“We are not extremists, we are not ultras, we are not hard or far right. These are the labels some people use against us, and these labels are wrong,” Dmytro Kotsyubaylo wants to stress at the base of his unit on Ukraine’s front line.

The young commander of the Pravy Sektor (Right Sector) unit points out that strenuous efforts have been made to keep out those who hold Nazi, fascist or racist views, and that this would remain the case if another conflict were to erupt and there was an urgent need for recruits.

Pravy Sektor is one of the most well-known and controversial armed groups to emerge from the fierce street clashes of the Maidan protests, which overthrew the government of Ukraine’s pro-Moscow president Viktor Yanukovych seven years ago.

The group’s fighters went on to play a prominent part in the conflict that followed against the separatists in the east, and became, in the process, figures of hate for their Ukrainian and Russian adversaries. For the first six months of the fighting, Pravy Sektor was one of the top three most frequently mentioned political groups in Russian media, and the organisation was banned in Moscow.

Pravy Sektor has also, it should be noted, faced fierce criticism within Ukraine for its hardline nationalist membership when it was formed, and for its militant activities, which have led to clashes with police.

In the current combustible crisis in Ukraine, with the threat of war looming and more than 100,000 Russian troops surrounding the border, Pravy Sektor continues to be held up as an organisation of dangerous bogeymen by the separatists and their backers in Moscow.

Earlier this week, a senior official of the Kremlin-backed breakaway Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) claimed that a group of Polish “mercenaries” had been identified preparing to carry out “terrorist and sabotage attacks”, and that they were working alongside Pravy Sektor fighters.

