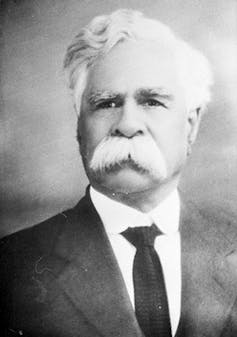

In December 1938, Yorta Yorta man William Cooper took part in a protest organised by the Australian Aborigines’ League to deliver a letter to the German consulate in Melbourne condemning the “cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi government”.

The protest came weeks after Kristallnacht, an outpouring of violence against Jews by the Nazi regime in Germany, which resulted in the burning of synagogues, damage to Jewish businesses, imprisonment of tens of thousands of Jews and many killings.

Holocaust educators in Australia have taken up Cooper’s march as an example of being an “upstander”, rather than a “bystander” during the Holocaust.

It’s also an example for the thousands of school students who visit Holocaust museums in Australia each year of the type of personal and political action needed to ensure the Holocaust does not happen again.

But what do Australians know about Cooper and his protest? The answer from a recent survey appears to be not very much.

Holocaust awareness high, but not Australia’s role

The national survey of more than 3,500 Australians, funded by the Gandel Foundation, has found people’s general knowledge of the Holocaust is high – 80% of respondents knew the Holocaust happened between 1933 and 1945 and 67% knew the Holocaust refers to the genocide of Jews.

But there were significant gaps when it came to Australia’s connections to it.

Only 16% of respondents, for example, knew who Cooper was. Just 11% knew Australia refused to accept more Jewish refugees during the Evian Conference in 1938, a meeting of 32 countries to discuss the German-Jewish refugee crisis. And only 7% of respondents knew Australia has one of the largest number of Holocaust survivors in the world per capita, outside Israel.

Read more: How COVID has shone a light on the ugly face of Australian antisemitism

While these figures are sobering and a cause for reflection, other findings are more positive.

The survey not only measured Australians’ knowledge of the Holocaust, but also their Holocaust awareness. This is defined as acknowledging the true scale of the Holocaust and caring about Holocaust education.

Almost nine in ten Australians (88%) agreed we can all learn lessons for today from what happened in the Holocaust. And despite millennials having generally less overall knowledge of the Holocaust than older generations, they have higher levels of Holocaust awareness.

Our survey is the first of its type undertaken in Australia, and similar to other surveys overseas.

How Holocaust awareness is linked to Australian history

According to a recent biography of Cooper, what’s often missing from commentary about his 1938 protest against the Holocaust was the fact he wanted to use the opportunity to draw attention to racism and violence against First Nations peoples in Australia, too.

The author, Bain Atwood, argued the emphasis on this one event overshadowed the broader activism of Copper and the Australian Aborigines’ League on issues like First Nations representation in government, land rights and acknowledgement of colonial dispossession and violence.

The concern here is that a continuing focus on the Holocaust could detract from understanding our own difficult history in Australia.

Our survey found, however, a strong relationship between Holocaust awareness and positive feelings towards religious minorities, refugees and asylum seekers and First Nations Australians. The findings suggest, though, more work needs to be done to make the connections between Australian history and the Holocaust explicit. This includes our history of colonial genocide and our treatment of asylum seekers and refugees.

This does not mean making simplistic comparisons, but acknowledging different histories and memories and how they interconnect. Our survey found, for instance, just over half the respondents agreed with the statement: “the Stolen Generations are an Australian example of genocide”.

Support for greater Holocaust education is high

Promisingly, our survey found higher levels of Holocaust awareness among those who had visited a Holocaust museum or taken part in specific Holocaust education. There was also strong support among our respondents (66%) for compulsory Holocaust education in schools.

There will soon be new or significantly redeveloped Holocaust museums in every state and territory in Australia. Australia also recently became a full member of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, which includes a commitment to include the Holocaust in school curriculums and institute a national day of commemoration (which Australia did last year).

The federal government has also supported pilot projects for a Holocaust Memorial Week in 2018 and 2022.

The Victorian government, meanwhile, has supported the development of specific resources to help educators teach the Holocaust in schools. And a growing number of Australian educators have graduated from Gandel Foundation’s intensive teaching programs at Yad Vashem, the world’s largest Holocaust memorial museum in Israel.

With the rise of anti-Semitism – including online hate and Holocaust denial and distortion – understanding the relationship between Holocaust awareness and efforts to combat racism today is more important than ever.

Steven Cooke received funding from the Gandel Foundation to undertake this research. He is a member fo the Australian delegation to the Internatioanl Holocaust Remembrance Alliance.

Andrew Singleton receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Gandel Philanthropy

Dr Donna-Lee Frieze donna-lee.frieze@deakin.edu.au receives funding from the Gandel Foundation as a lead researcher for the Gandel Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Survey 2021, is a lead researcher on the project Holocaust Memorial Week 2022 with a grant from the Department of Education, Skills and Employment and a delegate for the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. She is affiliated with Deakin University.

Matteo Vergani receives research funding from the Victorian government, Gandel Philanthropy, the Australian federal government, and the Canadian government.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.