Had things been a little different, Nadhim Zahawi, rather than Rishi Sunak, might have become Britain’s first non-white prime minister. Tory politics were unusually chaotic and febrile last summer, after all, and it didn’t seem such an outlandish prospect. However, a story in The Independent on 9 July that revealed he was being investigated by the tax authorities threw sufficient doubt on Zahawi’s candidacy that he failed to get further than the first round.

He did still win the support of 25 Conservative MPs, beating Jeremy Hunt into last place on 18, but it was nowhere near enough for him to carry on. Perhaps, all things considered, it is just as well that he didn’t make it to No 10.

He was certainly near the top of the greasy pole. Last July, going into the leadership election, Zahawi had extracted the post of chancellor of the Exchequer from the beleaguered Boris Johnson, in return for not resigning along with Sunak and dozens of other ministers as the Johnson government disintegrated. He’d declared his loyalty to Johnson, but the very next day he called on Johnson to resign – while he himself carried on as chancellor.

Zahawi recruited the well-known political strategist Lynton Crosby to help him with his leadership bid. He had a good backstory, and was well liked by the grassroots. Britain’s highly successful vaccine rollout was his responsibility – he had been handed the task by Johnson, who had had enough of the “f***ing hopeless” Matt Hancock. As Zahawi remarked at the time: “If a young boy who came here aged 11 without a word of English can serve at the highest levels of Her Majesty’s Government and run to be the next prime minister, anything is possible.”

Indeed so. Born in Baghdad to a Kurdish family in 1967, Zahawi arrived in the UK after his family fled the rule of Saddam Hussein. There’d been a tip-off that Saddam’s men were due to pay them a visit. The Zahawis originated from Khanaqin, an oil-rich city in the east, close to the border with Iran, and their prosperity, influence and background did not commend them to the Ba’athist regime.

This particular refugee family came over on Swissair rather than in a dinghy, and we now know how Zahawi in due course was to make good use of his father Hareth’s family money and his business. Grandad Nadhim al-Zahawi even had a brief spell as governor of the Central Bank of Iraq. They were old establishment, and were probably lucky to have been left for as long as they were.

Little Zahawi was sent to school at Holland Park Comprehensive, a state school of progressive outlook in a posh area, before attending a fee-paying establishment in Wimbledon and going on to University College London and a degree in chemical engineering. Not Eton and Oxford, but not a bad start in life, either.

Then came the money-making. All fine, but as we know from bitter experience, money and politics don’t mix. After a spell as marketing manager with Smith & Brooks Ltd, a clothing manufacturer, in 2000 Zahawi co-founded polling company YouGov with Stephan Shakespeare, a Conservative activist and associate of Jeffrey Archer. Zahawi was chief executive for a time, the firm was very successful, and Zahawi made a lot of money out of it – some £27m, it has now been reported.

How the money was made, the role of his father and of a Gibraltar-based offshore trust, and the tax status of the capital gain on the investment are complex matters, and the subject of much comment. But, along with other enterprises, it added to the Nadhim Zahawi family fortune, which some estimates put at £100m or more.

Great wealth brings big questions, though, and even now, the exact details of the wider role played by Balshore Investments, along with Zahawi’s profitable property portfolio, isn’t fully detailed in the public domain. Recently Zahawi stated: “HMRC agreed with my accountants that I have never set up an offshore structure, including Balshore Investments, and that I am not the beneficiary of Balshore Investments.”

Questions about the source of around £30m of unsecured loans made to his wife’s UK property company remain unresolved. Zahawi married Lana Saib in 2004, and not much is known about her other than the fact that she’s involved in business and is also an equestrian.

This, then, is the man Johnson made chancellor of the Exchequer last summer, and thus placed in ultimate control of HMRC and British tax policy. If nothing else, there were surely some potential conflicts of interest. These may have been declared, confidentially, to the permanent secretary at the Treasury or to the cabinet secretary, as is routine practice, but if so, the public were not informed.

Nor do we know for sure what the three prime ministers Zahawi served – Johnson, Liz Truss, and Sunak – knew of these matters, or of the HMRC investigation and penalty. In any case, he was an odd pick for HM Treasury, even as a caretaker.

Politically, Zahawi’s rise was as conventional as his fall was, well, complicated. He served a few terms as a councillor in Tory Wandsworth, and fought an unwinnable seat in 1997 before landing the safe constituency of Stratford-upon-Avon in 2010 (which John Profumo had once represented before being forced to quit in disgrace). Funnily enough, in Zahawi’s maiden speech, he made a plea for an easement in capital gains tax, and with no specific declarations of interest:

“I am someone with first-hand experience of a start-up. We must be careful what we do on capital gains tax ... it is important to remember the job creators, those who back them, and those who join them and work for them. It would be counterproductive to penalise people who invest in start-ups – in itself a high-risk thing – by increasing capital gains tax on their investment. It would also be wrong to penalise employees who join a risky start-up from possibly a safer occupation, and, of course, to penalise entrepreneurs themselves.”

Under David Cameron and Theresa May, he enjoyed steady if unspectacular promotions. He was embarrassed by a sexist Tory fundraising party (he left early), but the only serious stumble was the discovery that he’d claimed £5,822.27 in parliamentary expenses to cover electricity and heating oil for stables on his estate, a second home, in Warwickshire. Even before the energy crisis, the idea of using taxpayers’ money to keep his pet nags nice and toasty was pretty outrageous. He declared himself “mortified” and paid the money back.

