In summer 1985, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs rebuffed three offers to become a professor. “I told all of the universities that I thought I would be an awful professor,” he later revealed in an interview with Newsweek. Yet he still wanted to make a big impact in the education sector.

Jobs was 30 years old and ready for a new challenge. He’d resigned from Apple following a reorganisation, but not before telling the board what he wanted to do next. Having previously visited Brown University, he’d been told academics sorely wanted a powerful, personal workstation capable of helping them with their research. His aim, he told the Apple board, was to create a computer for the higher education market that best suited them.

When he made his announcement, jaws dropped, primarily because he said he was going to take five Apple employees with him. “These are very low-level people that you won’t miss, and they will be leaving anyway,” Jobs explained. But he wasn’t entirely telling the truth.

Jobs had little love for those running Apple at the time. “I think John [Scully, Apple’s then-CEO] felt that after the reorganisation, it was important for me to not be at Apple for him to accomplish what he wanted to accomplish,” Jobs told Newsweek. “He issued a public statement that there was no role for me there then or in the future, or in the foreseeable future. And that was about as black and white as you need to make things.”

To that end, he didn’t care that the five people he chose for his new venture were hugely important to Apple. Among them was Rich Page, one of the first four Apple fellows who had prototyped the company’s first portable, colour and 68020-based Macs. At the time, Page had been working on a machine referred to as the Big Mac, a powerful workstation for use in a university lab. It was a dual-boot machine allowing for the UNIX operating system as well as Mac OS but ended up being cancelled.

The five also included Bud Tribble, who headed Apple’s software development team and helped to design the classic Mac OS and its user interface; engineer George Crow, who designed the Macintosh 128K’s analogue board containing the power supply and video circuitry; and Susan Barnes, controller of the Macintosh division. Then there was Dan’l Lewin, a sales executive in the Mac team who created the Apple University Consortium and bulk sold Macs to two dozen institutions, including all Ivy League universities. All were disillusioned with life at Apple.

In that respect, Jobs was being honest. His chosen few likely would have left regardless of his intention to create afresh. Jobs didn’t waste much time, either. “Steve called me and I went for a long walk with him,” Lewin told PC Pro. “He told me he was going to start a company and it was going to focus on the things that I cared about – the things I’d pioneered at Apple from scratch.

“My thought process was that if I didn’t go and the company was successful, I’d kick myself, and if I didn’t go and it failed, I’d be curious as to whether or not my participation would have made a difference. At that time, I was running the entire education side of Apple, which was two-thirds of the company’s revenue – I’d built both a distribution strategy and a market framework for the higher education and research community. But I was a little frustrated by what was going on inside of Apple.”

Lewin was upset that Apple’s direct sales to universities had been affected by a reorganisation and the fact that product groups had stopped sharing information, which made his work more difficult. “One of the products which mattered to me was Big Mac,” he added. “I didn’t feel like I could trust getting the things done that needed to be done at Apple.”

Jobs’ new company offered a way forward and Lewin climbed aboard.

The next step

Apple was furious. Bill Campbell, then VP of marketing, was incensed that Jobs had hired Lewin because of the strong relationships he’d built with universities. Apple threatened to sue Jobs, who told the press he found the situation strange. “It’s hard to think that a $2 billion company with 4,300 employees couldn’t compete with six people in blue jeans,” he said.

Yet with Lewin and the others on board, it didn’t really matter that the new company – set to be called NeXT – was short on numbers. The team’s expertise would be enough to make an impact. “We have an immense amount of confidence in each others’ abilities and genuinely like each other,” Jobs told Newsweek. “And all have a desire to have a small company where we can influence its destiny and have a really fun place to work.”

It helped that the groundwork was already laid. Lewin’s network ran deep and he had a great understanding of the computing needs of higher education. “It had a reputation of being a niche market,” he explained, “but I turned that inside out and said, actually, it’s a superset of the real world.

“You have consumers who are replenished annually. You have researchers doing the most far out, extensive research on the planet. And you have these incredibly bright grad students who are pushing the edge of the envelope – they were doing fascinating, fantastic things with computers and foundation resources were funding their work. Major research institutions in the US are billion-dollar operations complete with this unique set of characteristics.”

As such, NeXT was confident that it could corner the market simply because the team knew what it would take. “We’d looked at what was going on in higher education and in primary research institutions and noted that they were using VAX machines, occasionally an Apollo workstation and, more and more over time, Sun Microsystems’ workstation.

“But any researcher worth their salt had a budget of a quarter to half-a-million dollars to gain access to a VAX, so we were looking at what they were doing with those machines. It led us to thinking about the architecture of the computer we wanted to build.”

