Chances are, you have seen photographs taken by Bill Taub.

As NASA's first senior photographer, Taub was there to capture the start of the United States' human spaceflight program. Sixty-two years ago this week, it was Taub who was behind the camera as Alan Shepard climbed aboard his Mercury spacecraft "Freedom 7" to become the first American to launch into space.

Those photos, taken on May 5, 1961, have been published countless times over during the past six decades.

Related: Facts about Project Mercury, America's 1st crewed space program

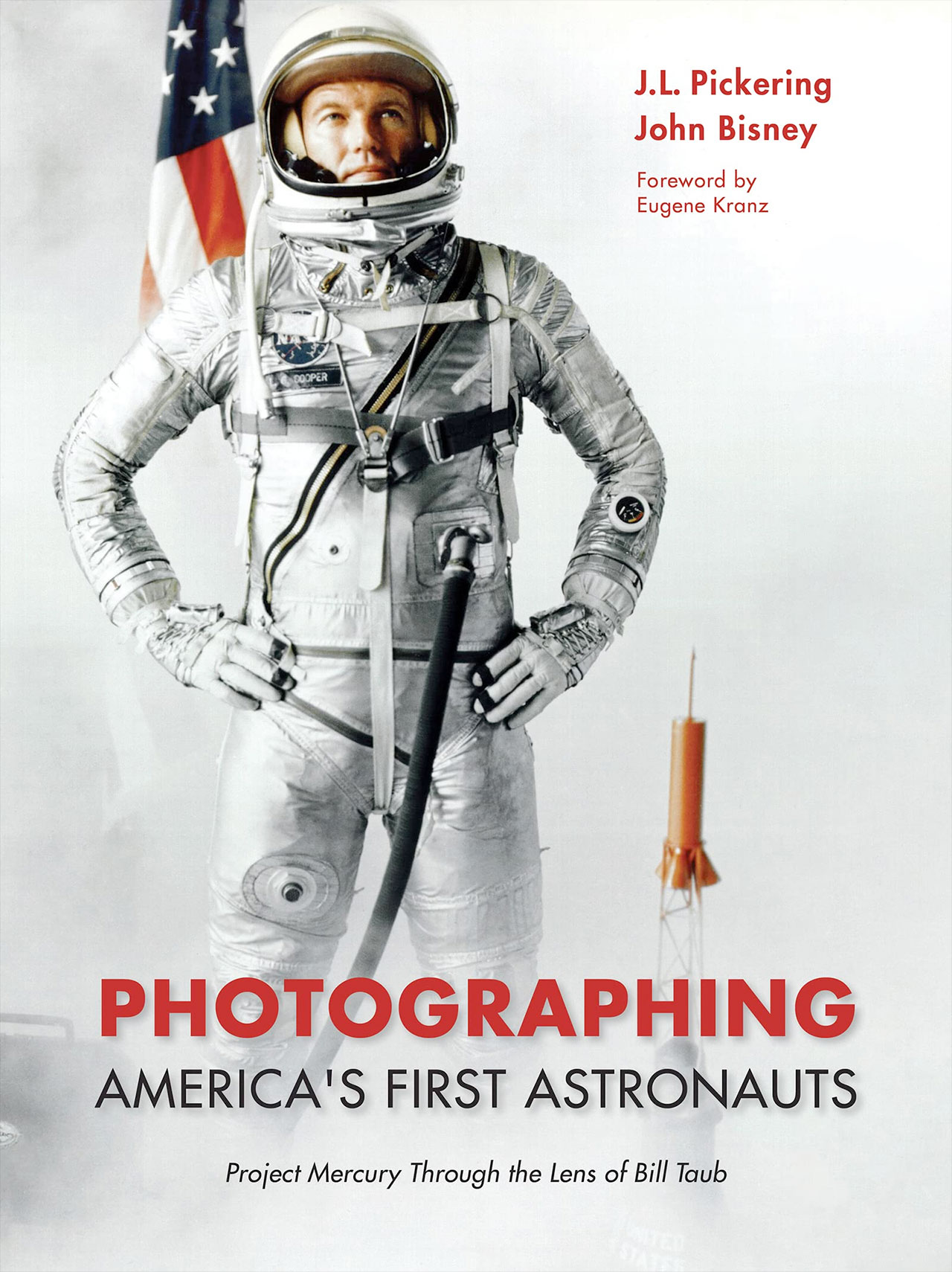

But as iconic as some of Taub's images are, it is only now that the public is getting to see the full extent of his work. Photo historian J.L. Pickering and journalist John Bisney uncover that unseen legacy in "Photographing America's First Astronauts: Project Mercury Through the Lens of Bill Taub," as published by Purdue University Press on Monday (May 1).

"I had corresponded with Bill regularly in the 1990s, and John and I visited him in retirement," said Pickering, describing how he and Bisney gained access to Taub's photos. "A couple of years after he had passed [in 2010], Bill's daughter and son-in-law were trying to organize his archives when they came across some of my letters to Bill. They promptly phoned me, and I was on the road to their house a week later. The Taub collection revealed more images from Mercury than I could ever have imagined."