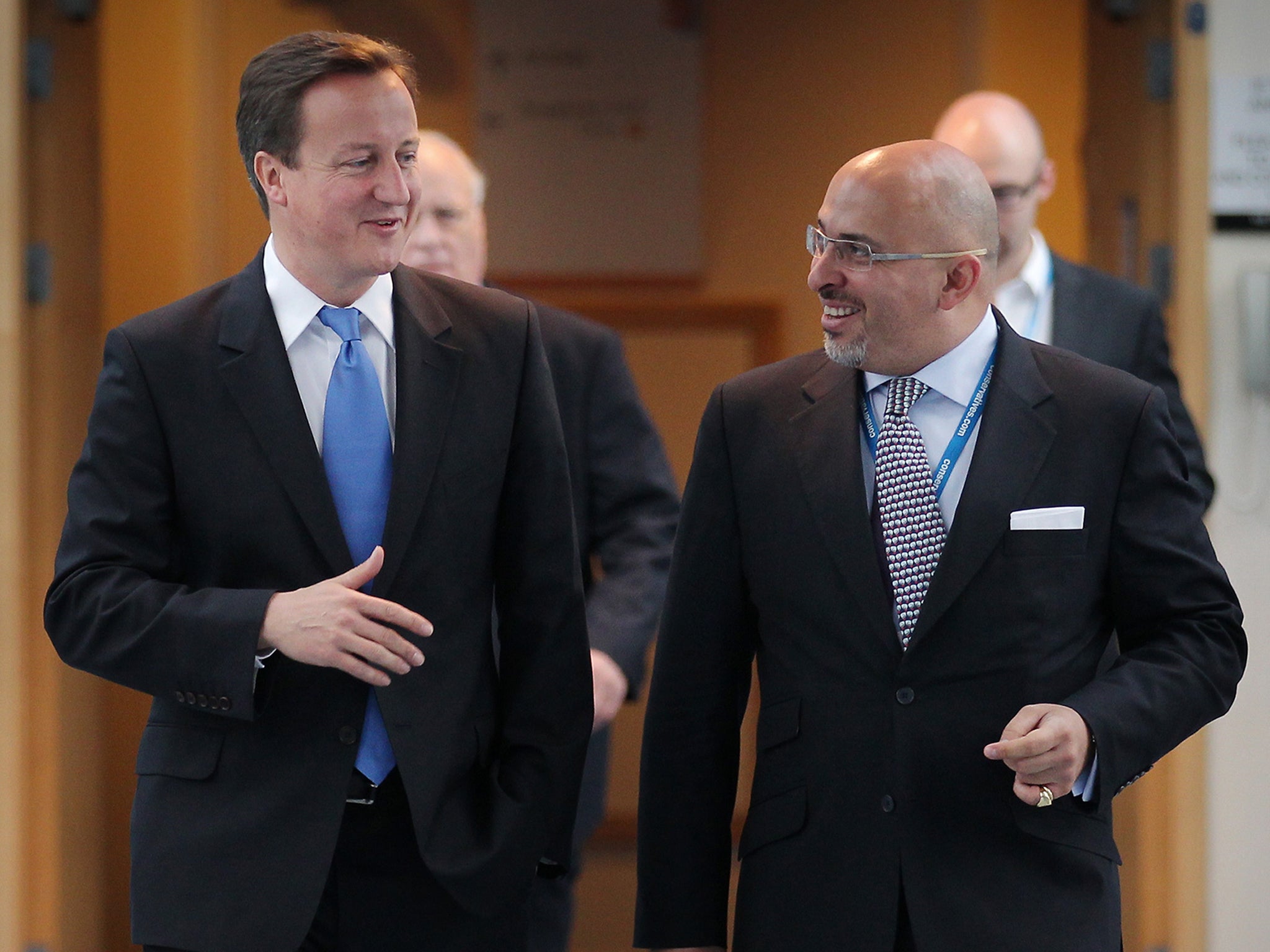

Zahawi is generally unkeen on too much transparency, it’s fair to say – a theme that runs throughout his career. While he served on the foreign affairs select committee, for example, he failed to declare his membership of Le Cercle, a private foreign policy forum; his links with the oil industry have also been criticised, particularly in relation to his role as vice-chair of an all-party group on Kurdistan. He was also caught up in the Greensill lobbying affair, after which text messages between Zahawi, Cameron, and the businessman Sanjeev Gupta were found to have disappeared.

All was pretty much forgiven, however, when Johnson made the inspired decision to appoint Zahawi “vaccines minister” during the Covid pandemic, wrenching the role out of the control of Matt Hancock. It was Zahawi’s big break, and he was entirely justified in his resignation letter for taking credit for his part in one of Britain’s few recent success stories: “This saved huge numbers of lives. It is also what has allowed us to move beyond Covid and get our economy and society moving again ... Policy making and delivery are normally treated as two separate processes. In the vaccine rollout, they were combined, and I think that accounts for why it worked so well. If we could apply this model to other parts of government, I believe it could have transformative results.”

It was to prove his finest hour. Zahawi was almost certainly wounded by a political enemy, though the tragic flaws in his personality and the complications money brings would have compromised him eventually anyway. As someone of great drive and intelligence, and still only 55, Zahawi could have done much more for his country and been remembered for more worthy things than tax and quibbling over the word “careless”. But “careless” in all sorts of senses will now serve as his epitaph. Or, to borrow the words of the most famous constituent of Stratford-upon-Avon, in his play Richard II:

“Thou liest in reputation sick: and thou, too careless patient as thou art, commit’st thy anointed to the cure of those physicians that first wounded thee.”