will shine high in the eastern sky during late afternoon. As the sky darkens after sunset, the bright stars of the winter constellations will appear around it. The star that marks the northern horn tip of Taurus, known as Elnath and Beta Tauri, will be shining several finger widths to the moon's right (or celestial west), close enough to share the field of view of binoculars (orange circle) with the moon.

Hours earlier, observers in eastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula and within a zone that extends eastward across the Arabian Sea to the Maldives and Sri Lanka will be able to watch the moon occult Elnath in late evening. The timing varies by location, so use an app like Starry Night or Sky Safari to look up the occultation where you live and be sure to start watching a few minutes ahead of each time.

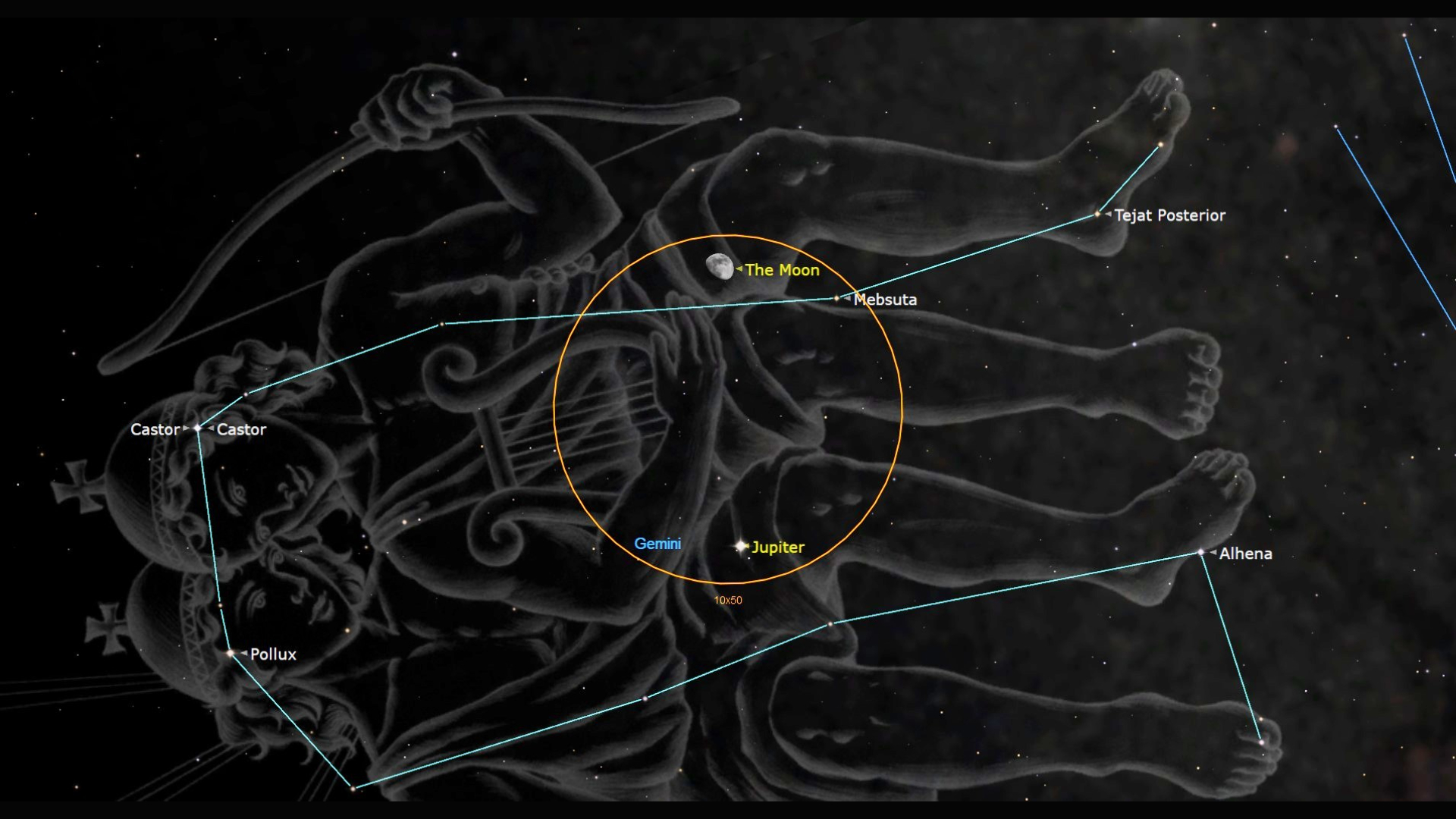

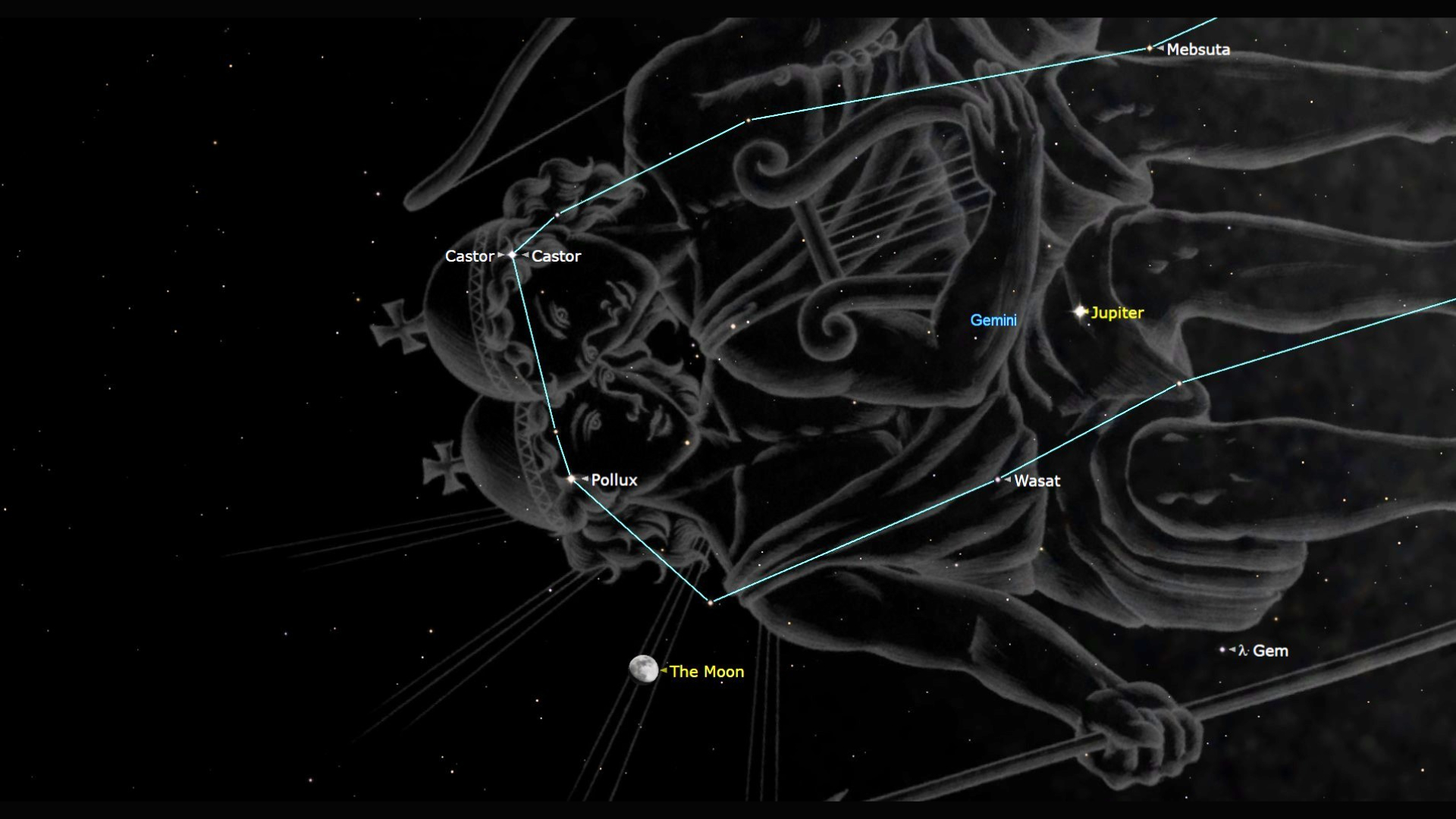

Thursday, Feb. 26 - Bright moon joins Jupiter in Gemini (evening)

At dusk on Thursday evening, Feb. 26, look to the east for the brilliant planet Jupiter shining a palm's width below (or celestial southeast) of the bright, waxing gibbous moon — cozy enough for them to share the view in binoculars (orange circle).

The duo will make a lovely photo opportunity when composed with some nice foreground scenery. As the moon and Jupiter climb higher, the bright stars of winter will appear around them, particularly Pollux and Castor, the bright twins of Gemini on their left (or celestial northeast). Both stars are part of the huge winter hexagon asterism. The moon and Jupiter will culminate due south around 8:30 p.m. local time and then set in the west in the wee hours of Friday morning. By then the moon will have moved closer to Jupiter and the diurnal rotation of the sky will have shifted the moon to Jupiter's upper right.

Friday, Feb. 27 - Moon aligns with Gemini's Twins (evening)

After 24 hours of motion, the moon's orbital motion will carry it lower in Gemini to form a crooked line with Gemini's brightest stars Pollux and Castor in the eastern sky after dusk on Friday, Feb. 27. The brilliant planet Jupiter will shine to the upper right of the trio, making a lovely visual and photo opportunity while they are carried across the sky all night long.