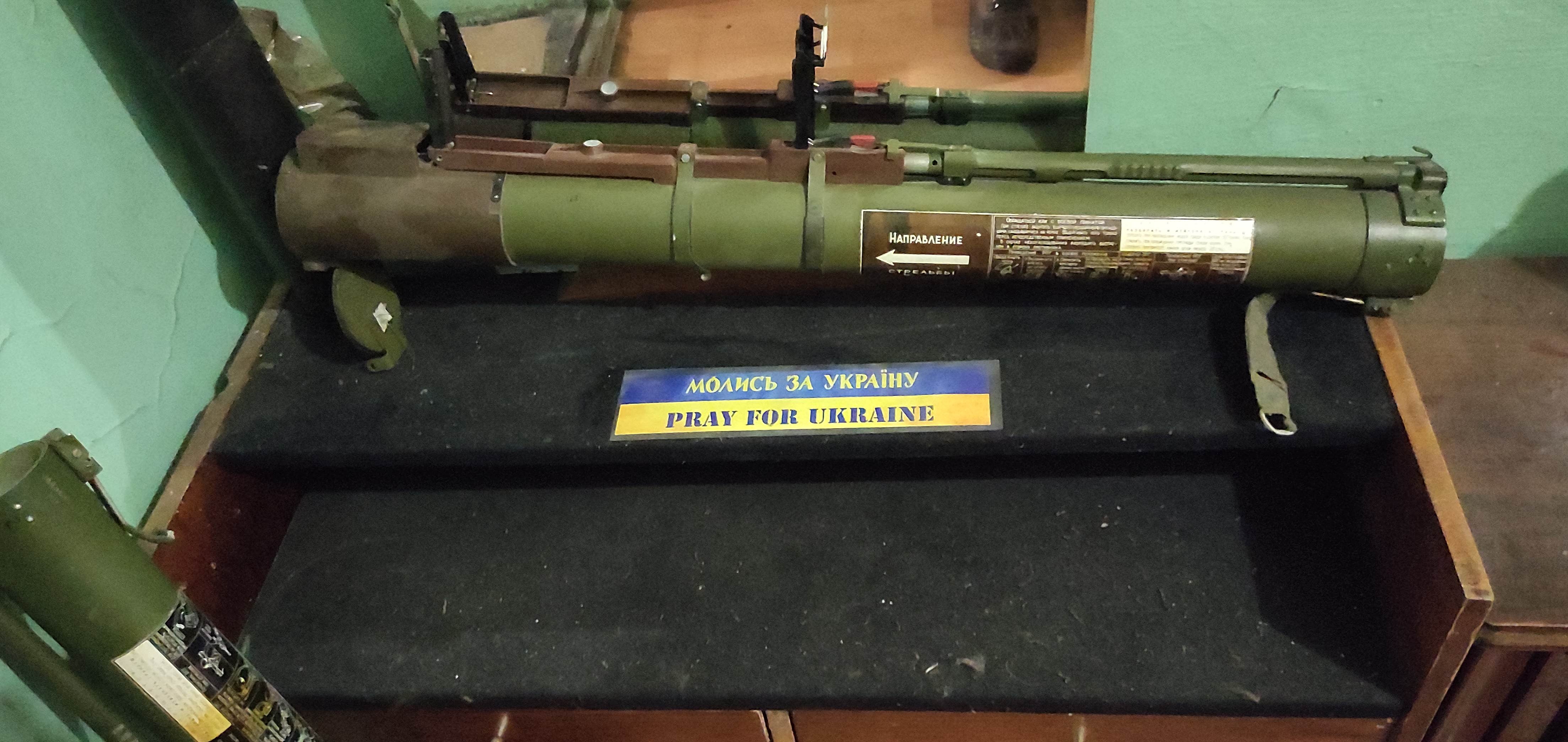

The “mercenaries”, according to Eduard Basurin, have been trained by the British using newly supplied British weaponry. London has sent a consignment of NLAW anti-tank missiles to Ukraine, and has trained around 20,000 Ukrainian troops, and tales of a British “hidden hand” have been a theme in the separatist narrative.

“We are very grateful to the British for sending us the missiles, and we are grateful to all our allies, but [in] the end we also know we’ll have to fight for ourselves. We are not involved in any conspiracies with foreign troops,” says Kotsyubaylo, whose nom de guerre is Da Vinci.

“We don’t know what Vladimir Putin will do. He may start an offensive here in the Donbas, manufacturing some provocation; or he may decide that, with so much international attention, he will not carry out an attack. But the Russians have, as you know, built up a huge force over there, and will they simply go home?”

Pravy Sektor also denies the claims of foreign collusion, insisting any mission it carries out is in liaison with Ukraine’s armed forces, and that its actions are monitored by the government.

Regarded once with wariness and hostility by the country’s military and political hierarchy, it has become more widely accepted after internal changes and successes on the battlefield.

The highly symbolic official recognition of the part the organisation has played in the country’s war came with the awarding of the title of “Hero of Ukraine” to Kotsyubaylo by president Volodymyr Zelensky.

The 26-year-old captain wore combat fatigues at the ceremony, as he was also decorated with the “Order of the Golden Star”, for courage and leadership, while an audience of MPs gave a standing ovation.

Last week, Kotsyubaylo had a meeting with general Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the head of the Ukrainian military, leading to speculation that discussions were taking place about what role the unit might play on the eastern front should hostilities break out.

“General Zaluzhnyi is well liked, respected by the soldiers. They feel that they have his support [which] was not the case with some of his predecessors. That leadership would be very valuable if we have difficult times ahead,” Kotsyubaylo tells me at his base near Avdiivka.

“As for my award, well, there are many, many people who fought bravely; some of them died doing so. What I got was really for everyone. But it is good that the government is recognising the work being done by our unit. We are getting integrated into the armed forces. We are defending our country, as everyone has a right to do.”

We don’t know what Vladimir Putin will do. He may start an offensive here in the Donbas, manufacturing some provocation; or he may decide that, with so much international attention, he will not carry out an attack

The name Da Vinci came from Kotsyubaylo’s days as an art student, and is also a nod to his oft-expressed admiration for the Renaissance polymath.

“I was a student, really interested in academic matters when the Maidan began, and figures like Leonardo da Vinci were my idols. I began to take part in the protests like the others. We were fighting against a government which was trying to suppress our rights; that was my only political motivation. And then, when the Russians occupied a part of our country, we felt it was our duty to fight them,” he says.

Showing me around a museum of the Maidan and the subsequent conflict, which his men and women have put together, he continues: “We are nationalists; I am a nationalist. But we are not [like] some others who are neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and all that stuff. In this unit we have Jews, Muslims, Christians; you’ll not see anyone with a Nazi or fascist tattoo or anything like that. We have volunteers from lots of different countries; we don’t mind where they come from, or their religion.”

