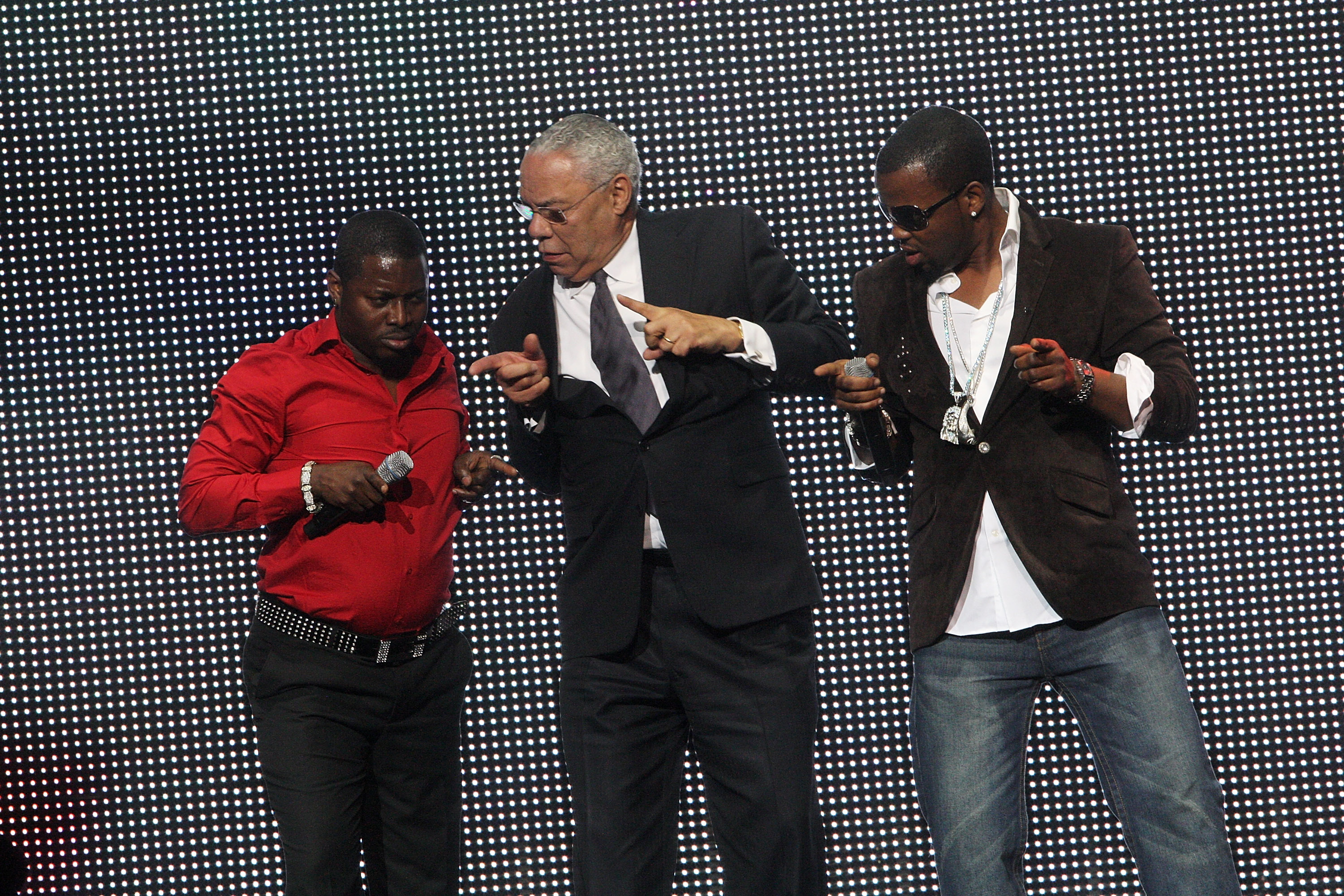

Lagos, Nigeria – On October 14, 2008, the former US Secretary of State Colin Powell joined Nigerian singer Olu Maintain on stage at the Africa Rising Festival in London to dance to Yahooze, arguably the hottest record out of Nigeria at the time. The dance racked up headlines on both sides of the Atlantic.

“He traded statecraft for stagecraft,” Foreign Policy’s David Kenner wrote.

It was also a seminal moment for the burgeoning but mesmerising genre known as Afrobeats, long before its global domination today. It also highlighted the significant role London would play as an amplifier of the genre that grew from the streets of Lagos.

In doing the Yahozee dance, Powell, one of the most idolised Black men in the world even after his October 2021 death from COVID-19, had unwittingly given a stamp of approval to an ode to flamboyance underwritten by internet fraud. The irony was highlighted by The Guardian two days later.

“The Nigerian hit is a celebration of that country’s most infamous export, advance-fee email fraud (sometimes called 419 fraud, after the relevant section of the Nigerian penal code),” the article read. “The perpetrators are known as “Yahoo Boys” after their email service provider of choice.”

That dance – as well as the song – remains pivotal in the genre’s story arc.

I think the biggest flex in the history of Nigerian Music was when Olu Maintain brought out The US Secretary of State on stage to come and dance to a song about fraud [Yahoozee].