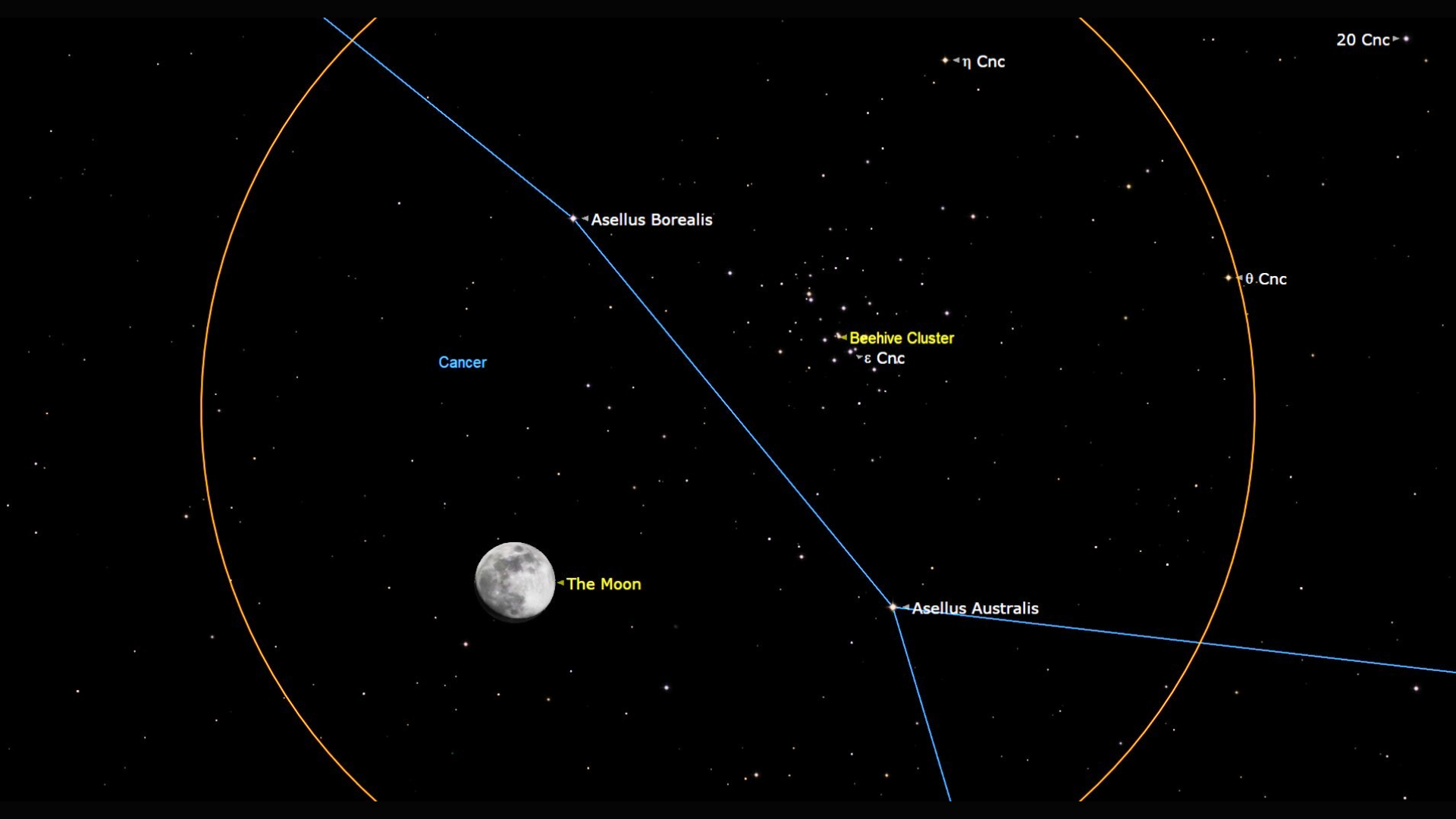

Saturday, Feb. 28 - Moon flees the Beehive (evening)

The bright, waxing gibbous moon will rise in the east during the afternoon on Saturday, Feb. 28. After the sky darkens, use binoculars (orange circle) to see the stars of the large open star cluster in Cancer known as the Beehive, Praesepe, and Messier 44 sprinkled several finger widths to the upper right (or celestial west) of the moon.

The moon will be slightly farther from the cluster for those viewing the scene later or in more westerly time zones. The bright moonlight will obscure the cluster's dimmer stars. To better see the "bees", which will be scattered across an area more than twice the size of the moon, hide the moon just beyond the lower left edge of the binoculars' field of view.

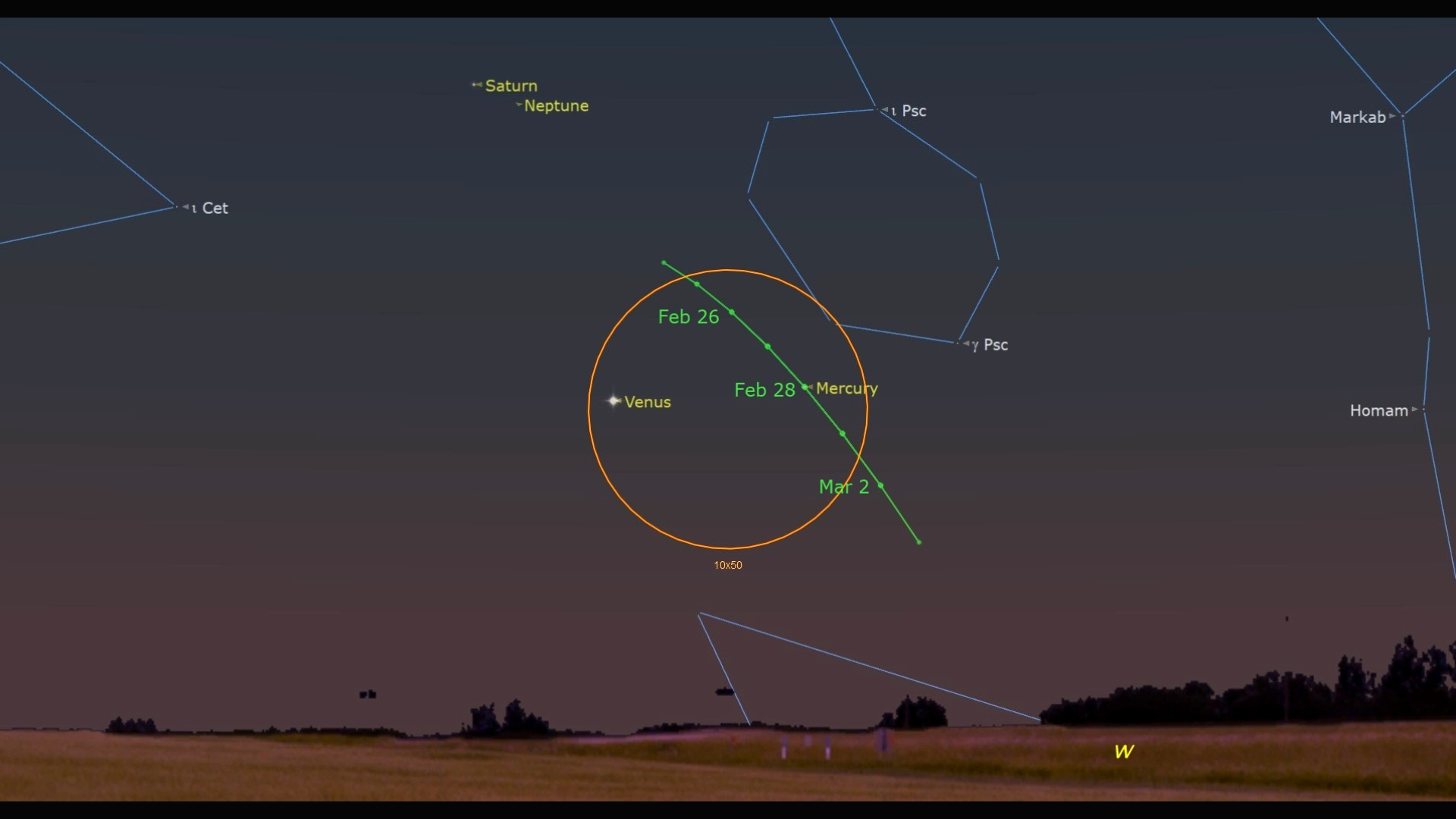

Saturday, Feb. 28 - Sunbound Mercury passes Venus

If you can spot the brilliant planet Venus shining above the western horizon after sunset on Saturday, Feb. 28, look for far fainter Mercury sitting less than a palm's width to Venus' right (or 4.8 degrees to its celestial NNW). That's close enough for them to share the view in binoculars (orange circle). Mercury's swing sunward (green path) will drop it past Venus for several days centered on Saturday.