"When J.L. began sharing the material with me, I was amazed," added Bisney. "After 60 years, you feel confident you've seen all the good Mercury photos, so this was just stunning."

collectSPACE (cS) exchanged emails with Pickering and Bisney to learn more about Taub and "Photographing America's First Astronauts."

cS: How does the collection of photos in "Photographing America's First Astronauts" compare or differ from your previous book about the Mercury program imagery ("Spaceshots and Snapshots of Projects Mercury and Gemini")? If readers already own a copy of that book, why should they buy this one, too?

Pickering: Simple answer — there's no duplication! Although many of the photos in "Spaceshots" were also by Bill, his archives have provided completely new material, and a lot of it.

Bisney: The Mercury section of "Snapshots" was 80 pages total; our new book is more than three times longer. And we cut about 75 additional images we loved, but would have made it too long for most publishers, including Purdue.

cS: What is it about Taub's photography that set his photos apart from others and therefore merited its own book?

Pickering: Obviously, a big part of that answer is access. As NASA's first staff photographer, Bill had essentially unlimited access to the Mercury astronauts. It's true that LIFE magazine featured far more family photos, but Bill was constantly around the astronauts, traveled with them and photographed them "in the office" on a daily basis.

Bisney: Right. It's his behind-the-scenes opportunities only he had. It's also apparent that the astronauts and others became quite comfortable around him.

Related: The Mercury 7 astronauts: NASA's 1st space travelers

cS: J.L., you mention LIFE. If people are aware of a photographer's name associated with the Mercury astronauts, they probably know LIFE magazine photographer Ralph Morse. Why do you think Bill Taub is not as well, if not better known?

Pickering: LIFE magazine was a big part of the American landscape back in the Mercury era. Ralph Morse received credit for his work via the pages of LIFE. On the other hand, Bill's images also became well-known around the world, but NASA did not credit him very often.

Bisney: Morse had the advantage when it came to notoriety simply because of his long association with LIFE, which had a readership of nine million. His credit appeared in the magazine for 30 years for his photos ranging from World War II to sports. Bill, on the other hand, as a government employee, worked in anonymity; yet he produced many more space-related photos than Morse.

cS: How much of the book covers what you found in the Taub archives? Are there still, for example, hundreds of more never-before-seen photos waiting to see the light of day, or does the book contain most of what he had saved?

Pickering: I would say two-thirds of the material is centered around Mercury. The rest consists of Gemini and Apollo photos, as well as some exceptional images of President Kennedy and President Johnson during their visits to NASA facilities. The material also includes some new views of Kennedy at Rice University.

Other highlights include astronaut jungle survival training images, Apollo 11 and Apollo 13 world tour images, and some nice Apollo training and mission preparation material. There is certainly enough material for more books!

cS: Did you learn anything new about the Mercury program or the astronauts through the Taub photographs? Was there anything surprising in what the photos captured?

Bisney: Yes, writing the captions is always a learning experience, especially the technical details.

We were able to disprove (through associated research), for example, a claim that the astronauts had witnessed a rocket explode on their first visit to Cape Canaveral. The photos [also] reveal for the first time that Alan Shepard piloted the KC-135 (for a while) returning him to Florida from Grand Bahama Island after his mission, which was assigned to Gen. Curtis LeMay!

We also see some astronauts and even their doctors smoking.

Pickering: You certainly come away with the feeling that the team operated like a close-knit family. Bill's photos also provide the best views inside the NASA medical clinics on Grand Bahama Island and Grand Turk, and the astronaut crew quarters at the Cape in Hangar S. All were off-limits to other photographers.

cS: Do you each have a favorite photo from the book?

Pickering: My favorite images are those that show the Redstone rocket at night on Pad 5. There is something magical about seeing the technicians hovering around the fueled rocket — a real man vs. machine tableau.

I will also add that there are many favorites of Gus Grissom. NASA released relatively few images from [America's second human spaceflight, the] Mercury-Redstone 4 mission, so it was great that Bill had retained so many images from that flight, and we were able to share so many in the book.

Bisney: I have several! But you asked about one, so I'd pick a full-page informal color photo of Bill with Alan Shepard in the white room at the Redstone launch pad.

Bill has one of his cameras around his neck; and while Shepard was fairly well-known as one of the seven astronauts, he hadn't flown in space yet. Both are young men pausing for a candid shot, not fully aware of the history they would both soon experience.

cS: What do you hope readers take away from seeing and reading about Taub's work in "Photographing America's First Astronauts"? Are there lessons that NASA should be heeding as it considers the photography needs for its Artemis program going forward?

Pickering: Bill did a wonderful job of taking photos that emphasized the human aspect of the program. Rarely were there images of hardware that did not include a technician or astronaut nearby. The people who made it happen should always be the primary focus.

Bisney: I hope readers better realize what an amazing accomplishment Mercury was at the time, and how much had to be done behind the scenes. It took more than four-and-a-half years and involved two million people from government and industry, and it was all done in the analog world of slide rules, typewriters and telephones.

I agree that one lesson for NASA photographers moving forward is to focus on people over technology.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2023 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.