A skeleton visible within a burial at the entrance of the palace of Hernán Cortés —the Spanish conquistador who caused the fall of the Aztec Empire — is not the remains of a Spanish monk as was long thought. Instead, a new analysis reveals that the bones belonged to a middle-aged Indigenous woman.

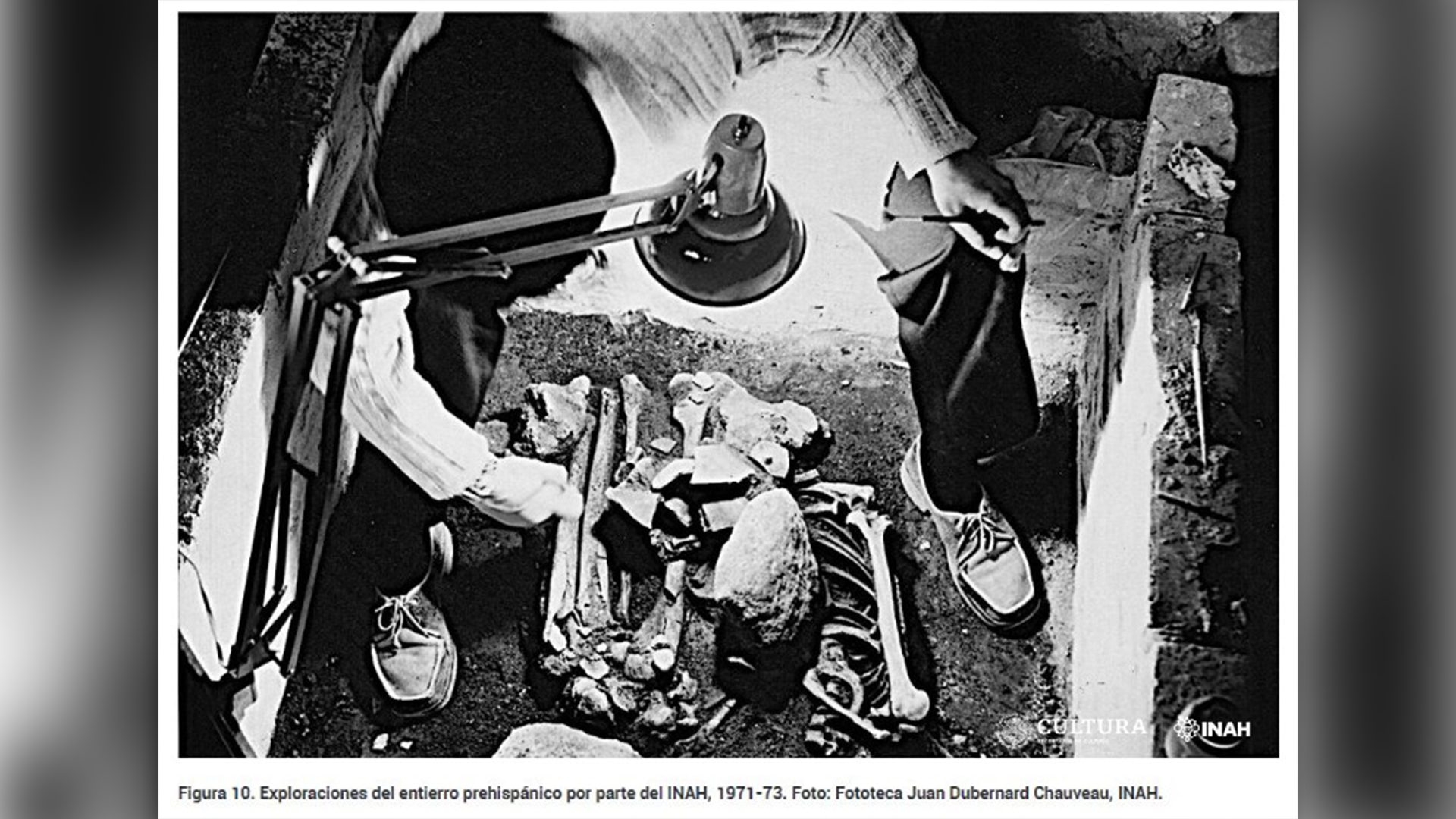

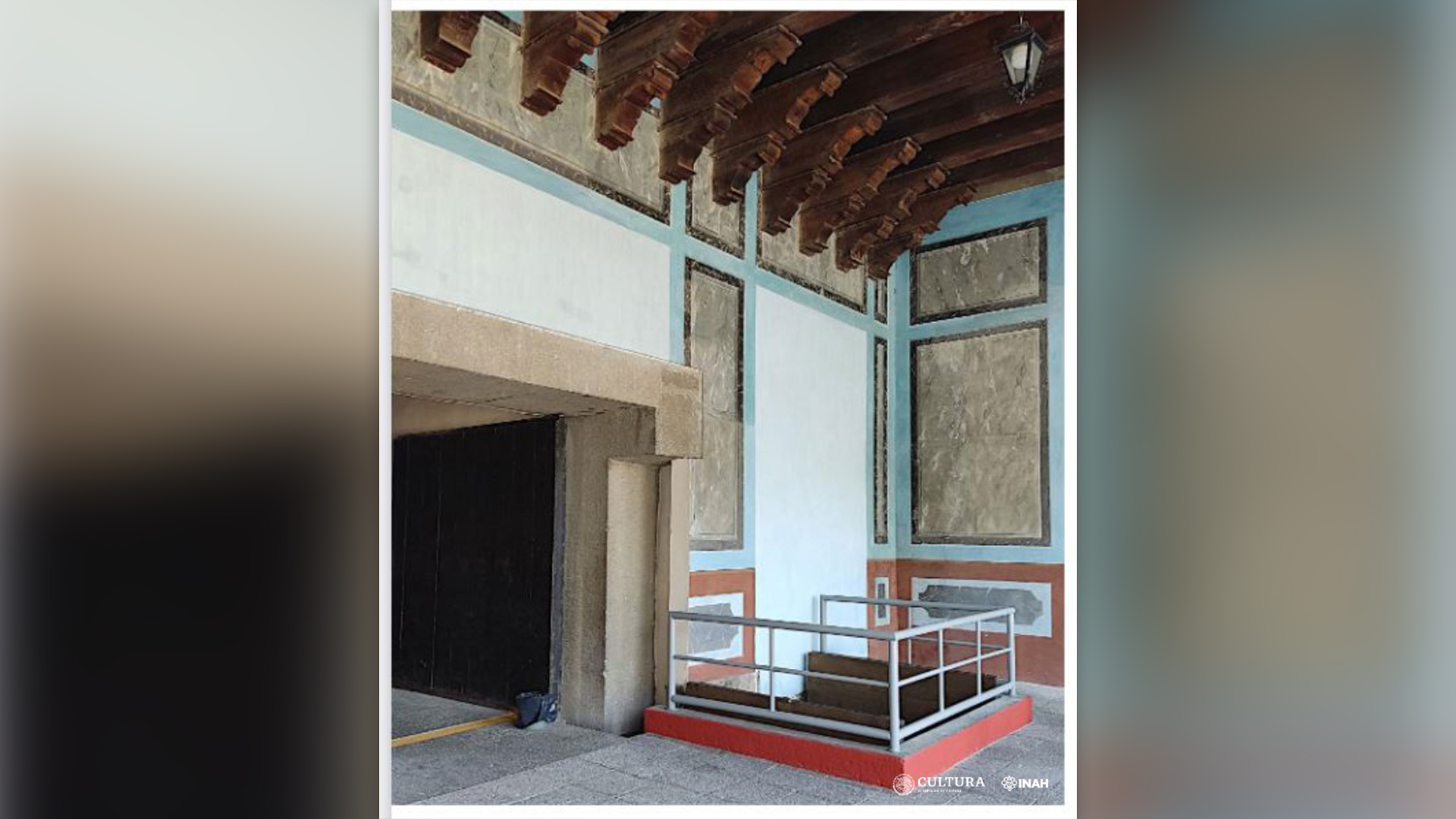

When a powerful magnitude 7.1 earthquake rattled the Mexican states of Puebla and Morelos as well as Mexico City in 2017, buildings collapsed and thousands of people were injured. The Palace of Cortés, which was built by 1535 and now serves as a museum, was severely damaged, requiring extensive repair work that was completed in early 2023. During this work, researchers took stock of all objects within the museum, including an open burial exhibited at the entrance to the palace.