Visible planets

Mercury

As February opens, Mercury will commence its best, albeit brief, evening apparition of 2026 for Northern Hemisphere observers, but it will not be observable from mid-Southern latitudes.

The innermost planet will emerge out of the western twilight during the first week of February and then climb to its maximum eastern elongation 18° from the sun on Feb. 19 while at the perihelion of its orbit. Mercury will shine brighter than magnitude 0.0 until Feb. 22, and then it will fade rapidly thereafter as it zooms toward inferior conjunction with the sun on March 7.

Telescope views of Mercury will show an apparent disk size that swells from 5 to 9.5 arc-seconds while waning in phase from 96% on Feb. 1 to only 11%-illuminated on Feb. 28. Far brighter Venus will climb in the west with Mercury, but it will remain lower than Mercury until the closing days of the month. The extremely thin young crescent moon will shine close to Mercury on Feb. 18, occulting it for observers located in a zone extending from the eastern coast of Australia and across New Zealand, southeastern Melanesia, parts of Polynesia, the Baha Peninsula, and most of Mexico and Central America.

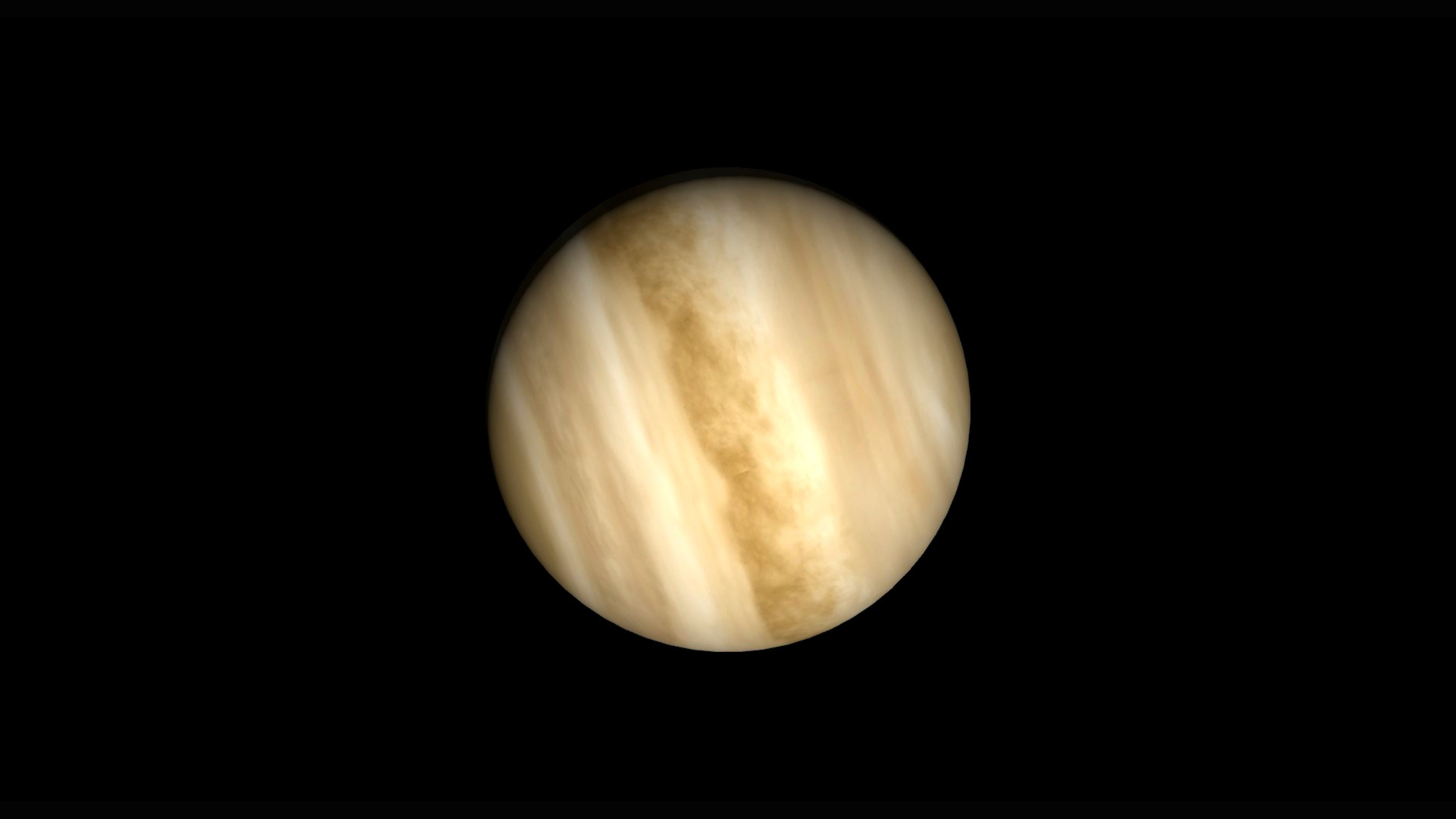

Venus

Brilliant, magnitude -3.9 Venus will commence a lengthy evening apparition as the "Evening Star" once it becomes visible against the western twilight after sunset in the first week of the month. In a telescope, Venus will display a nearly fully illuminated disk spanning 9.9 arc-seconds. Much less bright Mercury will shine above Venus until Feb. 18, when they will be joined by the 1.5-day-old young crescent moon. While Mercury descends sunward at month's end, it will pass several finger widths to Venus' right (or 4.5° to its celestial north) on Feb. 27.

