Those in the disability field have been expressing a sense of whiplash since Friday. Many had felt buoyed by reassurances from Bill Shorten, minister for the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), at the National Press Club the previous week that a reboot would ensure the scheme was “here to stay”. Yet a week later, the word from the National Cabinet meeting of state and territory leaders, was that NDIS growth would need to be constrained in order for the scheme to be sustainable.

An independent review of the NDIS, is due to report before October this year. Ahead of its findings, critics have been quick to pass judgement on the financial outlay of the NDIS without comprehending the significance of cutting spending on the lives of Australians with disability and their families.

But people with disability have been here before. Our recent research shows people’s wellbeing deteriorates when their supports are threatened. We need to learn from their experiences before putting them in that same position again.

Read more: Health and housing measures announced ahead of budget, and NDIS costs in first ministers' sights

Enormous investment

The NDIS provides funding for more than 550,000 Australian with permanent and severe disabilities to receive the services and supports they need. However, with the current budget at A$29.2 billion and estimated future costs at $60 billion per year it is consistently being raised as a budgetary concern.

Similarly, spending on the Disability Support Pension, which provides required income support for people with long-term disability, is at $18.3 billion per year. In total, these two schemes amount to a $47.5 billion a year investment into the wellbeing of Australians with disability and their families.

The previous government already implemented significant changes and reviews for those receiving the Disability Support Pension and also sought to introduce independent assessments for NDIS participants.

While independent assessments are off the table for the current government, participants undergo regular reviews of their plans. They have been undertaken annually but the National Cabinet announced multiyear plans will now be implemented.

People on the Disability Support Pension have also experienced the threat of losing support. In 2012, new impairment tables were brought in for them and in 2014 it was decided to review people under 35 who had been deemed eligible under the old impairment tables. Some later described how being under medical review proved particularly stressful and negatively impacted their health.

Read more: The NDIS is set for a reboot but we also need to reform disability services outside the scheme

What we looked at

Our new study based on anonymous administrative data on all welfare recipients and healthcare use has shown the medical review of Disability Support Pension recipients under 35 led to significant increases in GP and specialist visits. We wanted to investigate whether this was due to additional consultations to prove eligibility or from the need to manage the stress of the review process itself.

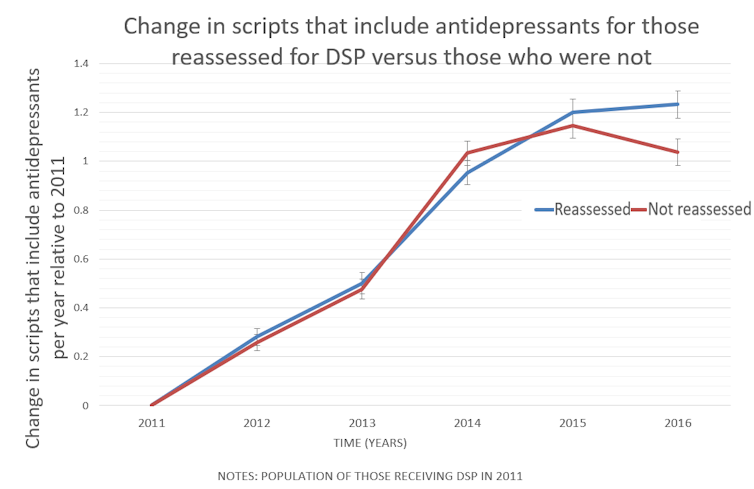

To investigate this, we looked at several types of medications and found that the group that includes antidepressants was the only one that increased for those targeted by the review. The increase was not driven by the few who stopped getting disability support, but by those who still received the Disability Support Pension after the review. This indicates the reassessment process itself contributed to poorer health.

Increased health-care use was likely just the tip of the iceberg, with many people experiencing mental distress as the result of the reassessment likely suffering in silence.

Taxpayers also contributed more than $4 million to cover the additional healthcare expenses incurred by the review, on top of the $21 million in government costs to conduct the reviews. These financial costs do not account for the additional time contacting Centrelink, finding healthcare professionals, attending visits and appealing the process. Such costs are not only borne by people with disabilities but also their carers, as well as the not-for-profit sector and other government sectors such as the judicial system. These efforts reduce the time people have available for finding work or contributing to society more broadly.

Read more: Inclusion means everyone: 5 disability attitude shifts to end violence, abuse and neglect

Caution ahead

Given these findings, a cautious approach to examining the cost of disability support is indicated. Medical Disability Support Pension reviews were eventually stopped and planned NDIS independent assessments were abandoned. But the spectre of these reviews and investigations remains.

The conclusions from NDIS independent review and the Royal Commission into Robodebt will help us understand the consequences of procedures that review entitlements and ensure that they do not harm Australians.

It is important we shift the focus from solely considering the NDIS and Disability Support Pensions in terms of their budgetary cost and measure their performance in terms of their impact on the health and wellbeing of people with a disability, their families and carers.

The NDIS is investing in a wellbeing measure for participants and the government has developed a Disability Strategy Outcomes Framework to “measure, track and report on how things are improving for people with disability”.

But as cost and growth scrutiny intensifies, policies must strike the right balance between the budgetary impact and the wellbeing of people with disabilities and their families.

Samia Badji receives funding from the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA). She has previously received funding from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Department of Social Services (DSS).

Anne Kavanagh receives funding from the National Health Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council and the Victorian and Commonwealth governments.

Dennis Petrie receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC), the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), WISE employment, the National Disability Insurance Agency and the World Health Organisation (WHO).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.