The James Webb Space Telescope began with a five-year-long mission — but thanks to a near-flawless launch, the telescope may be able to keep doing science for far, far longer.

The colossal telescope, which launched early Christmas morning from the Guiana Space Centre near Kourou, French Guiana, is on a mission to change what we know about the cosmos. Right now, has made it to its final orbit spot 1 million miles from Earth. On Monday, the telescope made a critical maneuver to situate itself there.

The James Webb Space Telescope launched with 300 kilograms of fuel onboard its upper stage — enough to park the telescope, essentially, at a point called Lagrangian point 2 (L2) — a position in space where the gravitational pull of two large celestial bodies (the Sun and the Earth) keep a third, smaller object (the Webb) in place. On Monday, the telescope made a critical maneuver to situate itself there, the ESA confirmed.

Everything had to go just right for the spacecraft to reach this point — and according to Mike Menzel, NASA mission systems engineer for the James Webb Space Telescope, it did all that and more — extending the life of the craft by decades.

“When planning our mission we assumed worst-case launch errors as well as worst-case (mid-course correction) timing and execution, which led to a propellant allocation of 146 kilograms for these maneuvers,” Meznel tells Inverse.

But ultimately, the craft only used 32 percent of that.

“This extra propellant can now be used for science mission ops, which at this time could mean over a 20-year propellant life if all remaining activities go nominally.” Meznel says.

The James Webb Space Telescope: Extended mission goals

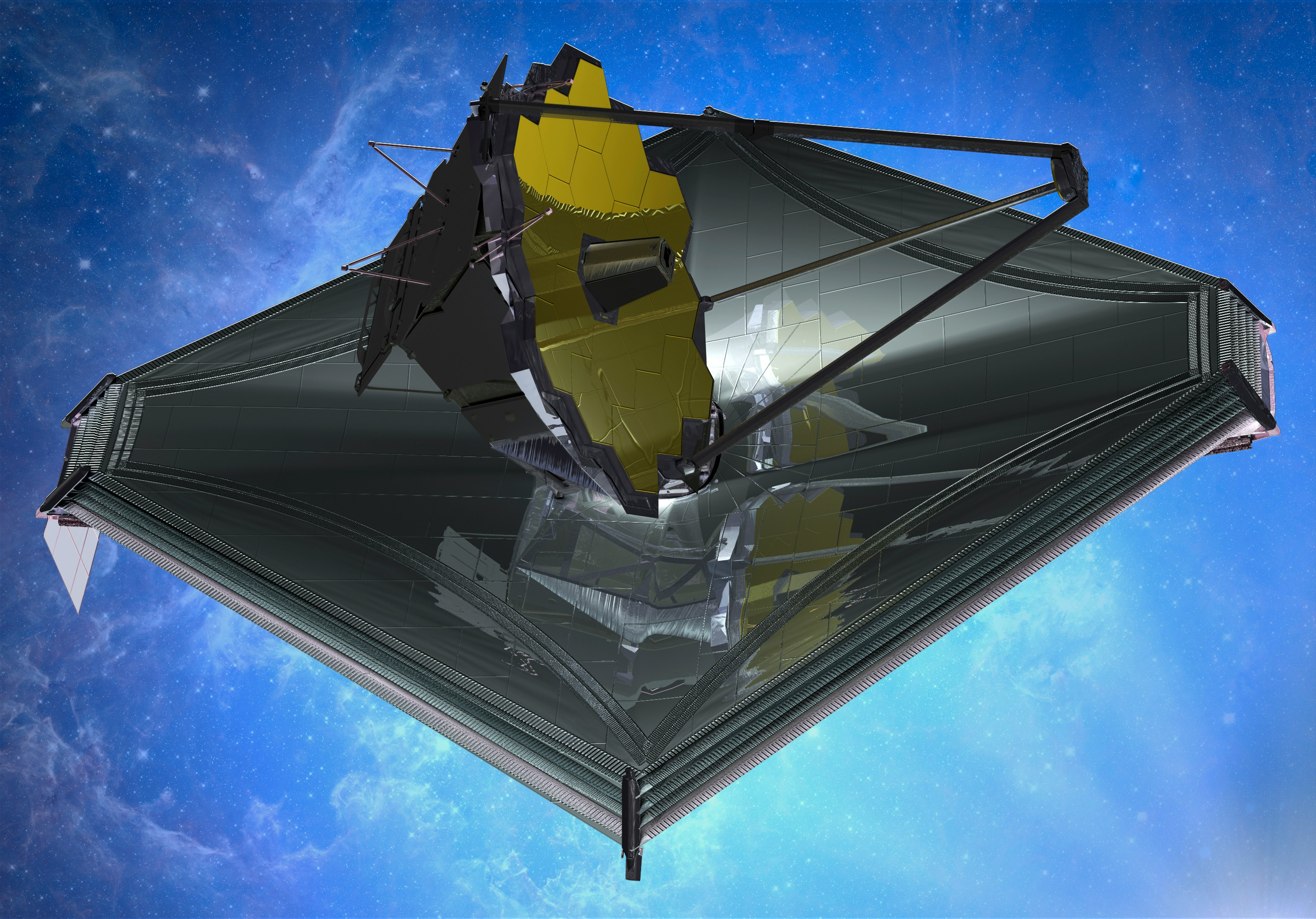

The James Webb Space Telescope is a large infrared telescope designed to peer at a diverse array of objects in space.

The decades-in-the-making telescope will watch distant exoplanets pass in front of their host stars, exhaling telltale atmospheric clues for Webb to pick up on that might help us find life beyond Earth.

It will also peer at the first galaxies that lit up the universe and stare into our home Solar System to give us new information about the least-studied planets and dwarf planets, like Pluto.

The scope will also aid the Event Horizon Telescope in making sense of the giant black hole at the center of our galaxy... and so much more.

It will, in other words, be using its 6.5-meter (21-foot) diameter mirror to help unlock the origins of life and the birth of the universe.

NASA initially gave the telescope a five-year mission, which it still has on paper. Initial projections placed it at having a fuel lifespan of up to 10 years, but the latest projections show that the telescope could potentially last more than two decades.

It’s not uncommon for a NASA spacecraft to far outlast its initial lifespan. The Curiosity rover initially had a two-year mission but is soon to complete its first decade on Mars. The Cassini mission was supposed to have a three-year mission upon arrival at Saturn in 2004 — but instead lasted 13 years examining the system in stunning detail before low fuel led NASA to intentionally crash it into the ringed planet.

Then there are Voyager 1 and 2, which have managed to last 45 years in space thanks to clever 1970s engineering enabling NASA scientists on the ground to shut off high-power instruments when they were no longer needed, extending the missions beyond their basic planetary flybys into charting interstellar space.

The success of the Webb thus far means we will have two decades of observations to look forward to, if not more. While it will take a few months to become fully operational and ready to perform some stunning science, that’s just a fraction of its lifespan now. It’ll join the club of NASA’s biggest workhorse missions in bringing us stunning discoveries for decades.