Astronomers have discovered a rare system of six young planets and a possible seventh that dance around a misbehaving infant star.

Not only could this system provide much-needed insight into how planets form and evolve around an infant star, but its similarity to the solar system could provide astronomers with a snapshot of what our cosmic neighborhood could have looked like around 4 billion years ago.

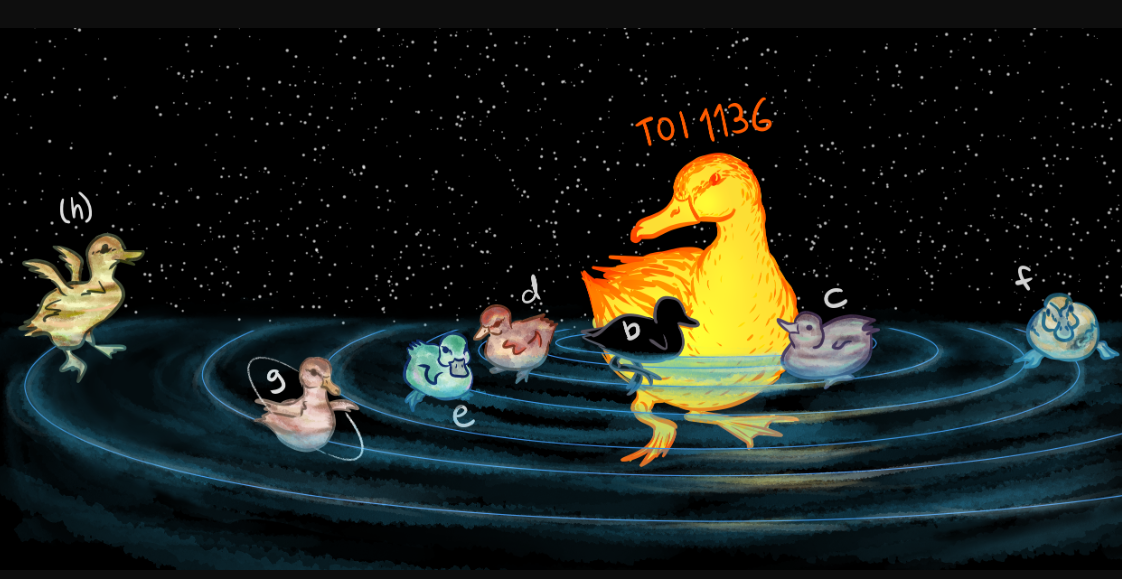

The six, possibly seven, exoplanets orbit a relatively close dwarf star in the Milky Way called TOI-1136; it's located around 270 light-years from Earth. The large number of exoplanets in the system inspired scientists to investigate deeper.

"Because few star systems have as many planets as this one does, it's getting close in size to our own solar system," Tara Fetherolf, team member and a visiting professor of astrophysics at the University of California, said in a statement. "It's both similar enough and different enough that we can learn a lot."

Related: Hubble telescope spots water around tiny hot and steamy exoplanet in 'exciting discovery'

A rare young multi-planet star system with a hyperactive infant star

Scientists initially studied the TOI-1136 planetary system using NASA's exoplanet-hunting Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) in 2019. Fetherolf and colleagues followed up on this initial study with observations from multiple telescopes, revealing the masses of the planets, the shape of their orbits, and even the characteristics of their atmospheres.

The planets in the system, designated names between TOI-1136 b to TOI-1136 g, are classed as "sub-Neptune" planets. The smallest of the six confirmed worlds has a width twice that of Earth, while some of its sibling planets are as large as four times the size of our planet — around the size of the solar system ice giants Uranus and Neptune.

All of the TOI-1136 exoplanets are so close to their parent star that they complete an orbit in less than 88 Earth days. This is significant because 88 days is the orbital period of Mercury, the closest planet to the sun, meaning that all these planets may be closer to their star than that tiny planet is to our star.

"They're weird planets to us because we don't have anything exactly like them in our solar system," Rae Holcomb, team member and a physics Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, said in a separate statement. "But the more we study other planet systems, it seems like they may be the most common type of planet in the galaxy."

What really makes TOI-1136 really stand out is how young this planetary and its central dwarf star are. TOI-1136 is just 700 million years old, which may seem ancient, but compared to the 4.5 billion-year-old solar system and its star, the sun, it makes the system a comparative toddler.

"This gives us a look at planets right after they've formed, and solar system formation is a hot topic," Fetherolf said. "Any time we find a multi-planet system it gives us more information to inform our theories about how systems come to be and how our system got here."

Just like an overactive human toddler, these juvenile stars can be difficult to keep track of because of their hyperactivity. For toddler stars, this overactivity comes in the form of intense magnetism, more prevalent and intense sunspots and heightened solar flares.

The radiation blasted out by infant stars doesn't just make them challenging to observe, it also shapes the planets that orbits them, sculpting their atmospheric characteristics in particular.

"Young stars misbehave all the time. They're very active, just like toddlers. That can make high-precision measurements difficult," Stephen Kane, team leader and a professor of planetary astrophysics at the University of California Riverside, said in the statement. "This will help us not only do a one-to-one comparison of how planets change with time, but also how their atmospheres evolved at different distances from the star, which is perhaps the most key thing."

Could any of the planets of TOI-1136 host life?

Not only are the planets in the TOI-1136 system all relatively the same age, but they are all close together in terms of physical distance, too. This gave researchers a chance to examine something that isn't easy to study in another planetary system.

"Normally, when we're looking for planets, we're looking at the effect the planets have on their star. We watch the star move around and interpret that as the gravitational effects the planets are having on it," Kane said. "Here, we can also see the planets pulling on each other."

This proximity allowed the team to detect a "resonant force" in the system that seems to indicate a seventh world could be gravitationally influencing the confirmed six.

Using the Automated Planet Finder telescope at the Lick Observatory, located on California's Mount Hamilton, and the High-Resolution Echelle Spectrometer at the W.M. Keck Observatory on the inactive volcano Mauna Kea in Hawaii, the team was able to spot the "wobble" of the dwarf star TOI-1136 caused as its planets tug on it.

Combining observations of this "wobble" with computer models and data of the planets crossing the face of their star allowed the researchers to determine the masses of the planets to an unprecedented level of precision.

"It took a lot of trial and error, but we were really happy with our results after developing one of the most complicated planetary system models in exoplanet literature to date," research lead author and UC Irvine Ph.D. candidate in physics Corey Beard said.

The first initial stirrings of life were believed to have emerged on Earth around 600 million years after the formation of the solar system in a period of our planet's history called the Archean. We see the TOI-1136 system exoplanets at a similar point in their history.

The chances of the planets in this system being able to support life seem slim at best, however, due to their proximity to their host star. This means intense radiation from the star is likely stripping the atmosphere of these worlds while boiling away liquid water, a crucial ingredient for life as we know it.

"Are we rare? I'm increasingly convinced our system is highly unusual in the universe," Kane concluded. "Finding systems so unlike our own makes it increasingly clear how our solar system fits into the broader context of formation around other stars."

The team now intends to investigate the TOI-1136 system further, hopefully confirming the seventh planet and also determining the compositions of the planets' atmospheres. This is something that could be achieved with use of the James Webb Space Telescope.

The team's research is published in The Astronomical Journal.