The supermassive black hole sitting at the heart of our galaxy is considered to be a slumbering giant. However, an international X-ray spacecraft has discovered that this wasn't always the case. It turns out this supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), has erupted with powerful and dramatic flares over the course of the last 1,000 years.

This surprising discovery made possible by the joint Japanese-European-American XRISM spacecraft (X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission) could change our understanding of how supermassive black holes with masses equivalent to millions or even billions of suns evolve and the role they play in shaping the entire galaxies that swirl around them.

Astronomers are shocked by the finding. "Nothing in my professional training as an X-ray astronomer had prepared me for something like this," team leader Stephen DiKerby of Michigan State University said in a statement. "This is an exciting new capability and a brand-new toolbox for developing these techniques."

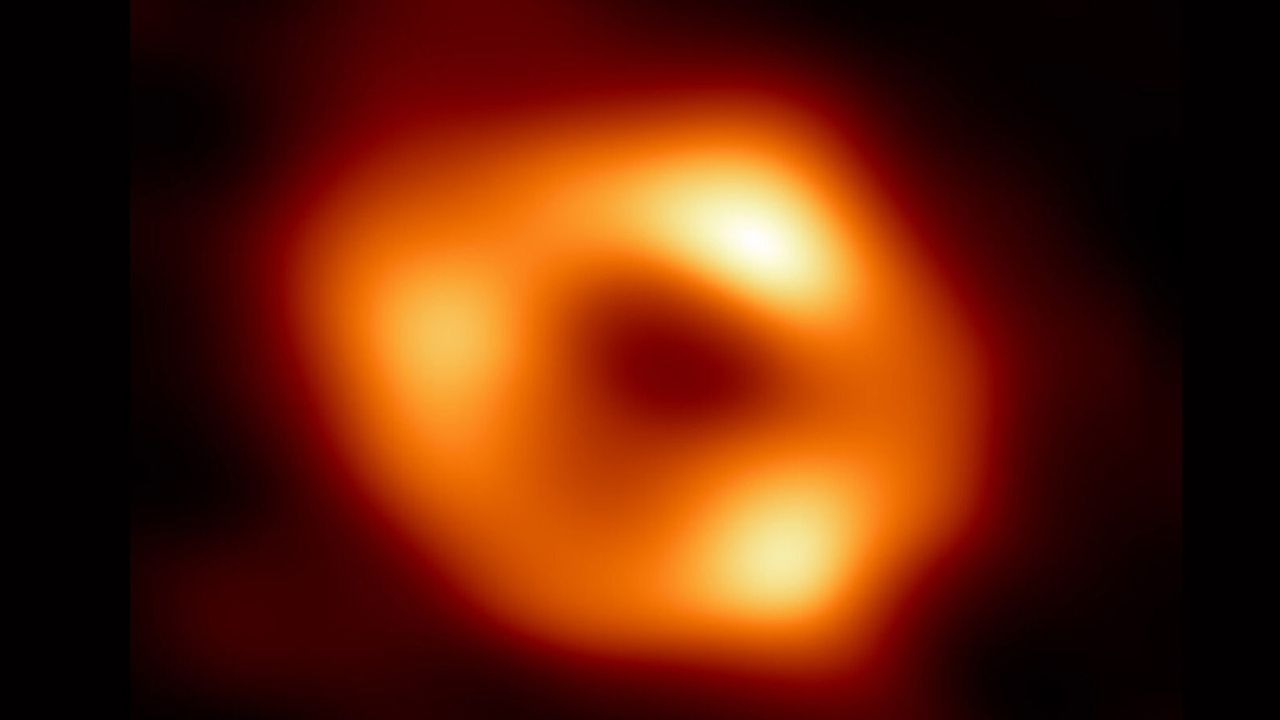

All black holes are completely dark because they are bounded by regions called event horizons, a point at which their gravity becomes so strong that not even light can escape their grip. However, matter around black holes can become superheated by the friction created by the immense gravity of these cosmic titans, causing it to glow brightly and throw out powerful flares. Sgr A*, which has a mass equivalent to 4 million suns, isn't known to have produced such emissions, however.

Or at least it wasn't until now.

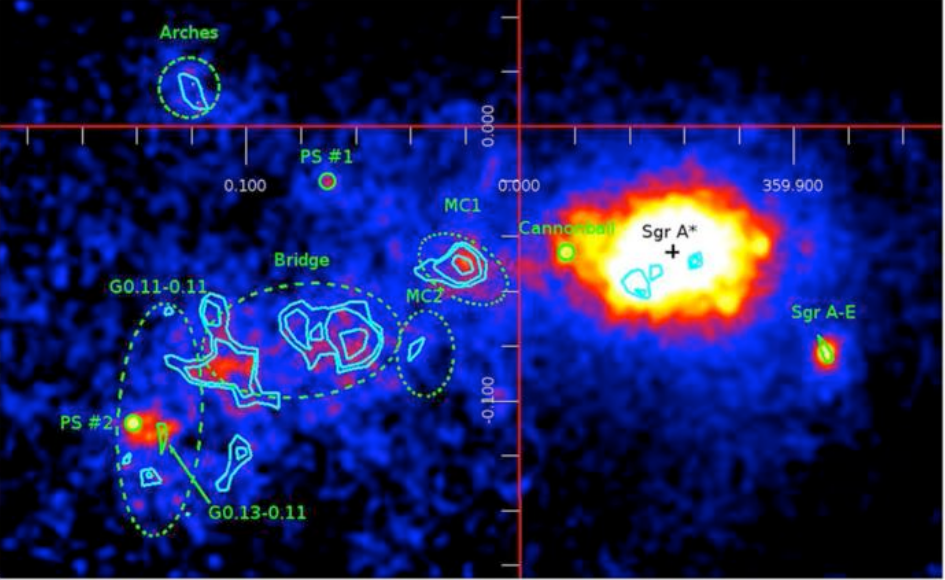

DiKerby and colleagues discovered the black hole's history of turbulence when they pointed XRISM at a giant cloud of gas known as a molecular cloud near the center of our galaxy, examining the X-rays it emits in painstaking detail. This revealed that the molecular cloud was acting as a cosmic mirror, reflecting X-rays previously emitted by Sgr A* flares.

The sensitivity of XRISM, launched in 2023, allowed the team to measure the energies and shapes of X-ray emissions with groundbreaking precision, revealing the movement of the cloud, and also allowing them to test alternative explanations for the cloud's X-ray glow. This ruled out cosmic rays as a cause of this X-ray echo.

The team's findings also reveal that XRISM is perfectly suited to studying the universe in such fine detail that the joint NASA, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and European Space Agency (ESA) mission can uncover the hidden history of the cosmos.

"We're just the lucky scientists who got to solve the problems with handling this data in this brand-new way," DiKerby concluded. "One of my favorite things about being an astronomer is realizing I’m the first human to ever see this part of the sky in this way."

The team's research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.