When Nick Drnaso’s second book Sabrina was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2018, there was cause for celebration. It was the first graphic novel to ever be recognised in this way, thereby elevating an artform many still considered somewhat niche – and perhaps ultimately a little too lite for an award of such importance. Sabrina, an intensely brooding and existential work about a man whose missing girlfriend sends him into suicidal despair, was anything but lite.

Drnaso himself, however, was conflicted. The then 28-year-old from Chicago was still working part-time in a button factory; writing – and drawing – was very much a side-hustle. “It was great, actually,” he says of the day job. “I would stand at a processing machine and make about 2,500 buttons a shift. I loved it. You could listen to whatever music you wanted, and just zone out.”

As the fanfare around him gathered momentum, he continued to squirm. Even today, four years on, he’s in two minds about it. When we speak on Zoom one afternoon in July, the frown never quite leaves his face.

“I suppose the sole reason I was able to transition into the life I lead now – working solely on comics, I mean – was because of the nomination, yeah,” he concedes, almost reluctantly, while scratching at the beanie that sits tightly on his head. “I mean, I can appreciate praise, and prizes, at a distance, but I can’t internalise them. They don’t do anything for me, as far as validation goes.”

There were deeper feelings, too. Drnaso became convinced that what he did for a living was ultimately frivolous. “It was embarrassing. It felt like a shameful process, me making work that goes out into the world.” Why shameful? He shrugs. “Well, there’s a feeling that I shouldn’t be afforded this kind of privilege, that I shouldn’t be able to work on these things and be as indulgent as I am, and unchecked…” He trails off.

Sabrina, accomplished as it was (Zadie Smith called it a masterpiece), didn’t make the shortlist, and Anna Burns would go on to win it for her novel, Milkman. Nevertheless, Drnaso did stop making buttons, and turned to writing full-time. Otherwise, he points out, nothing changed. “My daily routine is exactly the same. I’m still sitting at the same desk, I still have the same tools. Yeah, maybe I can afford a slightly nicer scanner, a nicer computer, but that’s about it.”

