Growing up in Belgium, I’d hear the story of how my grandparents married during the Nazi occupation. It was not a time for celebrations, particularly for Jewish families like theirs. Naively, though, they thought marriage would protect them from being separated should they be deported. So in June 1942, they went to city hall with their loved ones – “decorated,” as my grandmother would say, with yellow stars.

Hearing that story as a child, I imagined them in dark clothes with shiny stars, each one a human Christmas tree – a celebratory image that only existed in my brain. Her most vivid memory of that day were the looks in people’s eyes: stares of curiosity, pity and contempt. The yellow star had transformed them, in onlookers’ eyes, from joyous newlyweds into miserable Jews.

Decades later, I completed a Ph.D. on the history of forcing Jewish people to wear a badge. My grandmother called to congratulate me – and, I soon understood, to unburden herself of a story she’d never told before.

When the Nazis issued the law forcing Jewish Belgians to wear a yellow star in May 1942, my grandmother’s future father-in-law declared that he would not wear it. The whole family tried to persuade him otherwise, fearing the consequences. But it was in vain, and in the end, my grandmother stitched the star on his coat.

I could hear her voice trembling on the phone as she told me she still could not forgive herself. Their wedding two weeks later would be the last time she saw him: He died in 1945 after being released from a transit camp and a detention home for elderly Jews, spending two years in terrible conditions.

Although the yellow badge has come to symbolize Nazi cruelty, it was not an original idea. For many centuries, communities throughout Europe had forced Jewish residents to mark themselves.

Yellow wheels and pointed hats

In lands under Muslim rule, non-Muslims had been required to wear identifying marks since the Pact of Umar, a ruling attributed to a seventh-century caliph, though scholars believe it originated later. These were usually a yellow belt, called “zunnar,” or a yellow turban.

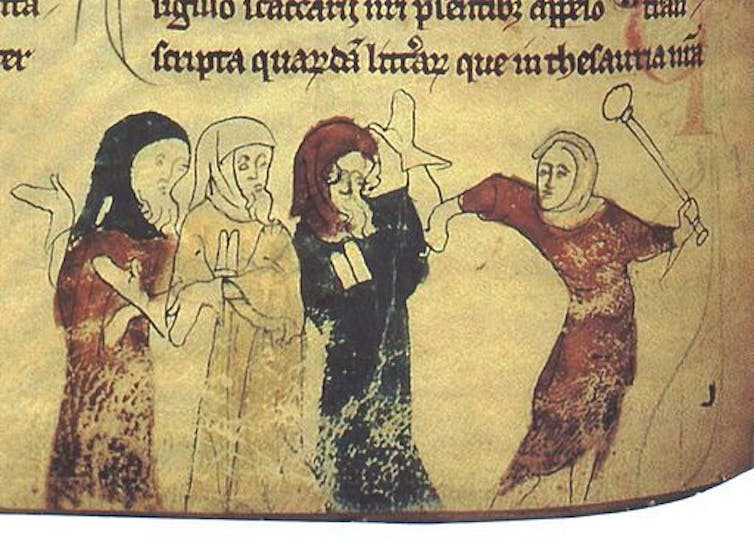

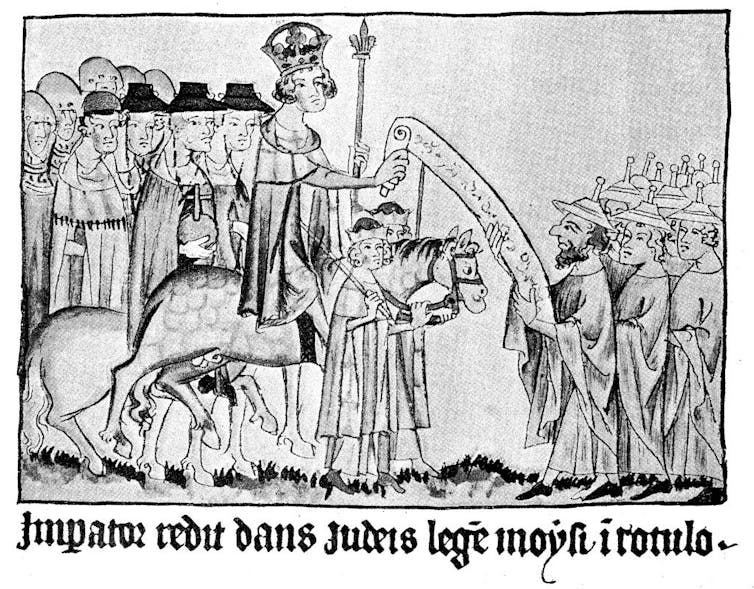

In Europe, forced markings for Jews and Muslims were introduced by Pope Innocent III at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. The pope explained that it was a means to prevent Christians from having sex with Jews and Muslims, thereby protecting society from “such prohibited intercourse.”

