Webb’s mid-infrared instrument reveals a stunning spiral galaxy in a whole new light, showing what’s going on behind an already-gorgeous Hubble Space Telescope photo.

In the wavelengths of light our eyes can see, IC 5332 is the perfect image of a spiral galaxy. 29 million light years away, it’s a bit larger than the Milky Way (about 66,000 light years wide) and almost exactly face-on toward Earth, offering us a perfect view.

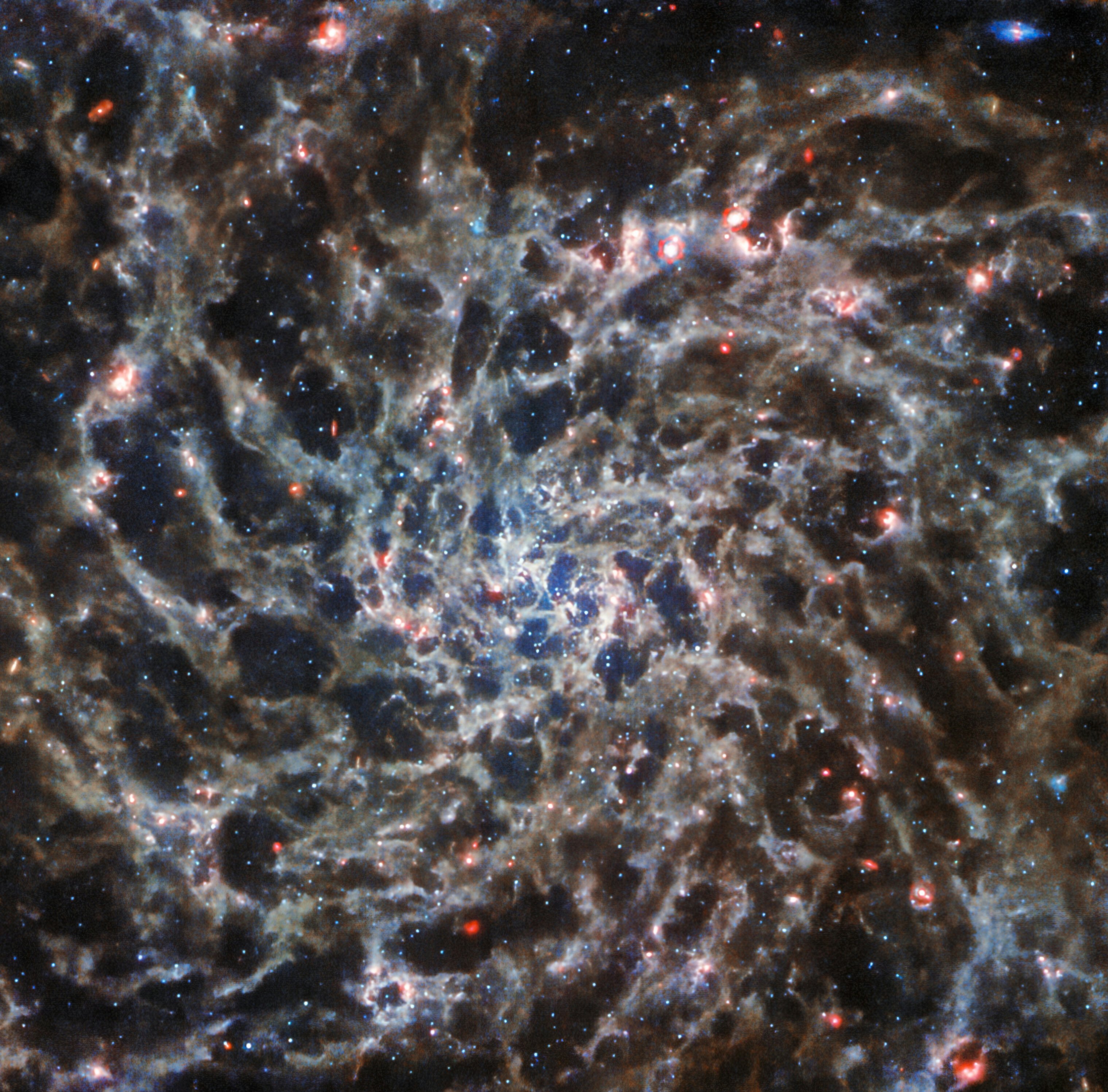

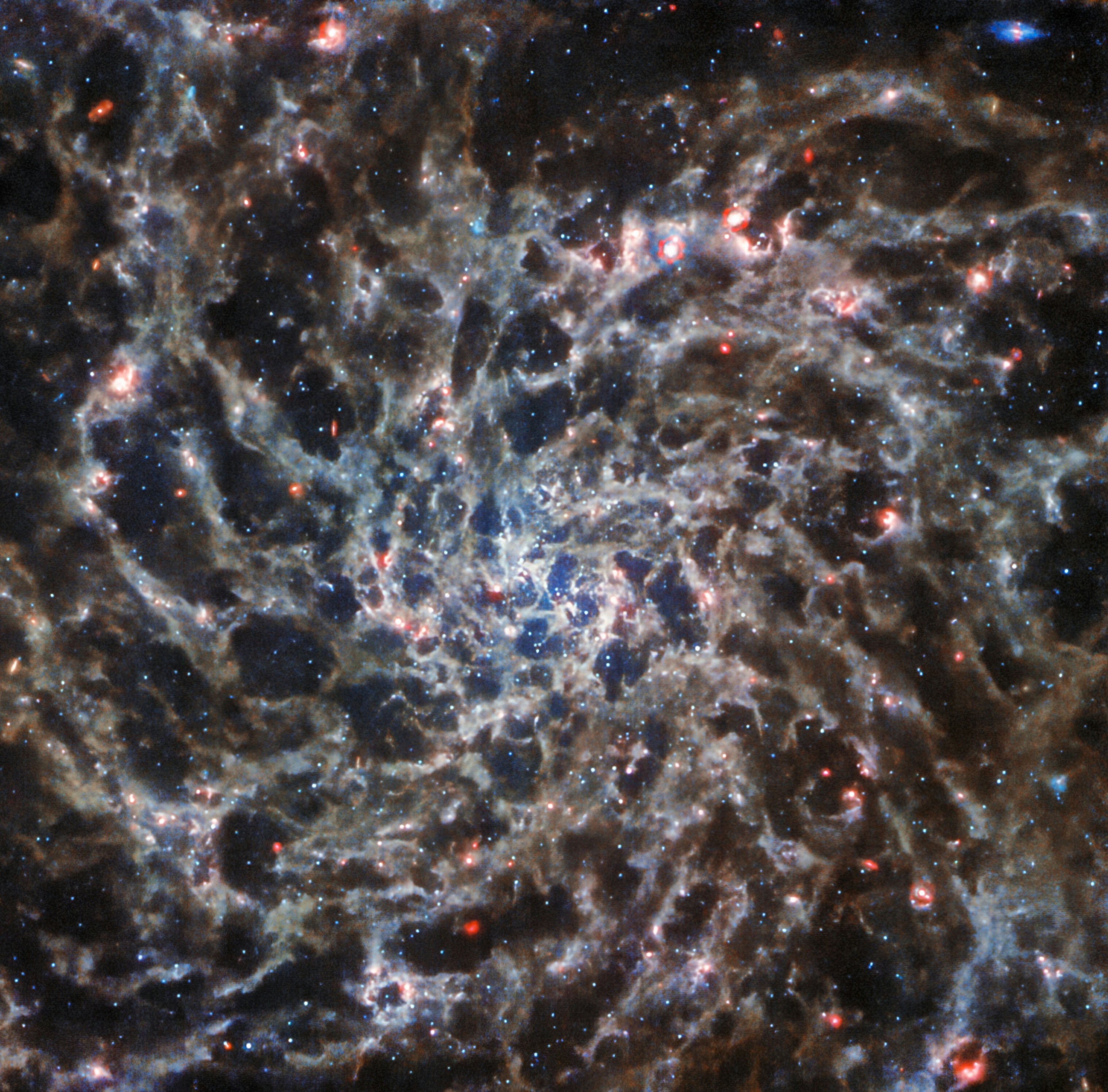

Hubble captured a dazzling image of the galaxy’s glowing arms of stars, swirling outward from a blazing center, with dark bands in between. It’s classic. But viewed in infrared light, through the James Webb Space Telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument, the galaxy looks completely different — as if we’ve wandered into the Upside Down from Stranger Things.

The overall spiral shape is still there, but the familiar swirling bands of bright stars and dark dust become a strange, intricate web of glowing matter, with distant galaxies showing through the gaps. Even the stars themselves look different; some of the stars that shine brightest in the familiar Hubble image are missing in the infrared version, replaced by different ones.

It’s a gorgeous — and slightly disconcerting — example of how the physics of light can reveal some things and hide others.

Those dark bands of dust between the bright, starry spiral arms look dark to us because the dust scatters and blocks shorter wavelengths of light, including visible and ultraviolet. But longer wavelengths of infrared light can shine right through the dust, making those dark bands transparent — and revealing a whole new structure behind the familiar swirling bands.