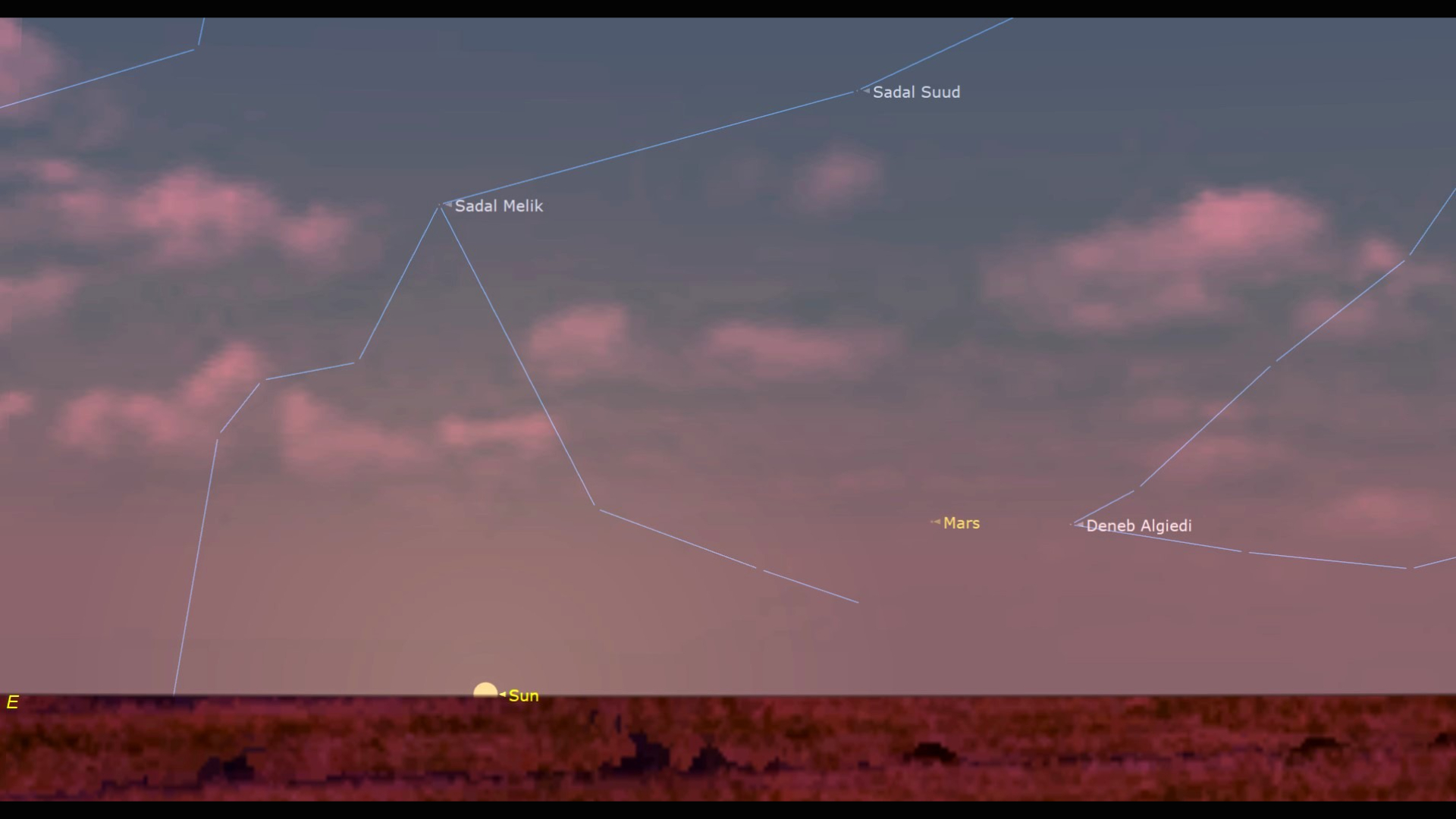

Mars

Following its solar conjunction on Jan. 9, Mars will remain hidden within the sun's glare in the eastern morning sky from northern latitudes, but it will gradually become visible for tropical and Southern Hemisphere observers as its angle from the sun doubles to 12° over the month. Mars' position on the far side of the solar system from Earth will keep the magnitude 1.17 planet from displaying any surface details in a backyard telescope until later this year.

