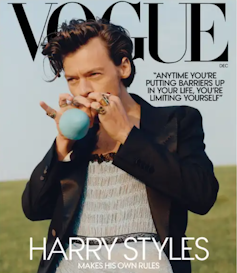

The image of pop star Harry Styles wearing a Gucci dress on the cover of Vogue in December 2020 garnered much publicity and controversy. It resonated particularly with a gen-Z readership increasingly embracing gender fluidity.

In the accompanying interview, Styles described women’s clothes as “amazing”, insisting that men should not be limited by binary ideas of style. “Any time you’re putting barriers up in your own life, you’re just limiting yourself,” he said.

Styles is directly confronting socially dominant ideas of what it is to be a man. A new exhibition at London’s V&A museum called Fashioning Masculinities places Styles’ Gucci dress right at its centre. It teaches us that sartorial transgressions like these have a rich and complex history and suggests that men’s fashion has always been at the heart of the politics of gender.

Roles and stereotypes

There is a stereotype that men – at least heterosexual men – are uninterested in fashion. Such stereotypes are inseparable from the broader logic of patriarchal society. Men are judged according to their economic power, and women are objectified into what the feminist Rosalind Coward called “the aesthetic sex”.

As part of this, fashion is a way through which women negotiate patriarchal sexual relations and popular ideas of femininity. In turn, the beauty industry reproduces impossible ideals, pressuring women to perfect an ever-increasing amount of their bodies.

The rise of the female or queer gaze has not resulted in the same social scrutiny of men’s bodies. Accordingly, fashion has become labelled as an essentially feminine pursuit. The fashion theorist Jennifer Craik went as far to say that the history of men’s fashion can be understood as a “set of denials”.

These not only dismiss fashion as frivolous or unmanly, but also perpetuate a harmful form of masculine self-denial. This finds its high point in the caricature of the emotionless Victorian male, attired in sombre black, performatively displaying moral authority and self-restraint. It is a short leap from these 19th-century denials of feelings and flamboyance to modern ideas of toxic masculinity.

However, this seems to contradict the pattern of the natural world, where the male of the species is generally the more spectacularly patterned. Peacocks, for example, have bright plumage to attract the less flamboyant peahens. Historically, this was also the case for men’s fashion, which became more spectacular in direct proportion to one’s social status.

In Fashioning Masculinities, we learn that pink cloth required expensive imported dyes. Now considered effete, pink was worn by 16th-century males to signify financial strength and even physical bravery. Contemporary designers like Harris Reed (below) now deliberately reference this aesthetic as an expression of gender politics.

In 1930, the Freudian psychoanalyst John Carl Flügel argued that a reversal of this pattern could be identified at the end of the 18th century. In what he called the “great male renunciation”, men’s fashion became austere and decoration the sole preserve of womenswear. This change is related to the rise of desk-based professions and their associated uniforms following the industrial revolution.

This pattern arguably remained constant until the 1960s, when a resurgent consumer culture, celebrity pop stars, and the general relaxation of social mores kickstarted a new “peacock revolution” in menswear. Now men felt comfortable wearing their hair long like women and dressing in newly psychedelic resplendence.

In 1971, David Bowie would appear on the cover of The Man Who Sold the World wearing a man-dress by London designer Mr Fish. This was deemed too shocking for an American audience, and the cover was replaced with an illustration of the alpha-male cowboy John Wayne.

Culture wars

Harry Styles is demonstrably not the pioneer of man-dresses. However, his gender-fluidity does reissue an important symbolic challenge to what sociologists call “normative man”. This is especially significant, given that this shoot would see Styles become Vogue’s first male solo cover star.

The decision to grant Styles this platform, for this particular purpose, was criticised by the black American actor Billy Porter. Porter has become famous for playing the MC of the New York 1980s drag balls in the Netflix hit Pose. He is also famous for wearing glamorous evening gowns on the red carpet.

For Porter, Vogue’s choice of Styles was both cultural appropriation and white privilege. In the LA Times in 2021, Porter complained:

This is politics for me … This is my life. I had to fight … to get to the place where I could wear a dress to the Oscars and not be gunned down. All he has to do is be white and straight.

For some, wearing women’s clothes as a heterosexual male will always trivialise the intersectional struggles of LGBTQ+ communities. Perhaps this becomes less of a problem if we can detach menswear from the question of sexuality. But it is easier said than done.

Flügel insisted that the two are indivisible. For him, even neck-ties were phallic symbols. Though restrained, the sombre Victorian suit was nevertheless an expression of professional status that would have attracted potential suitors. For austerity-era males denied the financial status of previous generations, the alpha-male “gym-bro” culture uses the body rather than fashion as a medium of masculine sexual display.

Styles’ gesture represents a significant redefinition of masculinity that must be considered transgressive. Yet, as Porter recognises, it also has the unfortunate consequence of disguising the political persecution of sexual and racial minorities behind aesthetic questions of play and performance.

Ultimately, subverting the codes of masculinity is still easier when you already embody the characteristics that straight, white, patriarchal culture demands of its male icons.

Richard Hudson-Miles does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.