Seeking perfection

It took a long time for the NeXT computer to be developed. Even in late 1986, as noted in Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs, the company only really had a $100,000 logo created by the American artist and graphic designer Paul Rand and some snazzy offices to show for their endeavours. “It had no revenue or products,” Isaacson wrote.

But that’s not to say it didn’t have anything of note. NeXT had secured a deal with Oxford University Press to bundle a digital edition of Shakespeare’s works with the machine, alongside the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, a dictionary and a thesaurus – thereby inventing the idea of searchable ebooks. NeXT had also nailed a deal with Lotus to develop a spreadsheet app for the NeXT’s operating system and enlisted other PC software companies to help.

NeXT had also hired Hartmut Esslinger. He was a master industrial designer who was being paid $2 million a year to create a design strategy for Apple. Jobs persuaded Esslinger to wind down his contract with Apple and set him to work on the creation of a cube case with perfect 90-degree angles and foot-long sides, even though it caused production problems later down the line.

Again, as Isaacson wrote, it’s difficult to get precise cubes out of tight moulds. The solution was moulds with separately created sides, but it added $650,000 to the manufacturing costs.

Jobs’ penchant for perfection also prompted the purchase of a new sanding machine. The screws inside the NeXT were plated as well, further inflating the costs. But at least the NeXT was moving forward.

“One of the design points was putting a digital signal processor in every machine, which no-one had ever done,” said Lewin, discussing the more important matter of what was going to go inside that cube. He was talking about the Motorola 56001 DSP, which allowed for fast processing of large matrix calculations, enabling the generation of CD-quality sound, speech, tone detection and music.

The NeXT computer would also include a Motorola 68030 processor running at 25MHz, built-in Ethernet, a high-resolution display and, crucially, a 256MB magneto-optical storage medium. “That was a lot of storage at the time,” Lewin told us. “It was also erasable, removable and non-magnetic.”

Powering up

One thing was clear: the team wanted to approach the higher education market in a different way. “We wanted to look at the personal computer sales and distribution model and the workstation application market opportunities,” Lewin said. “At the time, when you bought a PC the operating system came with it and you’d only pay for upgrades. You didn’t pay any monthly fees.

“But in the workstation business, Sun Microsystems being the dominant player, you’d pay a monthly fee to keep the operating system alive. So we wanted the power of a workstation machine with a PC business model, bundling Unix at the core. We wanted to dismantle the distribution side of the workstation market.”

Lewin knew that universities didn’t relish having to build power plants to run workstations. “That happened at Berkeley when they got 1,000 Sun 1 workstations,” he said. “Universities also had to pay system engineers to move computers down the hall because if they physically moved them, they’d violate their terms of agreement.”

The NeXT Computer would need 300W of power. “We could help create large labs,” Lewin said. On paper, it seemed like a perfect machine which, aligned with NeXTSTEP, should have been a winner.

Groundbreaking OS

NeXTSTEP was an object-oriented, multitasking Unix operating system based on the Mach kernel. “The distinguishing characteristic, at least in my mind, was the choice of Objective C and dynamic runtime binding,” Lewin said. “You could imagine professors building software and wanting to introduce an object into a simulation of some sort, looking at the reaction and checking what changed, and that’s what happened.”

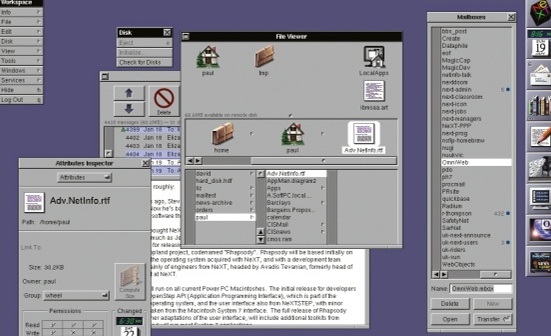

But the graphical mouse-based operating system was hugely innovative in other ways. It introduced the idea of the Dock seen in modern Macs. It had a 3D-style interface, high-resolution icons, real-time scrolling and window dragging, fluid graphics rendering and built-in networking support. “Networking is pretty fundamental to Unix and also where the world was heading,” Lewin explained.

A few years later, NeXTSTEP also ended up giving the world what could be described as the first digital App Store courtesy of the Electronic App Wrapper, a commercial electronic software distribution catalogue that allowed users to purchase, decrypt and install apps automatically. It’s just a shame it took so long for it to see the light of day.

Jobs had wanted the NeXT Computer to be released with the operating system within 18 months. That was never going to happen, but you couldn’t fault the ambition and attempt to push development along. While work continued, there was investment – notably from Ross Perot, the founder and CEO of Electronic Data Systems and Perot Systems. Yet there were also pushbacks, primarily from Microsoft founder Bill Gates, who went as far as to call the machine “crap”, stating “the optical disc has too low latency”.