That’s also why Webb and Hubble see a different set of stars in IC 5332. Some stars shine brighter in particular wavelengths. Young, massive stars tend to blaze with high-energy ultraviolet light, for instance, while smaller or older stars are usually brighter in infrared. By viewing the same galaxy through both telescopes, astronomers can see them all instead of just one set or the other.

Both Hubble and Webb can see the shortest infrared wavelengths — what’s called “near-infrared” because its wavelengths are “next door” to visible light on the electromagnetic spectrum. But to give us this Stranger Things-esque view of IC 5332, Webb needed to capture slightly longer wavelengths of light, in what’s called the “mid-infrared” part of the spectrum. That’s something Hubble can’t do, because the older space telescope just isn’t cool enough — literally. If Hubble tried to view the universe in mid-infrared light, it would mostly see the heat from its own mirrors, rather than the glow of distant cosmic objects.

Webb can take mid-infrared images of galaxies like IC 5332 because its Mid-Infrared Instrument, MIRI, has its own cooling system that keeps the instrument at -266°C (-447°F). That’s just 7°C (45°F) above absolute zero, at which there’s no heat – no energy – at all. All of Webb’s other instruments run at a comparatively balmy -233°C (-387°F).

In other words, Webb — like Stranger Things’ Mind Flayer — likes it cold.