Among the items on display at the museum is a short book about Pravy Sektor, written by an Irish volunteer, Patrick, who once served with the unit. There have also been English and Scottish volunteers.

One of the fighters currently in the unit is a Russian, who left Moscow and travelled to Ukraine to fight in the war.

“I had some relations here and I wanted to fight beside them,” he says. “I can’t go back to Russia with the current government there – I’ll face 12 years in prison if I do. I think a lot of people, including Russians, will die if Putin starts a war. I am here to fight if necessary, and I know the Russians put out a lot of propaganda about this unit.”

One focal point of this “propaganda” campaign followed a newspaper interview given by Kotsyubaylo. The unit has raised a wolf, which was brought to them as a cub by Ukrainian soldiers after its mother was shot by hunters. It would be a fitting mascot, they felt, for a unit with three charging wolves in its badge.

Asked by the reporter what the wolf was being fed, Kotsyubaylo replied that the bones in the cage were of “Russian-speaking children”. Soon after he received his award, sections of the Russian media claimed that Ukraine had given one of its highest honours to a right-wing extremist who wanted to feed his wolf with the bones of Russian children.

“It was obviously a joke; you can see it was a joke, anyone could see it was a joke, surely. I was trying to make fun of the type of ridiculous things they say about us, and it got turned into ‘fact’. That is the propaganda war, I suppose; it adds to the way they want to show us, and a way of making people fear and hate each other,” Kotsyubaylo says, throwing his hands in the air in exasperation.

Volunteers in the unit also insist that they are not ultra-right-wingers.

One fighter, with the assumed name Somali, states: “I think both the extreme right and extreme left are pretty stupid. We are here to fight for Ukraine.

“I’ve known Da Vinci for a very long time, and that’s one of the reasons I joined. Another reason is that I think we have more experienced fighters than many regiments in the army. We are more flexible and we are more adaptable. That will be suitable for the type of conflict which may emerge.”

Another fighter, who uses the name Bondik, has had 28 operations following injuries to his arms from a mortar round.

“I could have left after I got wounded. But I’d like to serve Ukraine as long as we have an enemy threatening us. I am here for my country and my comrades, that’s the cause I believe in,” he says.

Pravy Sektor was initially formed as a confederation of radical nationalist groups. Some of these, including one called White Hammer, were expelled. Others, like Patriot of Ukraine, the paramilitary wing of the country’s Social-National Assembly, left the group after it supposedly watered down its militancy.

Some of the more hardline former Pravy Sektor members have found a home in the Azov Battalion, which does little to hide its far-right credentials. At a recent training exercise for citizen volunteers in Kiev, its members wore uniforms with Nazi symbols like the Totenkopf (death’s head), the Sonnenrad (black sun), and the Wolfsangel, or wolf’s trap.

However, it is sometimes difficult to draw clear ideological demarcation lines in the Ukraine conflict.

More than half the members of Azov are Russian-speakers from eastern Ukraine. Its original roots are in a group of ultra supporters of the football team FC Metalist Kharkiv, from a region where 74 per cent of the population are Russian-speaking. Until the Maidan protests, these fans were allied with the ultras of FC Spartak Moscow. Far-right Russian groups have fought alongside the separatists in the conflict against Ukrainian forces.

Most young fighters on both sides of the conflict, whatever their ideological position, talk about how they have lost a part of their life and would like to get back to something approaching normality, if and when the strife ever ends.

Kotsyubaylo met Alina Mykhailova, also 26, a deputy councillor at Kiev City Council and a former activist, while she was delivering donated aid to the front line. They have had a couple of brief holidays abroad together, but, with the possibility of a conflict coming, they are now restricted to brief meetings when he returns to the capital.

Speaking to them at a restaurant in Kiev, I ask them whether they can see themselves ever, in the future, sharing a meal with a separatist couple, also engaged in political and military work but on the other side.

Kotsyubaylo just shakes his head.

Alina says she believes that “this sort of thing will not take place for a long, long time”.

She adds: “Too much has happened; there is too much bitterness. There are painful memories which are just too fresh. And, from what we are seeing now, with the Russians at our border, I don’t think there will be any time to heal.”