But there was beef between Jobs and Gates. Jobs wanted Microsoft to create software for the NeXT Computer but Gates didn’t want to go in that direction. There was an attempt to license NeXTSTEP to IBM instead and create a de facto rival to Windows, but that potential deal collapsed.

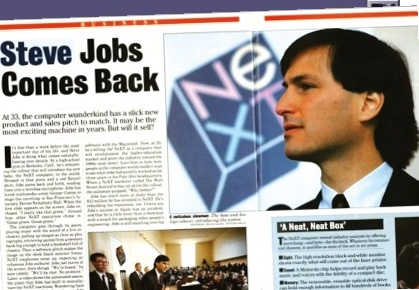

In the end, Jobs unveiled the machine before 3,000 people in San Francisco’s Davies Symphony Hall on 12 October 1988, some three years after leaving Apple. It came with the NeXTSTEP operating system as a machine exclusive, and Jobs, who had invested $12 million in the company, was in a confident mood as he showed off the machine’s ability.

It could quickly retrieve a line from Shakespeare, he demonstrated, and capably play a duet with a real violinist. Newsweek said the black cube “may be the most exciting computer in years”, and the presentation earned a standing ovation. Yet the computer was a pricey little thing. Jobs wanted the computer to cost no more than $3,000 when it was under development. It ended up selling for $6,500, and that was with a university discount.

If buyers wanted a printer, that would cost an extra $2,000. They’d also need to wait for version 1.0 of NeXTSTEP, which wasn’t released until 1989. But the fact that the company didn’t give up was admirable, and Jobs had a response to those who reckoned the computer was late. He told them it was actually five years ahead of its time.

The legacy

Even so, Lewin soon became concerned. Although the NeXTcube and NeXTstation were released in 1990, the company wasn’t in good financial health. “We had $120 million in the bank and I could see that being burned within 12 months, and that’s exactly what happened,” he said, resigning in 1991. “But in the end the asset was always software.” Other variations followed, until NeXT decided to concentrate on NeXTSTEP in 1993.

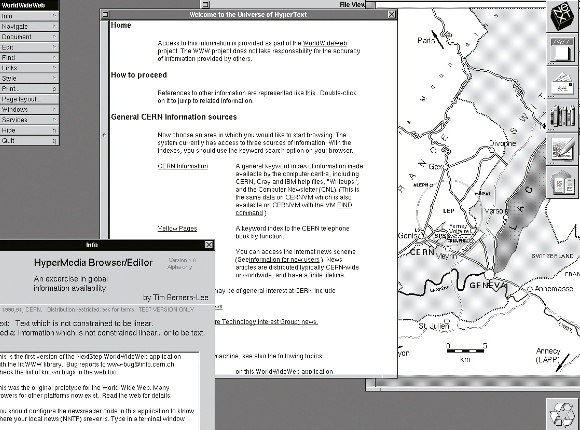

The company would go on to leave a strong legacy. British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee created the world’s first web server and web browser on a NeXT computer at CERN, hosting the first web page in December 1990. The video games Doom and Quake were also created on the platform – developer John Carmack said id Software bought its first NeXT out of personal interest and ended up spending $100,000 on the machines.

“It is funny to look back; I can remember honestly wondering what the advantages of a real multi-process development environment would be over the DOS and older Apple environments that we were using,” Carmack wrote on Quora in 2016. “Actually, using the NeXT was an eye-opener, and it was quickly clear to me that it had a lot of tangible advantages for us, so we moved everything but pixel art (which was still done in Deluxe Paint on DOS) over.”

NeXT’s biggest legacy, however, involved Apple. In December 1996, Apple acquired NeXT for $427 million in cash, shares, stock options and debt. Apple wanted NeXTSTEP to become the foundation for a new Mac operating system to replace classic Mac OS. The move also heralded Jobs’ return to the company.

It meant Jobs went full circle, proving he was still able to influence Apple’s direction even when not working at the company. “If you look at the Mac today, you can trace the operating system right back to NeXTSTEP,” Lewin said. There’s the Dock, many base APIs, the Objective C runtime, the manner in which third-party apps work, and so much more.

So while NeXT didn’t prove to be hugely successful as an entity in and of itself, it had an immense impact on computing as a whole. And far from having an adverse impact on Apple, it played a large role in being its saviour. In that sense it was a successful failure, one that ultimately ended up making Jobs a household name.

“It was,” Lewin said, with a level of understatement, “an interesting moment in time.”

This review first appeared in Issue 361 of PC Pro.