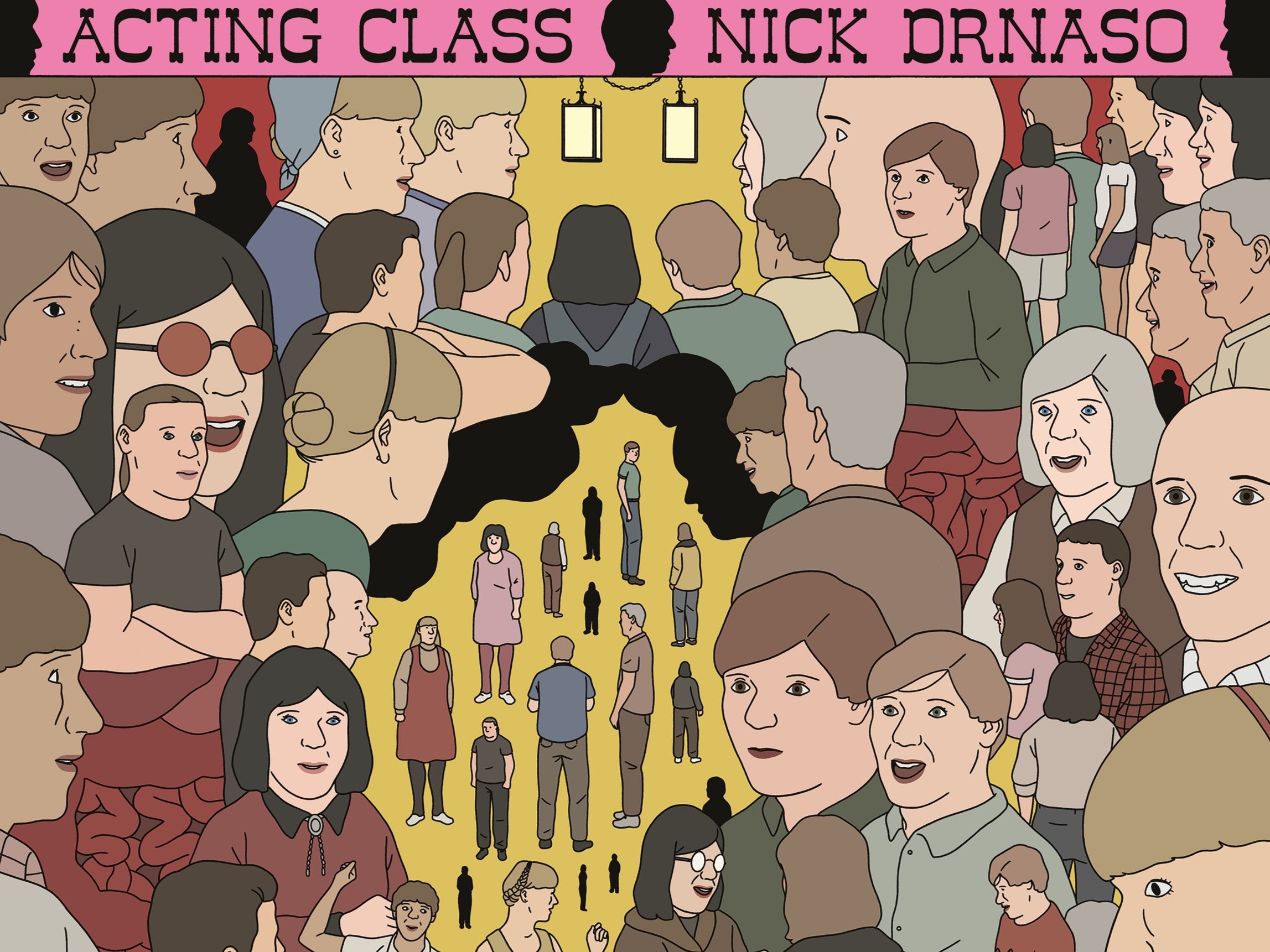

Clearly a tortured soul, Nick Drnaso is someone whose general sense of angst and alienation spreads throughout his work like spilt milk. His new book, Acting Class, is a wholly unsettling masterclass in disquiet. As with Sabrina, he utilises a minimalistic style in which women and men are rendered flat and very nearly featureless, with dashes for eyes and commas for mouths that only occasionally turn up into something resembling smiles. The story revolves around a group of disaffected Americans struggling as they attempt to make sense of the world around them, and their place within it. Each is lonely and disconnected, and some are harbouring unsavoury proclivities, but they come together in an acting class in the hope that the process might just help them flourish. Their enigmatic tutor holds each weekly class in increasingly remote places – a school at night, somebody’s house deep in the woods – and while the role-playing exercises he gives them are designed to challenge them, they also confuse them, blurring the lines between what is real, and what’s not.

It’s a confusion that affects the reader, too. What is Acting Class actually about? What’s the author trying to say? Drnaso admits that talking about this is, for him, difficult. “Once a book comes back from the printer, I put it on the shelf, and it’s dead to me. I immediately stop thinking about it, because there’s nothing to think about any more.”

This isn’t entirely true, of course, because he has to promote it. “It’s just, I can’t do anything about what the book actually is,” he says, frown deepening. A friend of his read it recently, and thought it was, “this, like, far-flung conspiracy theory. I had to tell him that it wasn’t, that it’s not that at all.”

And so what is it, his friend asked? “It’s something else,” he replied.

I can appreciate praise, and prizes, at a distance... but they don’t do anything for me, as far as validation goes.”— Booker Prize-nominated writer Nick Drnaso

Drnaso, now 33, lives in Chicago with his wife Sarah Leitten, a cartoonist and florist, and their two cats. They don’t let the cats outdoors, he explains, because of the myriad dangers there, and also because city cats disrupt the local biodiversity. “So they stay home, with us.” A shame for the cats, perhaps, but the gravid solemnity with which he says this illustrates perfectly the lengths he’ll go to protect his kin.

He grew up a quiet child, ineffably drawn to the dark side. He’d read about murders, and the 1986 nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, and would seek out disturbing videos online. These would shock and upset him, thus confirming that the world was something to be held at arm’s length. “I’ve always lived with… with feelings of uncertainty,” he says.

At 10 years old, he was sexually abused by a teenage neighbour. He didn’t talk about it to anyone until he was 27, just as he was preparing for Sabrina’s publication. Ever since the abuse, he’s been plagued with episodes of anxiety and depression.

“I think it simplifies things a little to create a narrative around it, to find a cause and effect,” he says, now cradling his bearded chin in the palm of his hand. “I’m not sure how you can ever [confirm] what it is that affects your worldview, but I guess that [the abuse] did create some hypervigilance in me, yeah, some anxiety and paranoia. You realise that people have the capacity for abuse and violence.”

He published his first book – Beverly, a series of interconnected short stories – in 2016, and began working on its follow-up within months of meeting his now wife. Whenever they weren’t together, he’d worry about where she was, whether she was safe. It was in this state that he wrote Sabrina. In the book, the internet and the TV news begin obsessing over conspiracy theories of what might have happened to Sabrina. Did she simply leave her boyfriend, or has she been killed? Is she being held hostage? And will she ever see her family again? Her boyfriend becomes increasingly stupefied, to the point where he barely functions.

It’s all rendered with extreme economy, the drawings unadorned, the text succinct. “I have to go home,” says one character. “I… um…” says another. Intermittently, actual emotion is expressed. “I am so angry at everybody,” Sabrina’s boyfriend confesses. To ameliorate him, a friend responds: “A lot of people are able to turn their grief into something positive.” He suggests that maybe he could seek “a job in law enforcement”.

Shortly before the book’s publication, Drnaso panicked and insisted that he wanted to pulp it. He didn’t like it any more, and didn’t want it out there in the world, convinced the narrative was too bleak for public consumption. He had a breakdown, which both his publisher and Leitten carefully steered him through. Months passed before, eventually, he went back to the book to rewrite parts of it. It was ultimately published to wild critical acclaim.

“I’m still ambivalent about it today,” he says, “and a little regretful. But I can’t do anything about it now.”

Acting Class may be slightly lighter in tone, but it’s still pitch black, and seems to further corroborate Drnaso’s worldview that there really is little good out there – and that if there is, it’s hard to find.

He tries again to sum up his intentions with the book. “I think that when I was writing it, I had a…” But now he falls into another prolonged silence, as if having to talk about it physically pains him, or at the very least exacts a toll. On screen, he does not make eye contact, and it’s difficult to watch him without feeling guilty for expecting him to converse. “No, sorry. I had a thought there, but I lost it. It’s gone.”

Recently, Drnaso sought a brief escape, some restorative downtime. He and his wife went with friends to the beach. They sunbathed for five hours. But, Drnaso says, “I just couldn’t understand how they could sit there for that long. I couldn’t relate to it. I felt anxious, and kind of useless.”

Perhaps he was missing his desk, and the structure that comes from being mentally active?

Slowly, he nods. “I think so, yes. Or at least we could have gone into town and visited a museum, a bookstore, something that had some kind of purpose, you know?”

‘Acting Class’ by Nick Drnaso is published by Granta