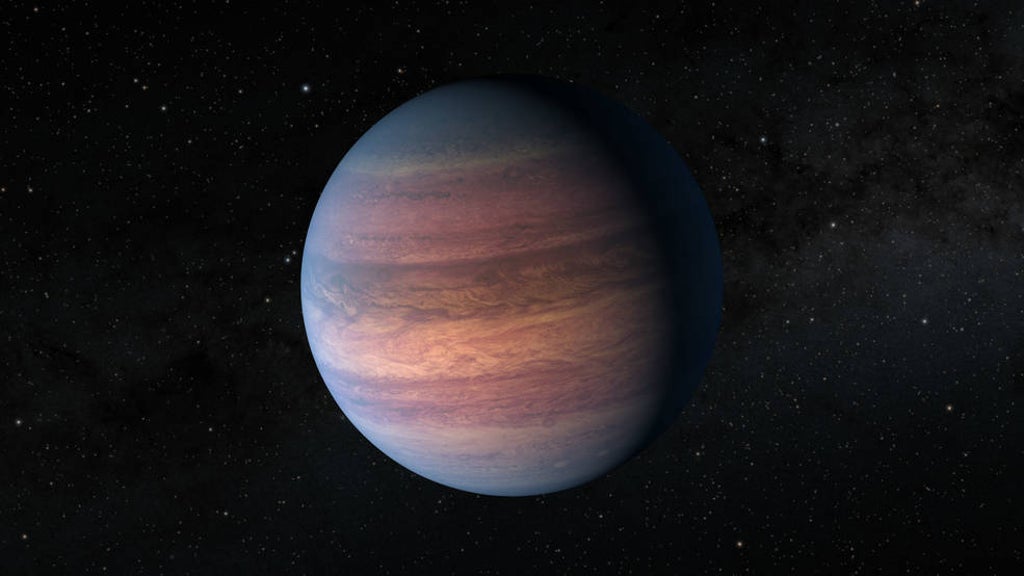

A group of citizen scientists and astronomers have found a new planet the size of Jupiter.

The enormous world, called TOI-2180 b, is located 379 light-years away and takes 261 days to orbit its star – longer than many other gas giants outside our solar system – and a temperature of around 76C. This is warmer than Earth, but abnormally cold for similar exoplanets.

TOI-2180 b is also thought to be denser than Jupiter, with as many as 105 Earth masses packed inside. This suggests that it is not made of elements like hydrogen and helium.

There could be rings and moons orbiting it, too, something that has not yet been found with certainty outside of our own solar system.

The citizens, who use Nasa telescope data to discover other worlds, collaborated with professional astronomers in a “global uniting effort”. While professional astronomers use algorithms to scan the data, citizen scientists inspect it by eye using a program called LcTools.

This resulted in former US naval officer Tom Jacobs noticing a plot showing starlight from the star TOI-2180 dimming by under half a per cent over a 24-hour period. Although his may not sound like much, the data suggests that an orbiting planet could be responsible for the dimming.

By measuring the amount of light that dims as the planet passes, scientists can estimate how big the planet is and, in combination with other measurements, its density. But a transit can only be seen if a star and its planet line up with telescopes looking for them.

“With this new discovery, we are … pushing the limits of the kinds of planets we can extract from TESS [Nasa’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite] observations,” Diana Dragomir, assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, said. “TESS was not specifically designed to find such long-orbit exoplanets, but our team, with the help of citizen scientists, are digging out these rare gems nonetheless.”

The manual effort of citizen scientists is, in some instances, superior to the work of algorithms in detecting new planets.

“It’s actually hard to write code that can go through a million light curves and identify single transit events reliably,” the University of California, Riverside’s Paul Dalba said. A single transit event is when the planet passes in front of the star from our point of view, whereas computer algorithms used search for planets by identifying multiple transit events from a single star.

“This is one area where humans are still beating code”, Dr Dalba said.

A study based on the research was published in the Astronomical Journal last Thursday.