However, the pope did not specify how Jews’ or Muslims’ dress had to be different, resulting in various distinguishing signs. Ways to make Jews visible in the cities and towns of medieval Europe abounded: from yellow wheels in France, blue stripes in Sicily, yellow pointed hats in Germany and red capes in Hungary to white badges shaped like the Ten Commandments tablets in England. Since there were no large Muslim communities in Europe at the time, except for Spain, the regulation only applied to Jews in practice.

In northern Italy, Jews had to wear a yellow, round badge in the 15th century and a yellow hat in the 16th century. The reason typically given was that they were unrecognizable from the rest of the population. For Christian authorities, unmarked Jews were like gambling, drinking and prostitution: All represented the moral failings of Renaissance society and needed to be fixed.

Pretext for persecution

However, as I explain in my book, Jews were often arrested for not wearing the yellow badge or hat, sometimes while traveling away from home in places where no one knew them.

Clearly, then, Jews were recognizable from Christians in other ways. The true aim of forcing Jews to wear emblems was not merely to “identify” them, as authorities claimed, but to target them.

My research showed that laws imposing a badge or hat functioned as means to threaten and extort Jewish communities. Jews were willing to pay considerable sums to retract such laws or soften their provisions. For example, Jews requested exemptions for women, children or travelers. When communal negotiations failed, wealthy individual Jews tried to negotiate for themselves and their families.

Badge laws were frequently reissued, which has led scholars to conclude that their enforcement was inconsistent; after all, a legal directive that is steadily applied does not need to be reimposed. But with the risk of arrest and extortion hanging over the heads of Jewish communities, and their willingness to pay or negotiate to avoid these consequences, badge laws had adverse effects on Jewish life even when not enforced.

In the Duchy of Piedmont in modern-day Italy, for example, Jewish communities banded together to pay additional taxes, sometimes several times in the same year, to receive exemptions from wearing the Jewish badge. Although the Jews’ cohesion was remarkable, it had a high cost, as these communities ended up ruined and leaving the duchy.

When Italian Jews asked authorities to cancel or at least amend badge laws, they were not primarily worried about being recognized as Jews. The problem was being mocked or attacked. Violence had accompanied badge laws since their inception: Just a few years later, Pope Innocent III wrote to French bishops that they needed to take every possible measure to ensure that the badge did not expose the Jews to the “danger of loss of life.”

Yet harassment continued. Sometime in the 1560s, for example, the governor of Milan received a a letter from Lazarino Pugieto and Moyses Fereves, bankers from Genoa, explaining that bandits had robbed them after recognizing them as Jews. In 1572, Raffaele Carmini and Lazaro Levi, representatives of the communities of Pavia and Cremona, wrote that when Jews wore the yellow hat, youngsters attacked and insulted them. And in 1595, David Sacerdote, a successful musician from Monferrato, complained that he could not play with other musicians when wearing a yellow hat.

‘In the past, no one noticed me’

Centuries later, the yellow star had the same effect.

Max Jacob, a French-Jewish artist and poet, wrote of experiencing a vision of Christ, and he converted to Christianity in 1909. During the Nazi occupation of France, he was nonetheless classified as a Jew and forced to wear the yellow star.

In the prose poem “Love of the Neighbor,” he wrote about the deep shame he experienced.

“Who saw the toad cross the street?” he asked. No one had noticed it, despite his clownish, grimy appearance and weak leg. “In the past, no one noticed me in the street either,” Jacob added, “but now kids mock my yellow star. Happy toad! you do not have a yellow star.”

The Nazi context differed significantly from Renaissance Italy’s: There were no negotiations or exceptions, not even for large payments. But the mockery by children, the loss of status, and the shame remained.

Flora Cassen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.