History wars are nothing new — whether in India or almost any country in the world. In recent years, two of the most prominent figures to be caught in the crosshairs of these ideologically-driven skirmishes have been Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel. To his detractors, Nehru’s place in history has been overvalued, whereas Patel yet to be given his due. Had Patel, with his pro-market ideology and superior organisational skills, become India’s first prime minister, the country’s evolution as an independent country would have been radically different.

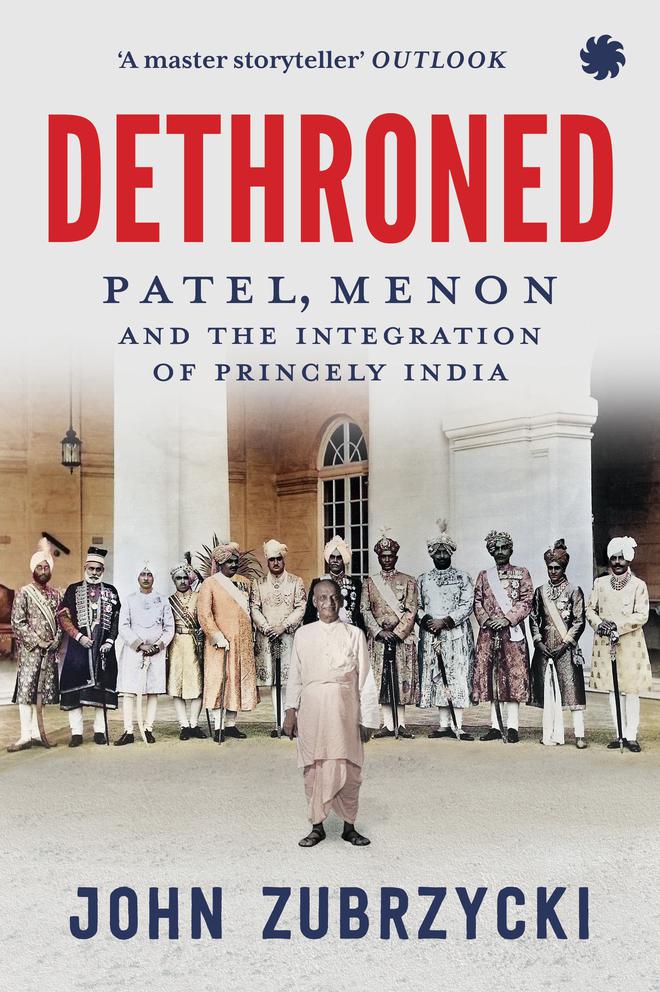

In my recent book Dethroned, I examine the critical role of the 562 princely states in the transfer of power in 1947. That India narrowly averted being ‘Balkanised’ if these states opted for independence or joined Pakistan’s has more to do with Patel’s powers of persuasion than Nehru’s charisma, but the remarkable feat also highlights their strengths and weaknesses — and the rivalry that existed between them.

When it came to the princely states, the two men were fundamentally in accord. To Nehru, they were ‘sinks of reaction and incompetence and unrestrained autocratic power, sometimes exercised by vicious and degraded individuals’. To Patel, their rulers were ‘worthless … sycophants’, who their slave-like subjects had ‘a right to dethrone’.

Yet their approach towards them differed greatly. Had Nehru been put in charge of the States Department when it was formed in late June 1947, his visceral hatred of the princes would have sabotaged any hope of seeing a majority accede to India. When in April that year he warned that any state that did not accede would be treated as hostile, many princes took it as a sign that there was no future for them in a Congress-led India.

Patel persuaded the princes

Patel, who took on the role of States Minister, employed a more diplomatic and pragmatic approach, appealing to the princes’ proud, glorious past, when their ancestors ‘had played highly patriotic roles in the defence of their family honour and the freedom of their land’. Working strategically, he cultivated close links with influential rulers who would then convince their fellow princes of the benefits of joining the Indian Union.

Together with V.P. Menon, his deputy in the States Department, and the viceroy Louis Mountbatten, he persuaded hundreds of rulers to sign Instruments of Accession ceding defence, external affairs and communications to India. By August 15, just a handful of states had refused to accede.

