Despite the alarming regularity with which artificial satellites intrude on photos snapped by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, the science done with data from the telescope has not suffered, a new study reports.

"To date, not one Hubble science program has been affected by satellite trails," representatives of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Maryland, which carries out science operations for Hubble and conducted the latest study, wrote in a statement published Monday (June 5).

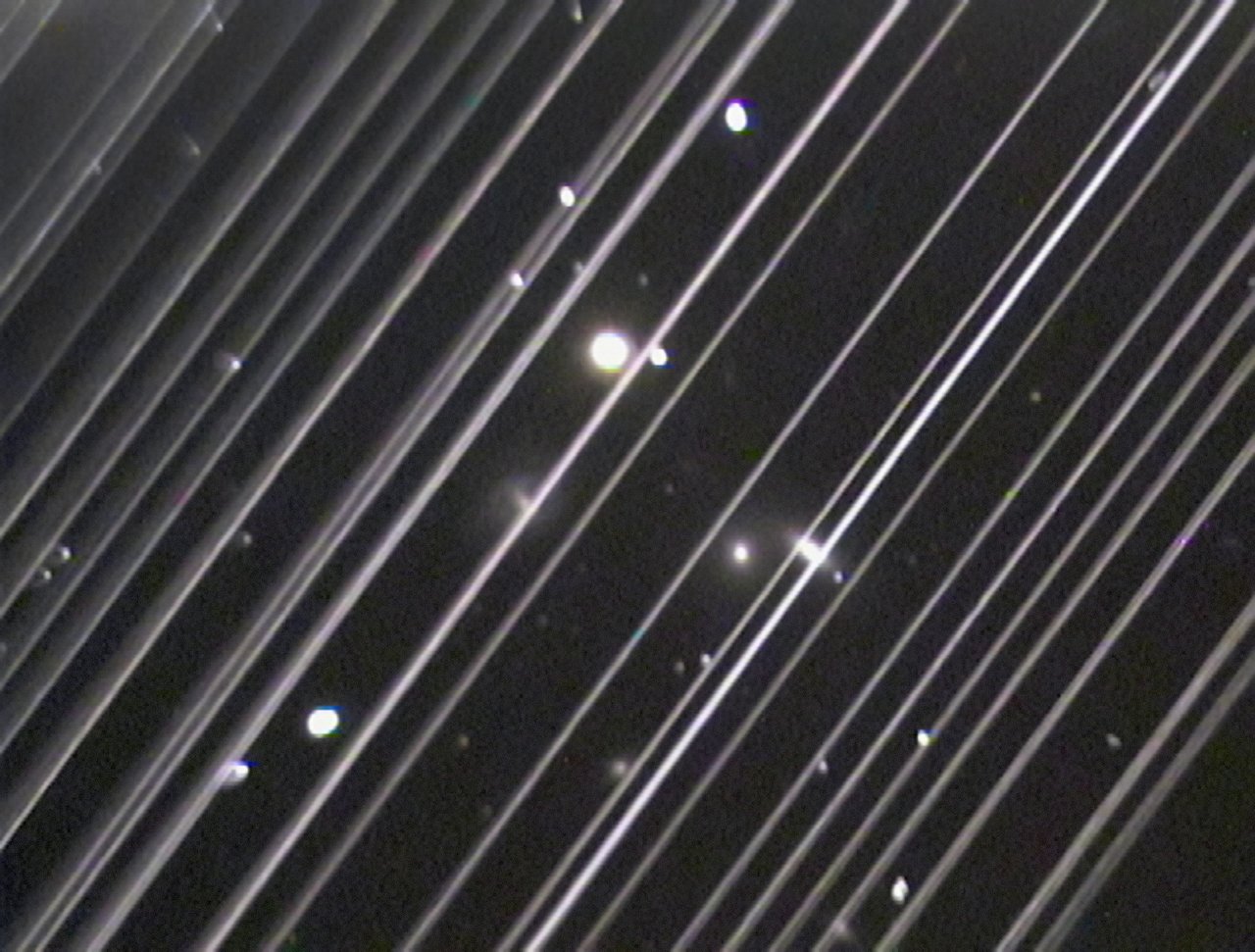

Skywatchers, professional astronomers and the International Astronomical Union have long sounded alarm bells about the rising number of artificial satellites significantly brightening the night sky and photobombing telescope images. Those unwelcome guests glide in orbits higher than Hubble's decaying one, which is now at a sensitive spot some 334 miles (538 kilometers) above Earth, and appear in the telescope images as bright streaks, thanks to sunlight reflecting off their bodies. They outshine faint stars and galaxies in deep space and ultimately endanger precious data about the cosmos, astronomers have argued.

Related: The best Hubble Space Telescope images of all time!

Findings from the latest study disagree on the acuteness of those concerns, however, at least for images captured by Hubble. The study does not mention the impact on research due to satellite trails cropping up in observations by ground-based telescopes.

"The good news is, in the vast majority of cases, satellite trails do not appear to threaten our ability to do science with the Hubble Space Telescope," David Stark, a staff scientist at STScI and an author of the new study, said on Monday at the 242nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society being held in Albuquerque and online. "Cosmic rays are a much bigger issue when you look at individual exposures."

A typical satellite trail is "relatively thin," taking up some five to 10 pixels in a Hubble image — about 0.5% of the photo's total pixel count, according to Stark. In comparison, ubiquitous cosmic rays, particles traveling at extremely high speeds that show up as satellite-like streaks in telescope images, affect three to six times more pixels and can render entire exposures useless.

The standard practice for Hubble observations is to snap multiple exposures of the same slice of the night sky where a celestial target resides. If a few images are contaminated, other similar exposures are usually combined to effectively erase the impacts of satellite trails or cosmic rays and recover a snapshot of the pristine night sky, Stark said during his presentation.

There are about 9,700 active and dormant satellites in orbit right now, with over 4,000 launched by SpaceX as part of its Starlink megaconstellation and a smaller contribution by OneWeb, which had flown a total of 582 satellites into orbit by early March. By the time 2030 rolls in, more than 100,000 satellites are expected to crowd low Earth orbit, according to a report by Astronomy Magazine's Nathaniel Scharping.

Despite the predicted spike, scientists behind the new research say it is possible to identify and erase satellites' pencil-like presence from telescope images without impacting the quality of research. One way to do so would be using a newly developed algorithm, whose image analysis technique sums up the light from every straight path across an image to flag contaminated pixels betraying satellite trails, scientists say.

"When we flag them, we should be able to recover the full field of view without a problem, after combining the data from all exposures," Stark said in the same statement.

To test out its efficiency, he and his colleagues applied the algorithm to the past 20 years of Hubble data, specifically images captured by the telescope's workhorse instrument called the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). The team then plotted the number of satellite trails per hour and the fraction of individual exposures by Hubble polluted by satellite trails.

While the brightness of the trails remained about the same across those two decades, the rate at which streaks showed up in images doubled: from once ever three to four hours in 2002 to every one to two hours in 2022, the team found.

The software — which is five to 10 times more sensitive than its predecessor, also built by STScI — is efficient at "digging into the weeds" of Hubble images and erasing effects of even weak trails that are hard to see with the naked eye, Stark told reporters on Monday.

The algorithm did miss satellite streaks and at times even found false trails in image corners, where the straight lines it was trained to trace are shorter than the rest of the image, making the tool less sensitive, according to the study.

Despite the drawbacks, even if satellite contamination in telescope images mushrooms as expected from the current rate of one bright streak in every 10 pictures to one in every image, "we are still pretty confident that we can remove their effect," he said.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @skuthunur. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.