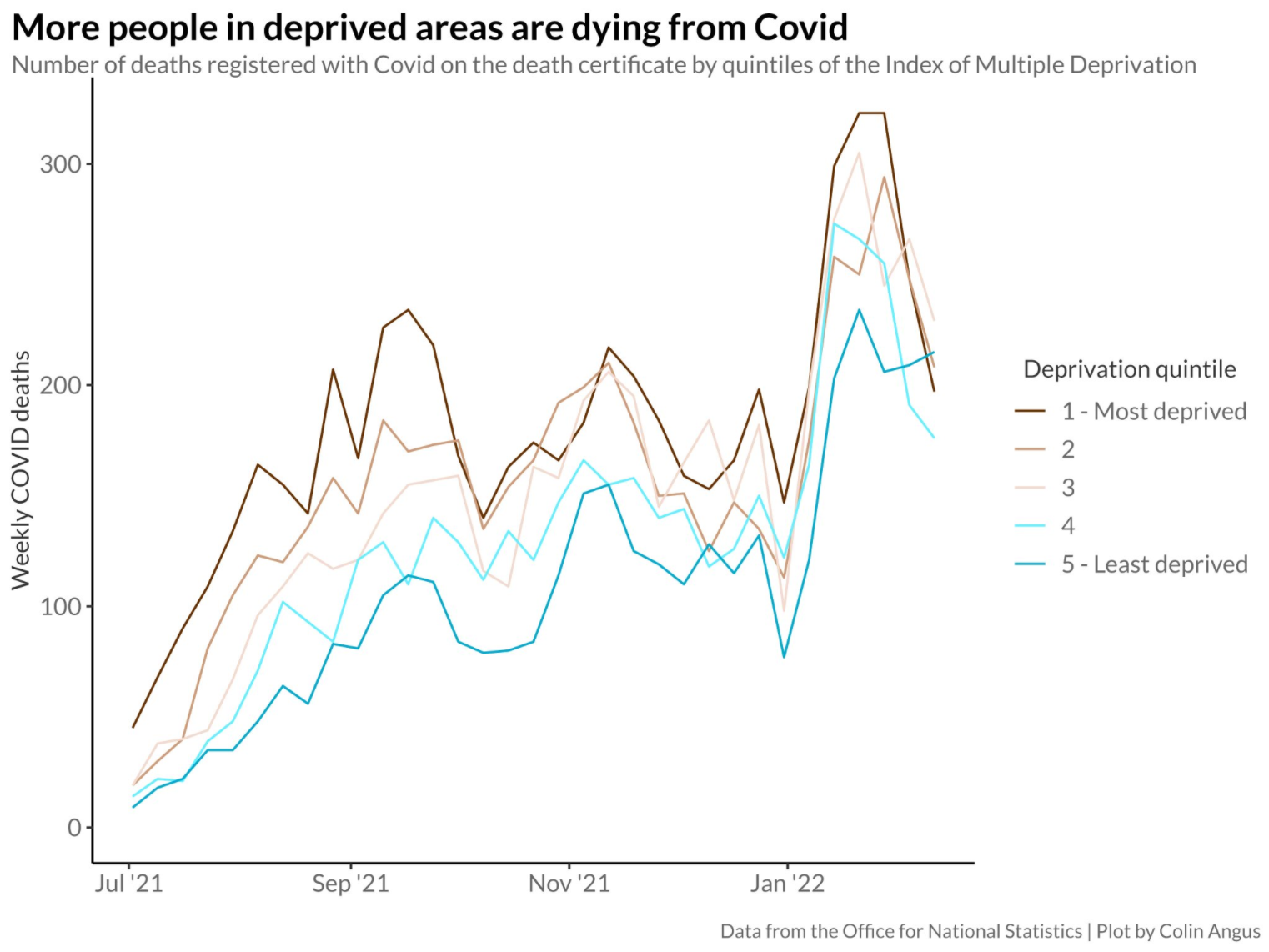

At least 30 per cent more coronavirus deaths have occurred in the most deprived areas of England since the turn of the year, data shows, reinforcing concern that the poorest communities will carry the greatest burden of disease under the government’s plans for “living with Covid”.

Of the 7,053 deaths registered in the six weeks after 1 January, 1,589 (22.5 per cent) were from the most deprived 20 per cent of the country, compared to 1,188 (16.8 per cent) in the least deprived 20 per cent.

Ministers have been warned that these disparities will only widen as the government scales back free testing and mandated isolation, and removes sick payments for those ill with Covid.

Such figures, which are only available to 11 February, are likely to underestimate the scale of Covid inequalities: the most deprived areas in England tend to be younger in age, while the least deprived have an older population, who are more vulnerable to coronavirus. Despite this, the poorest parts of the country still account for a higher proportion of deaths.

Labour’s Wes Streeting, the shadow health secretary, said the pandemic should have served as “the wake-up call we need to confront these shocking inequalities”.

Instead, he warned, the Conservatives “are pricing people out of acting responsibly, by removing sick pay and ending free testing. Free tests can’t go on forever and we would review them before the summer, but removing them now is like being 2-1 up with 10 minutes to go and taking off your best defender.”