This difference in style — Nehru’s inability to rise above his beliefs, Patel’s profound pragmatism in the service of his nation — would show up in frequent clashes. The two men argued bitterly, with Nehru accusing Patel of communalism. The prime minister’s reluctance to use force to deal with threats to India’s territorial integrity thrown up by Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan, the tribal invasion of Kashmir, and Hyderabad’s declaration of independence, infuriated his deputy.

In late September 1947, Nehru demanded that Patel restrain the Hindu maharajas of Bharatpur and Alwar who were suspected of organising pogroms against their minority Meo Muslim populations. His requests were ignored. When Patel did finally respond, he cautioned against taking action, prompting Nehru to send his principal private secretary, H.V.R. Iyengar, to get a first-hand report on the communal situation. When Patel protested, Nehru threatened to resign, accusing his deputy of ‘restricting his freedom’. Patel refuted the charge, but then proceeded to countermand the prime minister by ordering all Meos to be evacuated to Pakistan.

Kashmir and Pakistan

When Junagadh’s reclusive, canine-obsessed ruler Mahabat Khan announced his state’s accession to Pakistan, Patel immediately recognised the implications. If India accepted Khan’s legal right to decide which dominion to join, it would set a precedent for another Muslim prince ruling a Hindu-majority state, namely, Hyderabad. Not challenging the accession would give Pakistan the right to object to the Hindu ruler of Muslim-dominated Kashmir opting for India.

To avert such scenarios, Patel insisted that India intervene militarily. This time, it was his turn to threaten to resign, accusing Nehru of a failure to stand up to the British officers commanding the armies of both dominions who feared that such intervention would lead to an all-out war. He also clashed with the prime minister over his offer to hold a plebiscite in Junagadh, calling it ‘unnecessary and uncalled for’.

No sooner had the Junagadh crisis been resolved, after Khan fled to Karachi, a much more serious one erupted in Kashmir, where Maharaja Hari Singh refused to accede to either India or Pakistan.

For Nehru, there was never any question that his ancestral home belonged to India but when it came to repelling thousands of tribal militias swarming towards Srinagar, he equivocated. At a defence committee meeting convened on October 26 to determine a response to the invasion, Col. Sam Manekshaw, Chief of Army Staff, witnessed Patel angrily demanding that Nehru declare whether he wanted to keep Kashmir or give it away. ‘He [Nehru] said, “Of course, I want Kashmir.” Then he [Patel] said, “Please give your orders.” And before he could say anything, Sardar Patel turned to me and said, “You have got your orders.”’

When it came to Hyderabad, Patel initially took a hands-off approach, preferring Nehru to deal with the recalcitrant Nizam, Osman Ali Khan. But as the crisis dragged on, it was Patel who took the initiative to prepare for a military invasion to put an end to the state’s bid for independence.

Once again, Nehru opposed using force to end the crisis. Tensions came to a head at a meeting in September 1948, where Nehru lashed out at Patel calling him a ‘complete communalist’. Patel sat in silence as Nehru continued his harangue and then walked out of the room. The episode so shocked him that he had a heart palpitation and had to be put on oxygen.

Privy purses for the princes

Despite Patel’s antipathy towards the princes, he was determined to honour his promises to them by enshrining their privy purses, privileges and dignities in the Constitution, declaring that this was a small price to pay for sacrifices they had made. A socialist to the core, Nehru baulked at the expenditure of public money on privy purses in perpetuity while lakhs of Indians were starving.

Nehru would ultimately honour Patel’s promises, giving the princes a respite until December 1971, when his daughter Indira Gandhi used her majority to pass a bill in the Lok Sabha de-recognising the rulers and abolishing their privy purses. Had Nehru been alive, he would have applauded the move, but not Patel who would have viewed her actions as a final betrayal.

Despite their clashes and threats of resignation, Patel and Nehru also managed to work together. Patel’s superiority as a tactician ultimately saved India from fragmenting, enabling Nehru, for better or worse, to pursue his own vision of a socialist, secular and non-aligned nation. The result was the Indian map (largely) as we know it today. Would they have managed to retain their often-volatile working relationship had Patel not died in 1950? One can only speculate.

The writer’s latest book is ‘Dethroned: Patel, Menon and the Integration of Princely India’, published by Juggernaut, July 2023.