It still keeps me up at night.

— ÀGBÀ (@Oli_Ekun) December 14, 2019

‘New millionaires’

In 2002, Nigeria had established the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC). One of its first high-profile cases was the trial of Emmanuel Nwude, a former bank executive who impersonated the central bank governor and defrauded a Brazilian bank of $242m.

Internet connectivity was on the rise and cybercafes were dotting small towns across many parts of Nigeria. Young men began trooping to cybercafes to send “Nigerian prince” letters and a culture of flamboyance from ill-gotten gains followed, so the EFCC had its hands full.

The arts, too, began to take note.

In 2005, Nollywood star actor Nkem Owoh released the satirical track I Go Chop Your Dollar, as the soundtrack to the movie The Master – playing an internet fraudster who dupes “greedy” white people. Authorities banned airplay of the song as its lyrics mirrored Nwude’s modus operandi.

And then there was Yahooze (a derivative of ‘Yahoo’) a comeback record for Olu Maintain (born Olumide Edwards Adegbulu) who had split from the popular boy band, Maintain, three years earlier. Unlike Owoh’s song, this was a celebration of materialistic culture.

After its October 2007 release, it quickly became a viral hit. Olu Maintain had struck a nerve, affected pop culture and resurrected his solo career; in 2008, Yahooze won the Song of the Year category at the Headies – Nigeria’s equivalent of the Grammys.

Industry insiders say it caught on quickly because its solid production and catchy juxtaposition of “hammer” (a Nigerian buzzword for huge cash inflow) with the car brand Hummer and “one million dollars” was an unabashed celebration of an ostentatious lifestyle that people could recognise.

“We were right at the peak of new millionaires, these new guys who were indoors all day but came out at night and painted the town red. That song captured the moment … [and] spoke to a lot of young people,” said Akinyemi Ayinoluwa, entertainment lawyer and partner at Lagos-based Hightower Solicitors & Advocates.

All the essentials of hip-hop culture were also present in the music video – flashy cars, bling jewellery, video vixens, a posse and expensive drinks.

“Our society celebrates and continues to celebrate money of all types and sources which makes things like internet fraud inevitable,” Obinna Agwu, a talent scout with Horus Music told Al Jazeera. “The artiste simply found grounds to connect with his audience.”

An enduring legacy

Olu Maintain has always denied that the song glorified internet fraud.

“When you create a body of art, people can misinterpret it the way they see fit … I cannot be responsible for how people interpret a work of art,” he told Nigerian daily Punch in 2018.

Nevertheless, it represented another chapter in the relationship between crime and music; the Italian-American mafia bankrolled many acts in its heyday, just as South American drug lords had ballads written for them and gangster exploits have been extolled in hip-hop.

Over the last decade, Yahoo Boys, too, have become grand patrons of the arts, setting up record labels and financing music projects in what is a multimillion-dollar industry.

“A lot of fraud money has definitely gone into (our music), from people who wanted to genuinely clean up their acts to people who really loved the music and needed to do something to get themselves out there because a conventional label is not going to give you a deal, they do not understand your vision,” said Agwu, the talent scout.

The music business is capital-intensive, and in Nigeria, where the industry still lacks adequate funding and infrastructure, upcoming artists, especially from inner-city areas, find it hard to access funds to boost their careers.

Many of these musicians, born and raised in slums, turn to internet fraudsters to help fund their ambition of being the next superstar. For many Yahoo Boys, it’s a win-win situation; bankrolling an artiste allows them to launder their money and boost notoriety via songs since artistes sing the praises of their benefactors.

“In Nigeria, we can say the Yahoo Boys or the internet fraudsters were the first set of people to get into talent, investing money in talent. And as a way to pay back, a lot of the talent who had benefactors who were internet scammers showed appreciation and reverence,” said Akinyemi Ayinoluwa, the lawyer.

In May 2019, Nigerian rapper Naira Marley was arrested by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) a day after he released the video to the controversial single Am I A Yahoo Boy?

The song was a follow-up to Naira Marley’s argument that internet fraudsters positively affect the Nigerian economy. He has since been released but the case continues to move labourously through Nigeria’s notoriously slow legal system.

In the meantime, pro-fraud songs are still prevalent despite the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation’s hard stance against them. In October 2021, an emerging act Steven Adeoye released a single Ali, about a boy who dumps school for the world of crime and becomes successful. It went on to be a hit single without any radio or TV play.

With unemployment still high among young people, many Nigerian singers will continue to sing about the realities of life, industry insiders say.

Afrobeats continues to announce itself on the global stage; in January 2021, Nigerian singer Burna Boy, arguably the foremost exponent of Afrobeats to the world, won the Best Global Music Album at the Grammys.

On his social media accounts, footage of the dazzling jewellery around his neck and of his assortment of luxurious cars are symbolic reminders of that connection to hip-hop and the grandiose spending associated with both genres.

But it is to the credit of Yahooze, the song that lit up the scene nearly two decades ago and Olu Maintain, no longer an in-demand act, that extravagance first became an accompanying export to Nigerian music.