A 24-hour “"anti-terrorist” operation launched by Azerbaijan to “restore the country’s constitutional order” threatened briefly to escalate into a full-scale war with Armenia over the contested territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. But hostilities have been brought – temporarily at least – to a halt by a ceasefire mediated by the local Russian “peacekeeping” force.

Talks are scheduled for September 21 in Yevlakh in Azerbaijan. On the agenda, according to local sources quoted by the Guardian, will be the disbanding of local militias and the reintegration of the territory into Azerbaijan.

The clash could have easily turned into the third major war over the territory. Though this hasn’t happened for now, the potential for escalation remains as the geopolitical balance of power in the once Russian-dominated South Caucasus continues to remain in flux.

The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh goes back decades to before the break-up of the Soviet Union. After a period of bloody inter-ethnic clashes between Azeris and Armenians in then Soviet Azerbaijan starting in 1988, a full-scale war between newly independent Armenia and Azerbaijan erupted in 1992.

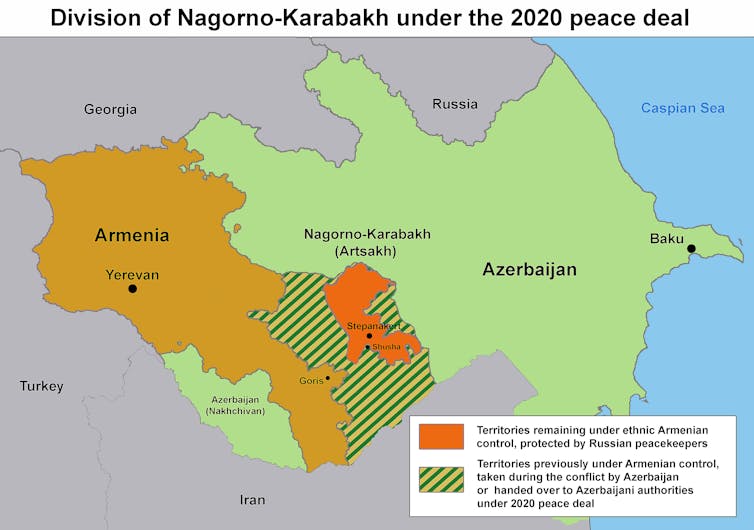

By the time a Russian-brokered ceasefire stopped the violence in May 1994, more than 100,000 people were dead or wounded and more than one million displaced. The war ended with an Armenian victory that established control, not only of Nagorno-Karabakh, but also of other territory within the internationally recognised borders of Azerbaijan. This included the Lachin corridor, a strip of land connecting Armenia with Nagorno-Karabakh.

Amid futile, low-level tensions and violence persisted for the next two decades, pierced by intense flare-ups 2008 and 2014. In April 2016, another clash along the volatile ceasefire line escalated. For the first time since 1994, Azerbaijan recaptured some of its territory before another Russian-brokered ceasefire brought an end to the fighting.

More than four years later, between September and November 2020, Azerbaijan launched another offensive which ended with significant territorial gains, including of Nagorno-Karabakh’s second largest city of Shusha.

This second war again ended with a ceasefire, mediated by Russia and establishing Russian and Turkish “peacekeepers” in the region.

Build-up and escalation

Despite the ceasefire, very little progress was made towards a permanent settlement of the conflict. EU efforts to mediate between the sides looked promising in mid-2022, but ultimately faltered.

With no progress in talks being made, Azerbaijan started to increase pressure on Nagorno-Karabakh in December 2022, blocking access to the region via the Lachin corridor. Even the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) – the only humanitarian organisation able to cross the Lachin corridor – was only able to deliver 77 trucks of medical and food assistance between December 2022 and August 2023.

As the authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh refused aid delivered directly from Azerbaijan via the Aghdam road, an unprecedented humanitarian crisis developed in the Armenian enclave.

The hope that this situation had been resolved after almost eight weeks of a complete blockade with a simultaneous aid delivery facilitated by the ICRC via both routes on September 18 2023, was quickly shattered by the launch of Azerbaijan’s new offensive.

The Russia factor

The latest escalation of fighting is also indicative of Russia’s changing position in the region. For decades Moscow had been the undisputed regional powerbroker. Crucially, Moscow also backed Armenia and guaranteed the territorial status quo. This image was weakened, however, by the 44-day war in 2020 when Russia refused to heed Armenian calls for help.

The ceasefire agreement brokered by the Kremlin in November 2020 could still be seen as a strengthening of Moscow’s position in the South Caucasus. It established Russian “peacekeepers” on the ground where there had been no Russian military presence before. They may have failed to carry out the key task they were charged with – to ensure the Lachin corridor between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh remained open – but remained enough of a force to broker the ceasefire that halted the Azeri offensive.

The Azeri success signals more broadly a possible shift in the geopolitical power balance in the South Caucasus. Azerbaijan has leveraged Turkish support and its increasingly strong ties with Israel to flex its muscles in the disputed region.

At the same time, relations with the EU have also warmed since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Brussels considers oil and gas-rich Azerbaijan as a potential partner in ending its energy dependence on Russia.

But this is not necessarily the end of the story. Russia may be distracted by its aggression against Ukraine, but its current manoeuvring is not purely out of weakness. Azerbaijan’s renewed escalation is likely to increase Armenia’s internal political instability. There’s a distinct possibility this might lead to the overthrow of the country’s current government.

This administration has been openly critical of the Kremlin’s handling of the Nagorno-Karabkah situation for some time – and recently held joint military drills with the US.

So the desire for a more pro-Russian and anti-western government in Yerevan might well explain Russia’s reluctance to act more decisively in defence of the status quo.

But there’s another dimension to the already complex situation that may favour Russia: the role of Iran. Russian-Iranian ties have grown significantly over the course of the war in Ukraine. Meanwhile, tensions between Iran and its neighbour Azerbaijan have escalated, partly over Azerbaijan’s growing closeness to Israel.

Russia’s defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, rushed to Tehran on September 19 to meet the chief of Iran’s general staff, Mohammad Bagheri. They discussed the escalating violence in Nagorno-Karabakh – another sign of the general shift in the regional power balance.

Russia may appear to be on the back foot in the South Caucasus and its distraction in Ukraine may sound like a logical narrative to explain that. But it is far from clear whether Russia has, indeed, been distracted or surprised. Perhaps it has instead learned how to play a weaker hand to its continuing advantage.

Stefan Wolff is a past recipient of grant funding from the Natural Environment Research Council of the UK, the United States Institute of Peace, the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK, the British Academy, the NATO Science for Peace Programme, the EU Framework Programmes 6 and 7 and Horizon 2020, as well as the EU's Jean Monnet Programme. He is a Senior Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Centre in London and Co-Coordinator of the OSCE Network of Think Tanks and Academic Institutions.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.