What you need to know

- In an appellate court ruling this week, net neutrality rules were struck down in a massive blow to regulation.

- The court decided that the FCC didn't have the authority to impose net neutrality rules on ISPs, disagreeing with the agency's interpretation of the Telecommunications Act.

- The decision hampers executive branch agencies' ability to regulate big tech companies, and precedent could be applied to hot-button issues like right-to-repair.

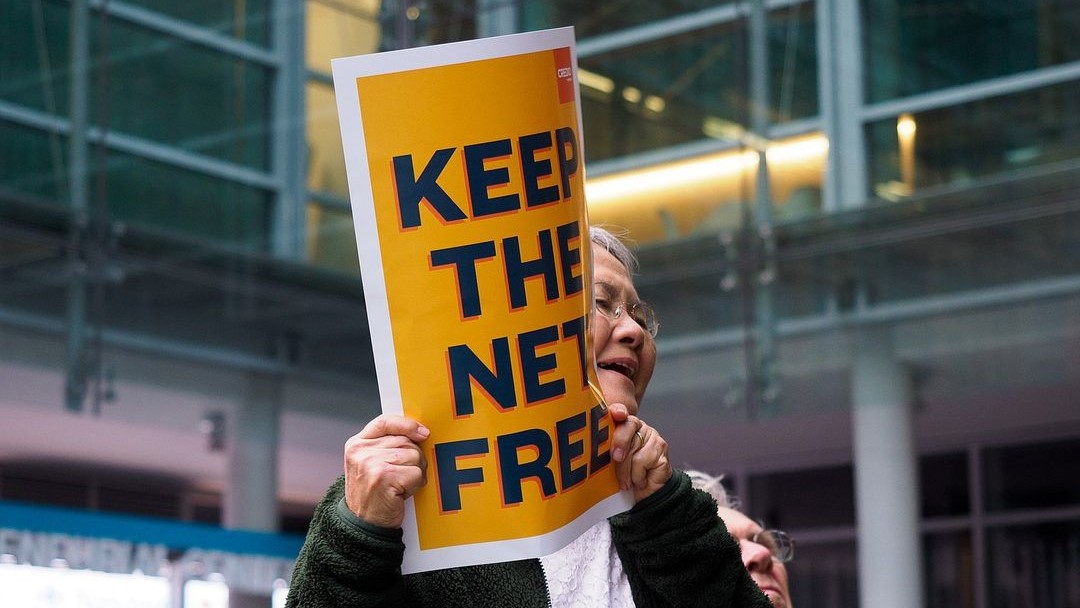

Following the Biden administration's brief revival of net neutrality, a federal appeals court decided the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) does not have the authority to impose those rules on internet service providers (ISPs). The controversial set of net neutrality rules have been the topic of fierce debates for nearly a decade, and the court's ruling means they may be gone for good. More importantly, the decision sets further precedent that limits federal agencies' ability to regulate big tech, in aspects such as right-to-repair.

For those unfamiliar, net neutrality was a set of rules that essentially forced ISPs to treat all internet traffic equally. It didn't matter which website you wanted to reach or where you were located — ISPs couldn't give certain domains preference over another.

Why would an ISP want to do that? Comcast, for example, owns Xfinity, which represents 40% of all broadband internet subscriptions and is the nation-leading ISP by far, according to Statista. It also owns NBCUniversal, which hosts streaming service Peacock. Without net neutrality, Comcast could — in theory — prioritize Peacock streams over Netflix streams to put its own interests ahead of those of its subscribers.

So, that's the argument for net neutrality. The argument against net neutrality is that it will result in customers paying more for internet service. Think about it: If ISPs were allowed to slow down internet speeds of certain sites, it could demand that the companies hosting those sites pay for better preference. Without net neutrality, deals with big-name sites serve as a supplemental revenue sources for ISPs — revenue that would otherwise be attained by charging average people more.

For years, the FCC struggled to correctly classify ISPs. It started by calling them "information services" in 2005, which would not give the FCC authority to impose regulations upon them. Then, it shifted course in 2010, passing the Open Internet Order. Broadband providers sued to block the FCC's first stab at net neutrality rules and were successful, because the courts decided the FCC could only regulate "common carriers," like airlines, railroads, and some telecom companies.

It was settled — or so we thought. In 2015, then-President Barack Obama gave the green light for the FCC to reclassify broadband internet providers as common carriers. Thus, giving the FCC the authority to impose net neutrality rules as they are known today. Once again, it seemed settled, until the FCC decided to roll back net neutrality under then-President Trump in 2017.

Finally, net neutrality got a second chance under President Biden, although it immediately faced grim legal challenges. That brings us to the present, when a federal appeals court struck down net neutrality seemingly for good with the help of newly-minted Supreme Court precedent.

Regardless of what you think about net neutrality, this decision is monumental. It's a confirmation of what was expected when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a legal principle established through precedent with the case Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) in 1984. The practice became known as Chevron deference, and it essentially meant that courts would give deference to expert regulatory agencies' interpretation of laws when deciding cases.

Why would the courts give deference to executive branch agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or FCC? The reasoning was twofold. For one, these cases usually concerned complex issues that the average federal judge was likely not an expert on, whereas regulator agencies are the authoritative subject matter experts in their respective fields.

Additionally, there was the thought that executive branch agencies were best fit to make major policy decisions because they could be held accountable by voters — we saw this in practice as net neutrality tumbled through the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations.

When the Supreme Court killed the idea of Chevron deference last year, it gave courts nationwide the precedent to favor their own interpretation of the laws rather than those of regulatory agencies.

That's precisely how we got here. The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals didn't agree with the FCC's classification of ISPs as common carriers, and didn't think the FCC had the authority to impose net neutrality rules. For the first time in decades, the court's opinion held more weight than the agencies' opinion.

"Unlike past challenges that the D.C. Circuit considered under Chevron, we no longer afford deference to the FCC’s reading of the statute," the judges wrote in their decision. "We acknowledge that the workings of the Internet are complicated and dynamic, and that the FCC has significant expertise in overseeing ‘this technical and complex area," they continue, adding that the agency's interpretation "cannot be used to overwrite the plain meaning of the statute."

The decision is not only a massive blow to net neutrality, but also a hit to big tech regulation in general. If executive branch agencies — such as the FCC or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) or the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), can't reign in tech companies without explicit laws giving them the authority to do so — progress may stall.

That reality puts even more pressure on U.S. Congress to enact laws that regulate big tech, which can withstand judicial scrutiny.

"Consumers across the country have told us again and again that they want an internet that is fast, open, and fair," said Jessica Rosenworcel, the FCC chair, in a statement. "With this decision it is clear that Congress now needs to heed their call, take up the charge for net neutrality, and put open internet principles in federal law."

If you've followed hot-button technology policy topics of late — think net neutrality, right-to-repair, antitrust, and interoperability — you'll know just how hard it is to get Congress to agree on these issues. Now that the Chevron deference is gone, and the new precedent has been applied to big tech for the first time, agencies will have limited leeway to regulate these conglomerates. Only time will tell how that, plus the transition to the Trump administration later this month, will affect the real progress made in big tech regulation over the last few years.