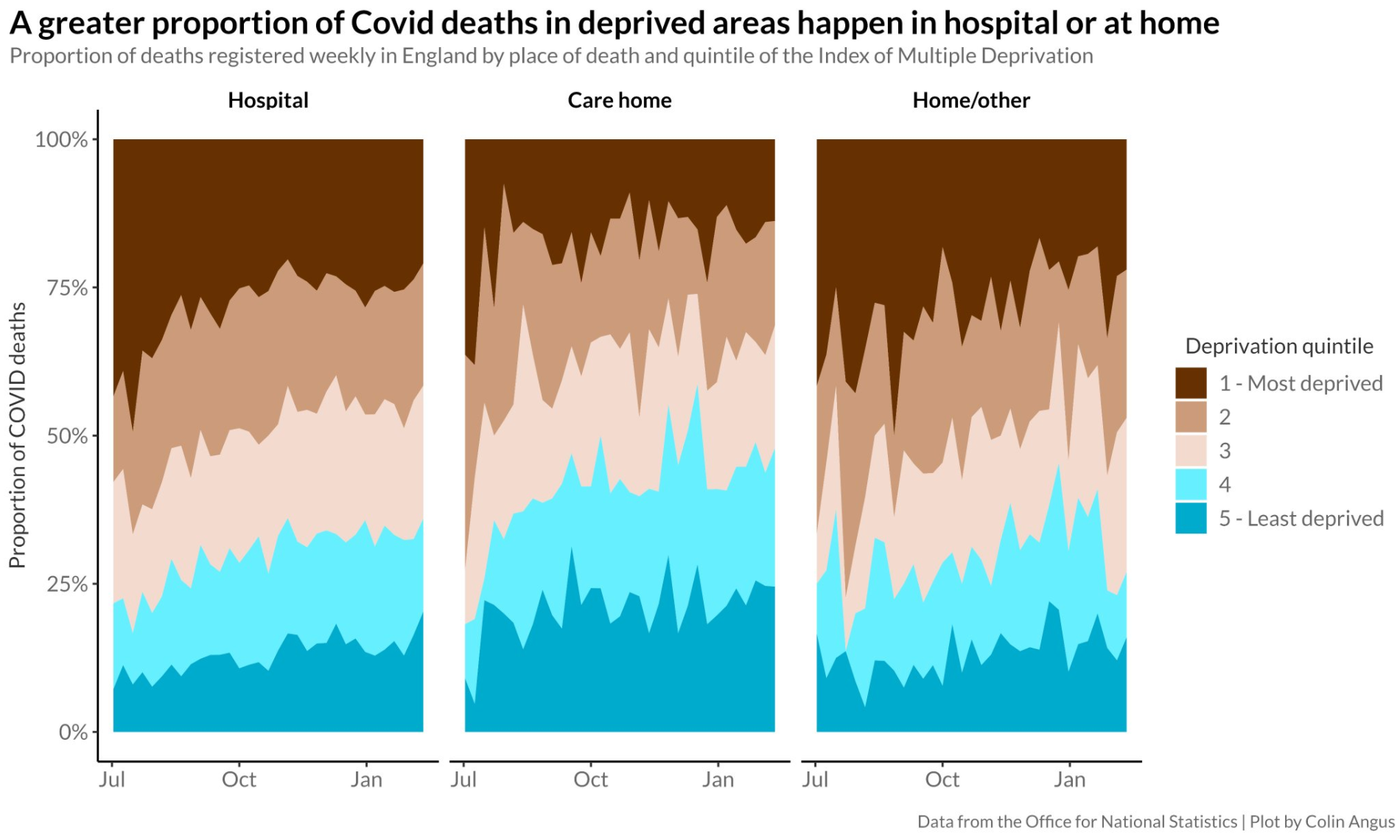

Analysis conducted by Colin Angus, a senior research fellow and health inequalities modeller at the University of Sheffield, shows that a majority of hospital and at-home deaths – close to 25 per cent, respectively – are occurring in the most deprived parts of England.

In contrast, these areas account for a far lower proportion of care home deaths, the modelling shows, due to their younger populations.

The Health Foundation said the figures were “concerning and represent a warning sign that the virus may continue to have a disproportionate impact” in the weeks and months to come, while Mr Angus said the “inequalities we’ve seen in recent months reflect the situation with free mass testing and mandatory self-isolation”.

Removing both of these measures “may be a necessary step on the path to returning to normality”, he added, but doing so at a time when prevalence of Covid infections remains “extremely high” will have a greater impact on more deprived communities.

More than 2 million people were infected with coronavirus last week, the latest estimates from the Office for National Statistics show.

Legally, those in England who test positive for Covid are no longer required to self-isolate. Universal testing and contact tracing have ended, along with support payments for people infected with coronavirus who are unable to work.

Free Covid tests will remain available for some vulnerable groups, the government has said. During a meeting held between charities and Cabinet Office officials earlier this week, over-80s, care home residents and social care staff were all discussed as likely options, The Independent understands.

“However, nothing has been decided, and it’s likely to take a matter of weeks before official policy is set,” a source said.

In making it harder to access testing for the poorest, and removing self-isolation measures, it is “almost inevitable that infection rates will remain higher for longer” in England’s poorest neighbourhoods, said Mr Angus.

“It is extremely disappointing that, in spite of repeated warnings, the government have taken no action to address the lack of sick pay available to many people, particularly those on lower incomes, while self-isolating,” he added.

“Doing so would go some way to reducing the economic impact of high infection rates among communities who have already borne the brunt of the pandemic’s impact.”

Mr Streeting said: “Removing sick pay and ending free tests now is unfair and bad for public health.”