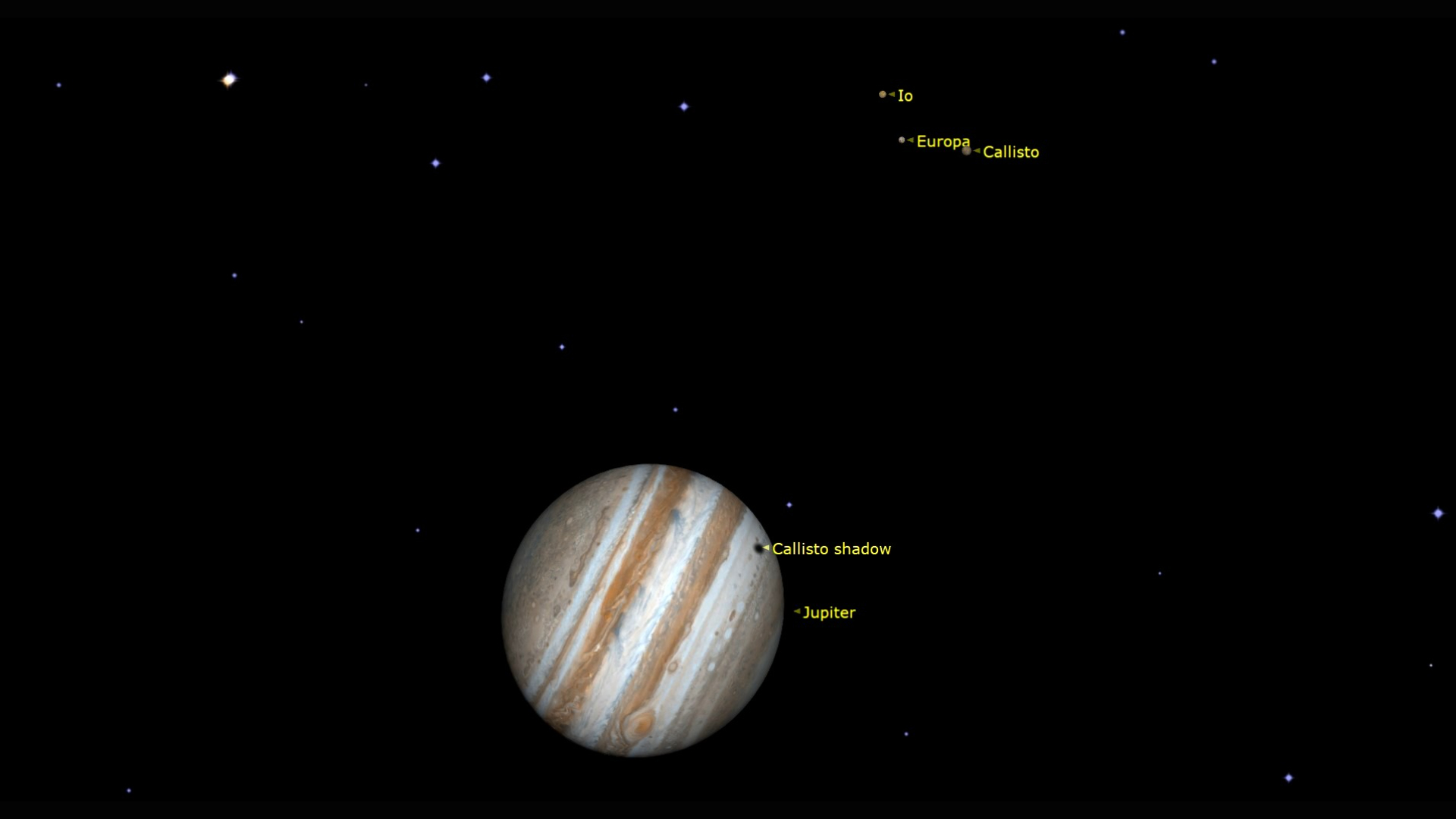

Jupiter

The extremely bright, white planet Jupiter will be well-placed for observing all night long during February, appearing in the east at sunset, culminating high in the southern sky during late evening, and then sinking in the west before dawn. The gas giant's westerly motion through central Gemini will slow as it prepares to complete a retrograde loop on March 11, all the while serving as an extra corner in the giant Winter Hexagon asterism near Castor and Pollux. Still fresh from opposition on January 10, Jupiter will gleam around magnitude -2.5 all month long. Binoculars will reveal Jupiter's four large Galilean moons flanking the planet on any clear night, and views of Jupiter in a backyard telescope will show the equatorial zones and belts on its generous 44.4 arc-seconds-wide disk. Better quality optics will reveal the Great Red Spot on every 2nd or 3rd night and the round, black shadows that Jupiter's Galilean satellites cast upon the planet's disk from time to time. The waxing gibbous moon will shine near Jupiter on Feb. 26 and 27.

