A new X-ray analysis of a 3,000-year-old painting of Egyptian pharaoh Ramses-II has revealed what archaeologists suspect are strange “touch-ups” made to the artwork over years.

Ancient Egypt has no known word for “art”, say researchers from CNRS in France, adding that the civilisation may have been “extremely formal” in its creative expression, including in the works of painters in funerary chapels.

However, the scientific analysis of ancient Egyptian paintings in the past have mostly taken place in museums, while the painted surfaces, preserved in funerary chapels and temples, have remained “somewhat estranged“ from rigorous studies, archaeologists say.

Now, using a new type of portable X-ray scanner, scientists could study paintings at the site of Ramses II in the tomb of Nakhtamon – a priest responsible for the daily provisioning of altars during the pharaoh’s reign.

In the remains of Luxor, Egypt, researchers also found new details in the paintings of Menna, who is thought to have been responsible for the ancient city’s agricultural production.

Signs of touch-ups made to these paintings over time reveal what seem to be artistic license exercised by ancient painters, according to the study, published in the journal PLoS One on Wednesday.

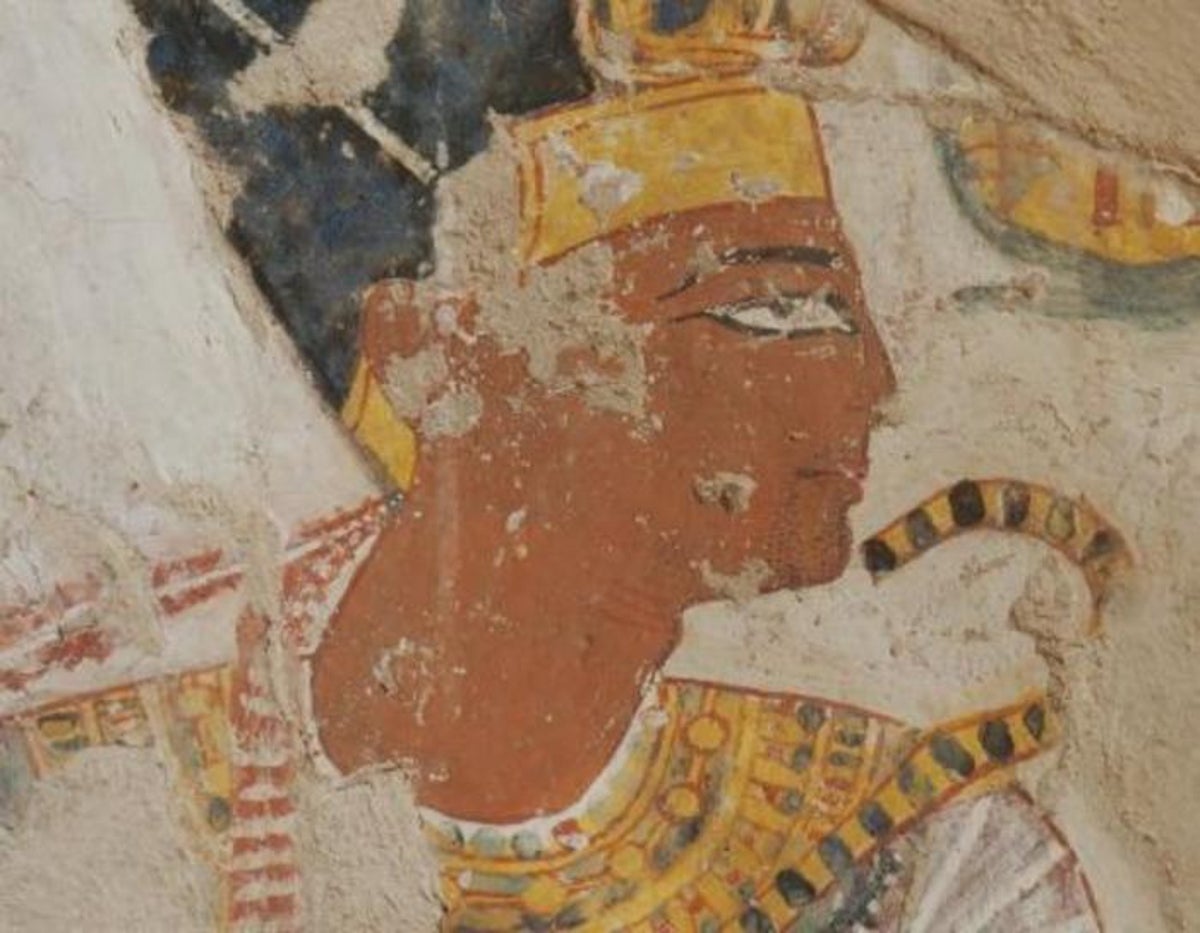

Citing an example, researchers say the headdress, necklace, and sceptre in the image of Ramses II appear to be “substantially reworked,” though remaining invisible to the naked eye.

They could also find other subtle oddities in the painting that has previously been discussed in detail as it shows a rare but precise representation of a pharaoh presenting a budding beard.

While the stubble on Ramses II’s chin in this portrait has been seen as a visual symbol of grief, hypothetically linked to the death of his father and his rise to the throne, closer examination finds that the enthroned figure in front of him in the painting is the god Ptah, not his deceased father Seti I.

New analysis of the painting also revealed Ramesses’s protrusive Adam’s apple – a detail, according to archaeologists, that was “interestingly never shown in ancient Egyptian art”.

In Menna’s tomb, they say the position and colour of an arm were modified.

The new X-ray analysis has found pigments which were used to represent skin colour that differ from those first applied to these paintings.

However, scientists say the the purpose of these “subtle changes” still remain uncertain.

They suspect that ancient painters, at the request of the individuals who commissioned their works, may have made some of these changes.

Alternatively, they theorise that artists, at their own initiative, may have added “personal touches” to conventional motifs as their vision of the works changed.

The findings, however, conclusively shed light on the fresh insights archaeologists could obtain from using such portable tools for nondestructive in situ chemical analysis and imaging.

Chemical analysis performed by the scientists in situ along with their 3D digital reconstructions of the works could make it possible to restore the original hues, the study noted.

The new study also suggests ancient Egyptian pharaonic art and the conditions of its production may have been more dynamic and complex than once thought.

In future studies, the team hopes to analyse more paintings in situ to search for new signs of the craftsmanship and intellectual identities of ancient Egyptian draughtsmen-scribes.