Between March 2020 and June 2022, families in Toronto experienced some of the longest lockdowns in the world. Ontario schools closed for in-person learning for over 27 weeks, longer than any other province or territory, and government restrictions on public spaces lasted for months. Parents were left to figure out how to manage work, child care and virtual school.

We interviewed mothers of young children to reflect on how they managed their children’s screen media practices during this tumultuous time.

Our study is part of a larger collaborative research study, with researchers in Australia, the United States, China, Colombia, South Korea and the United Kingdom.

Children’s experiences of media consumption and production can vary enormously depending on their context, for example, due to government regulations or socio-economic differences.

Our interviews suggest there is never-ending pressure on mothers to negotiate kids’ technology use. Mothers need support managing these new realities.

Constant re-negotiation of media use

Between January and July 2022, we interviewed 15 mothers in the Greater Toronto Area over Zoom. We recruited parents and caregivers through 10 neighbourhood parenting groups on Facebook. Only mothers responded. Participants had children between the ages of four to 12, with people based in downtown and midtown Toronto and North York, as well as Burlington and Niagara.

All mothers were in two-parent families, although one was solo parenting with the other parent overseas. Most were middle class. When asked to self-identify racial and ethnic backgrounds of both parents, a range of answers included southeast Asian, Chinese, Jewish, white, Chinese Canadian, Scottish, “born in India now Canadian” and Canadian.

Mothers shared that for most of the pandemic, they were reassessing and re-negotiating their children’s technology use. Negotiations were focused on screen time and home spaces where children used technology.

These negotiations and decisions were loaded with moral implications. They were also refracted through families’ values and practices, mixed with anxieties about children as future adults — and nostalgia for mothers’ own childhoods in less technologically complex times.

Read more: Nostalgia for childhoods of the past overlooks children’s experiences today

Balancing time

Mothers’ reflections on screen time were messy, complicated and sometimes contradictory.

For example, mothers constructed some screen time as “good” if it involved skill-building, educational opportunities, communication with friends or family or was a family activity (like watching movies or playing with video consoles or online games together).

Mothers positioned video games played alone or with peers as more concerning. They worried about isolation and addiction. Families adopted strategies for monitoring screen time by using timers, scheduling screen time and limiting children’s access to WiFi or devices.

Guilt for letting someone down

Several mothers cited pediatricians’ and researchers’ recommendations around screen time, and many felt that these guidelines placed immense pressure and expectations on them as parents during the pandemic. While they cited these guidelines as ideal, following them was more complicated.

One mother stated: “I’m pretty sure we’ve broken all those rules.” She described parenting during the pandemic as “an impossible balance” of being in a “survival mode” where sometimes “the TV is [the] parent now, because I have to get work done so that I can, you know, generate an income.”

This increased presence of technology in the home and her children’s increased screen time was connected to “feelings of guilt” of either letting her kids down by not being able to interact with them, or letting work down by “ignoring tasks.”

Balancing space

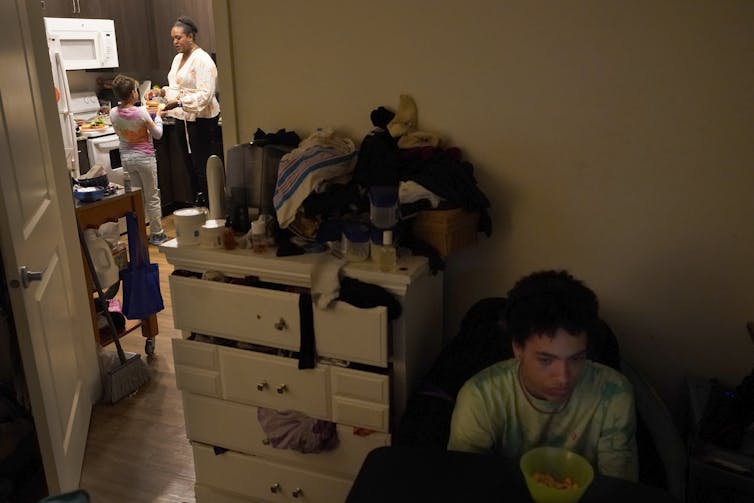

It was not just that time on screens was an “impossible balance” but which screens were being used, where and for what (leisure or school). Families’ domestic spaces changed drastically with the lockdowns.

Open-concept houses made it easier to see what kids were doing with technology for leisure, but was distracting when kids and parents were trying to work and learn from home.

Parents who let their kids use the technology in the bedrooms found this allowed more focus for both the kids during school time and parents during the workday. However, this arrangement made it difficult to know what children were really doing online.

It took a toll

For some, reliable WiFi access wasn’t available in all spaces in the home, and voice-assisted technology such as Alexa meant the digital encroached into spaces that parents had previously designated as tech free.

With online school, many mothers found they had to sit near their children to keep them focused and help with the technology. This was even more challenging for those who had two or more young children in school.

One mother described supporting two children online as constantly “ping ponging” between them. Trying to work from home while supporting children took a toll. Many mothers described feeling frustrated as short lockdowns morphed into long months with no sense of returning to normal.

Some parents were able to transcend the school-home binary in a way that they were never able to before. These parents who closely supervised and supported their children with online school had a much greater sense of classroom dynamics between teachers, students and the curriculum.

Read more: Parent-teacher relations were both strained and strengthened by the COVID-19 pandemic

Tech use changed a lot for families

As the pandemic wore on, decisions and negotiations around screen time and where that screen time happened in the home were ongoing, and perhaps impossible to get completely “right.”

Technology use changed a lot for families during the pandemic. Some children were introduced to technology all together, as families got new devices, platforms and apps. Instead of one family computer for example, with online school, each child had access to their own device. This affected how mothers managed children’s and families’ time and space.

Mothers’ decisions around children’s screen media use are wrapped in worries about being a “good parent,” concerns around children’s childhood and futures and work-from-home realities.

There is no returning to the pre-pandemic realities of tech in the home. Many kids have new devices, spaces to use those devices — and expectations to use technology for activities that previously were offline.

Must accept shared responsibility

It’s not enough to think our society can manage families’ changed home tech use and the burden of responsibility it brings to mothers just by having medical professionals offer screen time guidelines. One-size-fits-all solutions like screen time guidelines fail to take into account the complexity of technology in families.

We need broader discussions that include the responsibilities of social media and educational technology companies, schools and policymakers, to name a few, to support families in navigating these new realities.

Natalie Coulter received funding from York University Liberal Arts and Professional Studies Minor Research Grant.

Lindsay C. Sheppard received funding from York University Liberal Arts and Professional Studies Minor Research Grant.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.