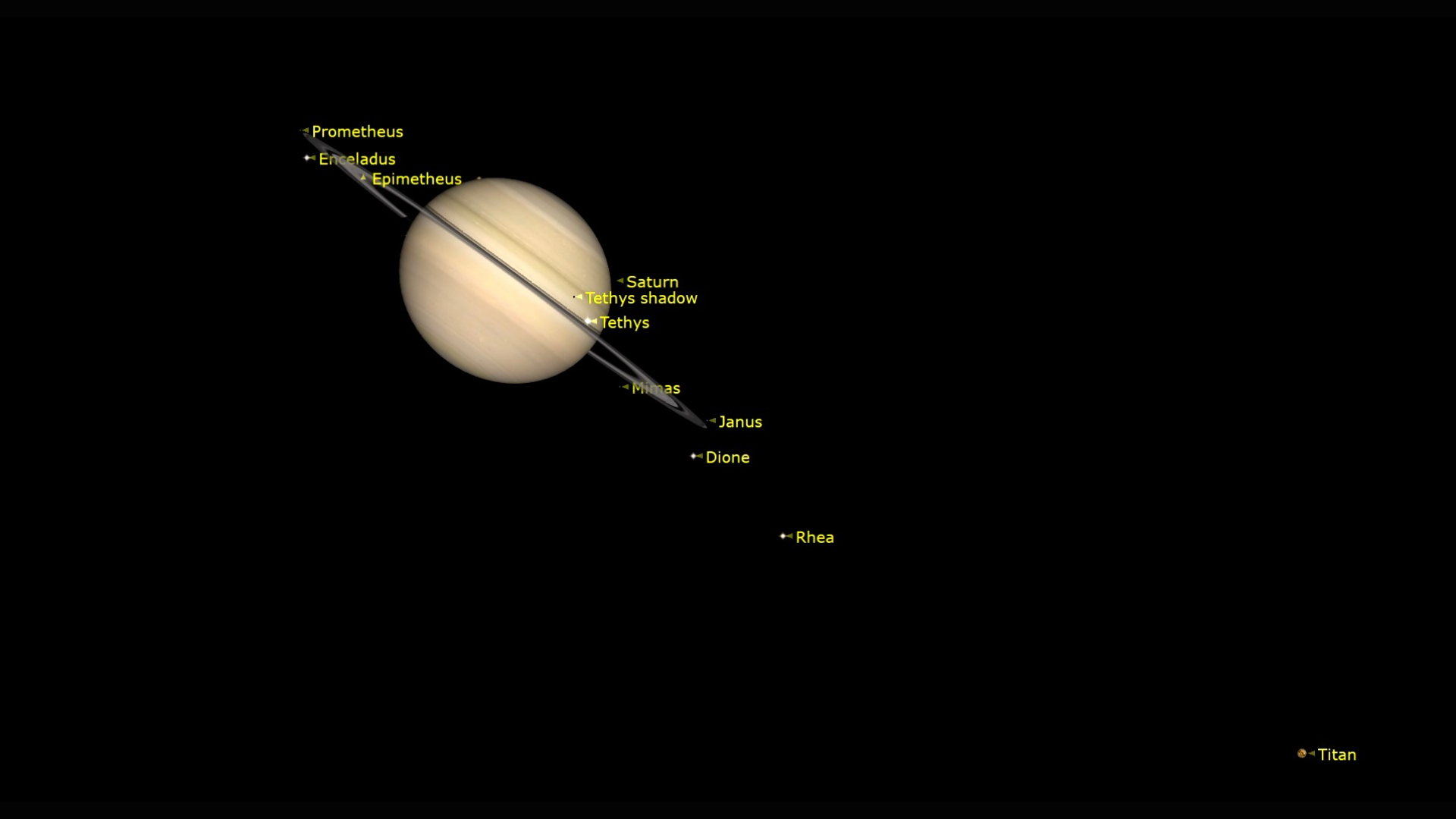

Saturn

During February, Saturn will continue to be accompanied by Neptune in western Pisces. Saturn's faster orbital motion will carry it past the more remote planet, minimizing their separation to 0.8 degrees on the days surrounding Feb. 20. Early in the month, Saturn's magnitude 1.15 creamy-yellow dot will pop out of the twilight in the southwestern sky at dusk, easily outshining the stars of Aquarius, Pisces, and Cetus that surround it. Viewed in a telescope at that time, Saturn will show an apparent disk diameter of about 16.1 arc-seconds and its extraordinary rings will subtend 37.5 arc-seconds. The rings, which were almost fully closed in late 2025, will continuously widen for the next several years, revealing their southern side. While Earth has remained near the ring plane, Saturn's moons have appeared closer to the planet's equator and produced occasional shadow transits. Saturn's descent sunward in the western sky after sunset will reduce its clarity in telescopes beyond about mid-month, though unaided eyes and binoculars will continue to show its creamy yellow dot against the brightening sky. Mercury and Venus will ascend to shine below Saturn after the first week of February. The waxing crescent moon will shine nearby on Feb. 19.

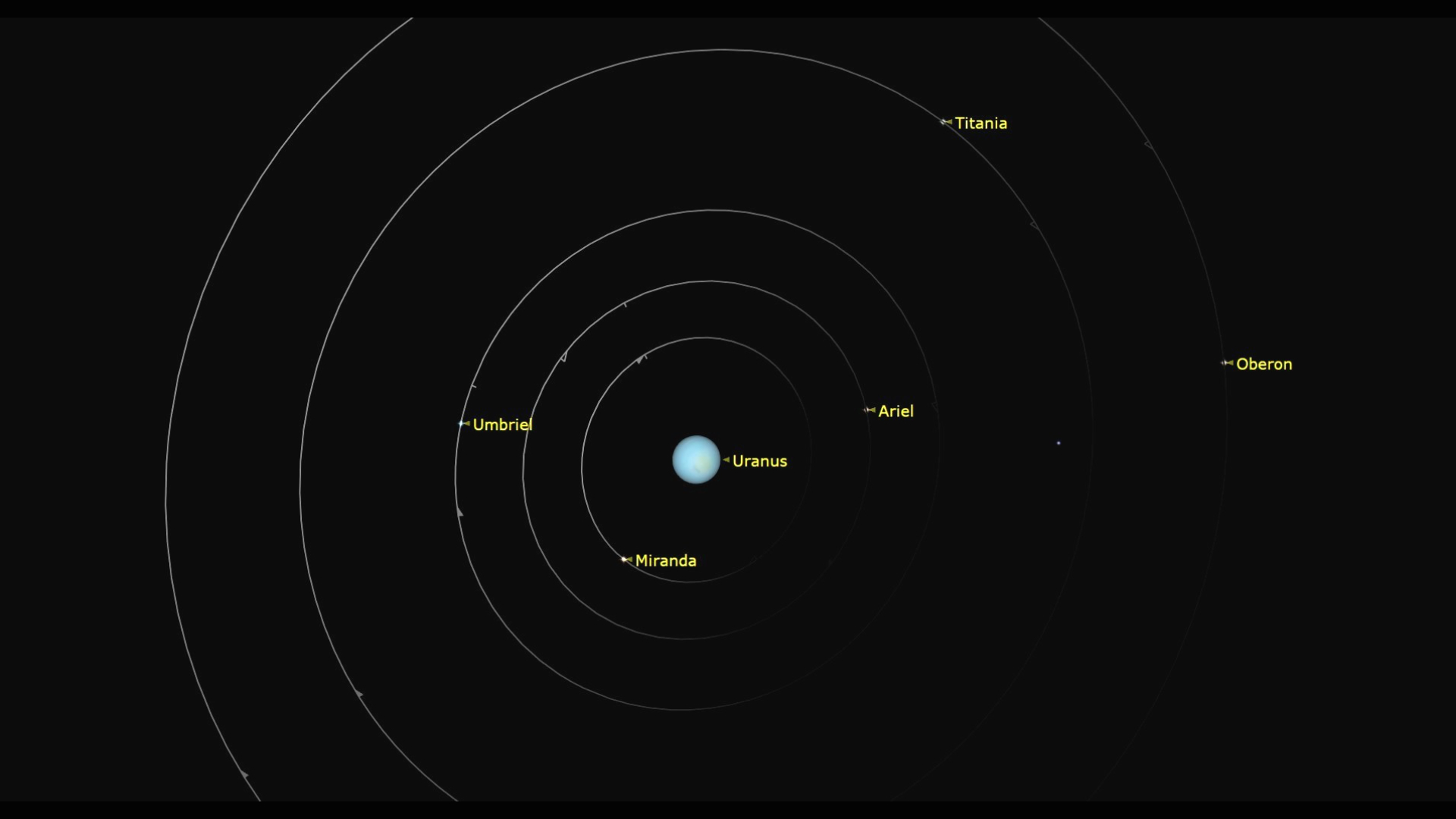

Uranus

Uranus will be well-placed for observing from the end of twilight to midnight during February while it shines in western Taurus close to the ecliptic and less than a palm's width to the lower right (or 5 degrees to the celestial south) of the bright Pleiades Cluster. The magnitude 5.7 blue-green planet is visible in a backyard telescope and through binoculars on moonless nights. Its westerly retrograde motion will slow to a stop on Feb. 4, and then it will resume its regular eastward motion.

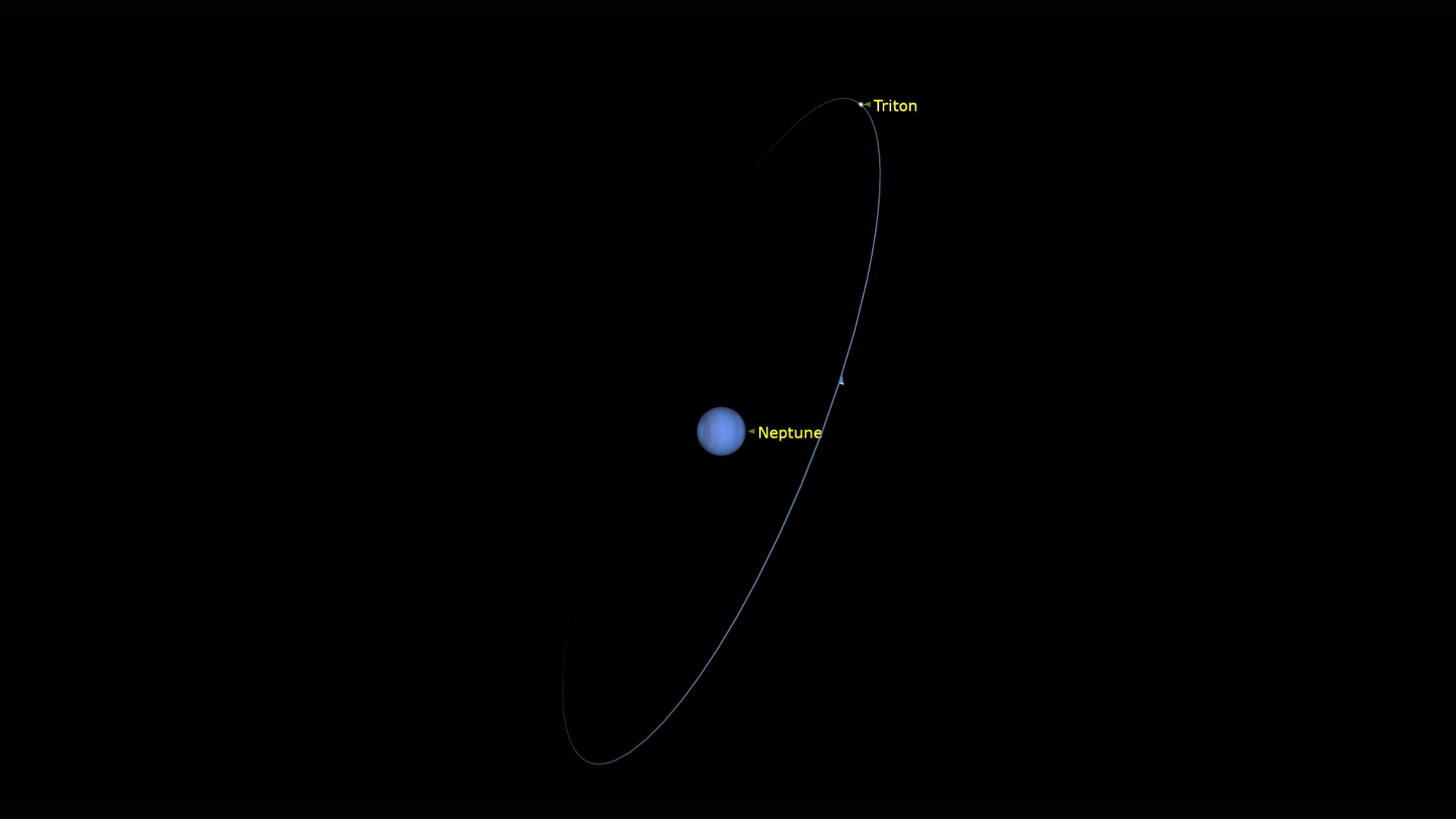

Neptune

During February, the distant, magnitude 7.9 planet Neptune will be located in the southwestern evening sky among the stars of western Pisces and a short distance from much brighter Saturn. Neptune's slower orbital motion will allow faster Saturn to pass 0.8 degrees to its left (or celestial south) on the evenings surrounding Feb. 20. Viewed through a backyard telescope in a dark sky, Neptune's 2.2 arc-seconds disk will resemble a dull blue star, though the opportunity for viewing Neptune will close around mid-month, when it will become too low in the sky and overwhelmed by the twilight sky

Skywatching terms

Gibbous: Used to describe a planet or moon that is more than 50% illuminated.

Asterism: A noteworthy or striking pattern of stars within a larger constellation.

Degrees (measuring the sky): The sky is 360 degrees all the way around, which means roughly 180 degrees from horizon to horizon. It's easy to measure distances between objects: Your fist on an outstretched arm covers about 10 degrees of sky, while a finger covers about one degree.

Visual Magnitude: This is the astronomer's scale for measuring the brightness of objects in the sky. The dimmest object visible in the night sky under perfectly dark conditions is about magnitude 6.5. Brighter stars are magnitude 2 or 1. The brightest objects get negative numbers. Venus can be as bright as magnitude -4.9. The full moon is -12.7 and the sun is -26.8.

Terminator: The boundary on the moon between sunlight and shadow.

Zenith: The point in the sky directly overhead.

Night sky observing tips

Adjust to the dark: If you wish to observe fainter objects, such as meteors, dim stars, nebulas, and galaxies, give your eyes at least 15 minutes to adjust to the darkness. Avoid looking at your phone's bright screen by keeping it tucked away. If you must use it, set the brightness to minimum — or cover it with clingy red film.

Light Pollution: Even from a big city, one can see the moon, a handful of bright stars, and the brightest planets — if they are above the horizon. But to fully enjoy the heavens — especially a meteor shower, the fainter constellations, or to see the amazing swath across the sky that is the disk of our home galaxy, the Milky Way — rural areas are best for night sky viewing. If you're stuck in a city or suburban area, use a tree or dark building to block ambient light (or moonlight) and help reveal fainter sky objects. If you're in the suburbs, simply turning off outdoor lights can help.

Prepare for skywatching: If you plan to be outside for more than a few minutes, and it's not a warm summer evening, dress more warmly than you think is necessary. An hour of winter observing can chill you to the bone. For meteor showers, a blanket or a lounge chair will prove to be much more comfortable than standing or sitting in a chair and craning your neck to see overhead.

Daytime skywatching: On the days surrounding the first quarter, the moon is visible in the afternoon daytime sky. At last quarter, the moon rises before sunrise and lingers in the morning sky. When Venus is at a significant angle away from the sun, it can often be spotted during the day as a brilliant point of light — but you'll need to consult an astronomy app to know when and where to look for it. When large sunspots develop on the sun, they can be seen without a telescope — as long as you use proper solar filters, such as eclipse glasses. Permanent eye damage can occur if you look at the sun for any length of time without protective eyewear.