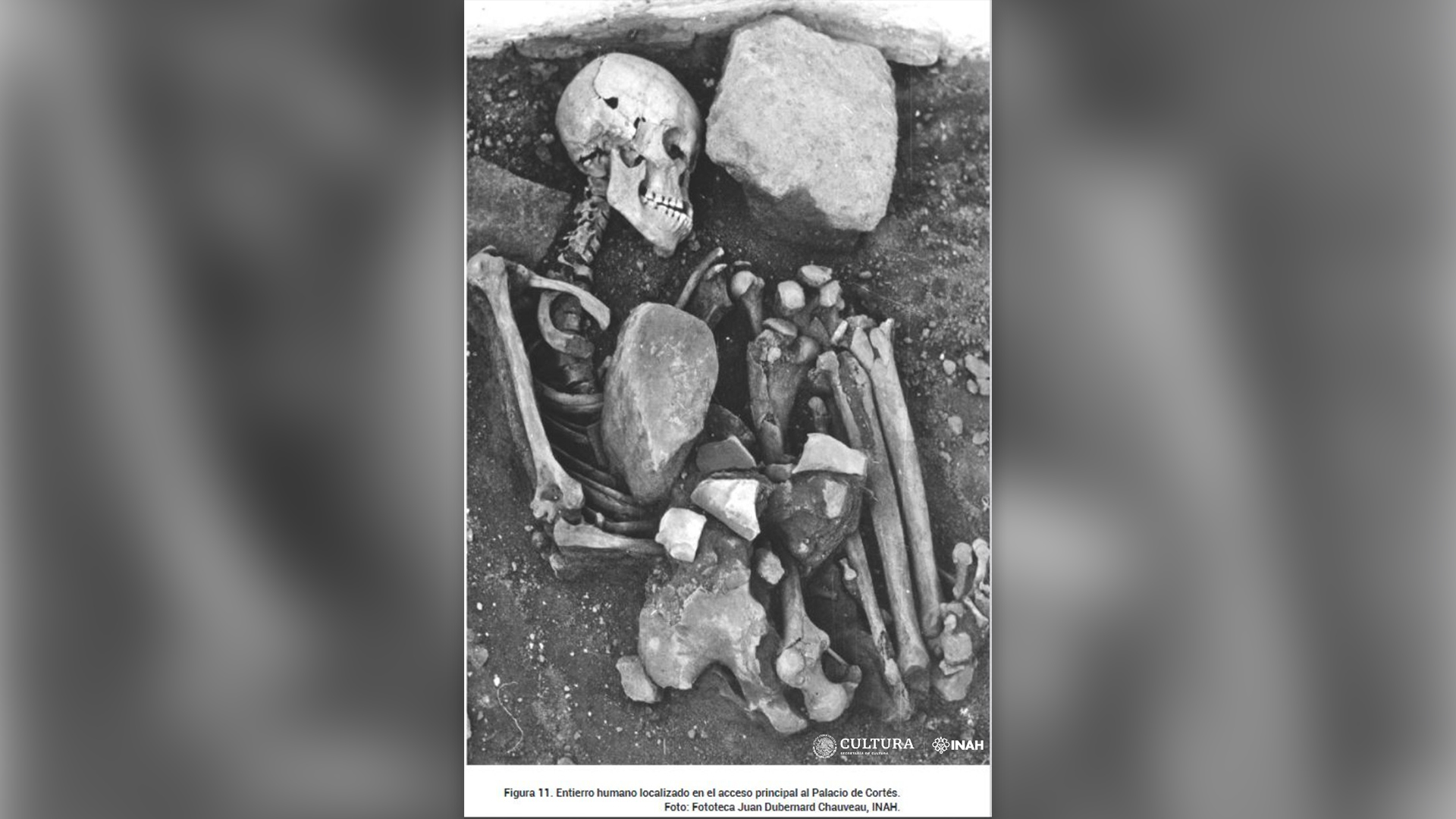

Originally excavated in 1971, the burial was left in place, and was eventually walled off and accompanied by a label noting that the person was likely the Spanish monk Juan Leyva. To arrive at this identification, a team of historians had found a 16th-century Franciscan codex that told the story of how Leyva slept with his head in a niche in the wall and how he was eventually buried next to the gate of the old house. After archaeologists noticed some issues with the neck vertebrae in the burial, the pieces fell into place: The skeleton with a twisted neck at the palace's entrance could have been Leyva.

Despite these clues, other aspects of the burial did not mesh with what would be expected for a Spanish monk, including the fetal-like burial position.

In a Jan. 18 statement, Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) announced a new analysis of the burial, with a wildly different identification: the supposed Spanish monk burial was actually the remains of an Indigenous woman.

Related: Ancient burial of fierce female hunter (and her weapons) discovered in Peru

INAH anthropologists Pablo Neptalí Monterroso Rivas and Isabel Bertha Garza Gómez undertook a thorough examination of the remaining bones in the burial and detailed their findings in a published report.

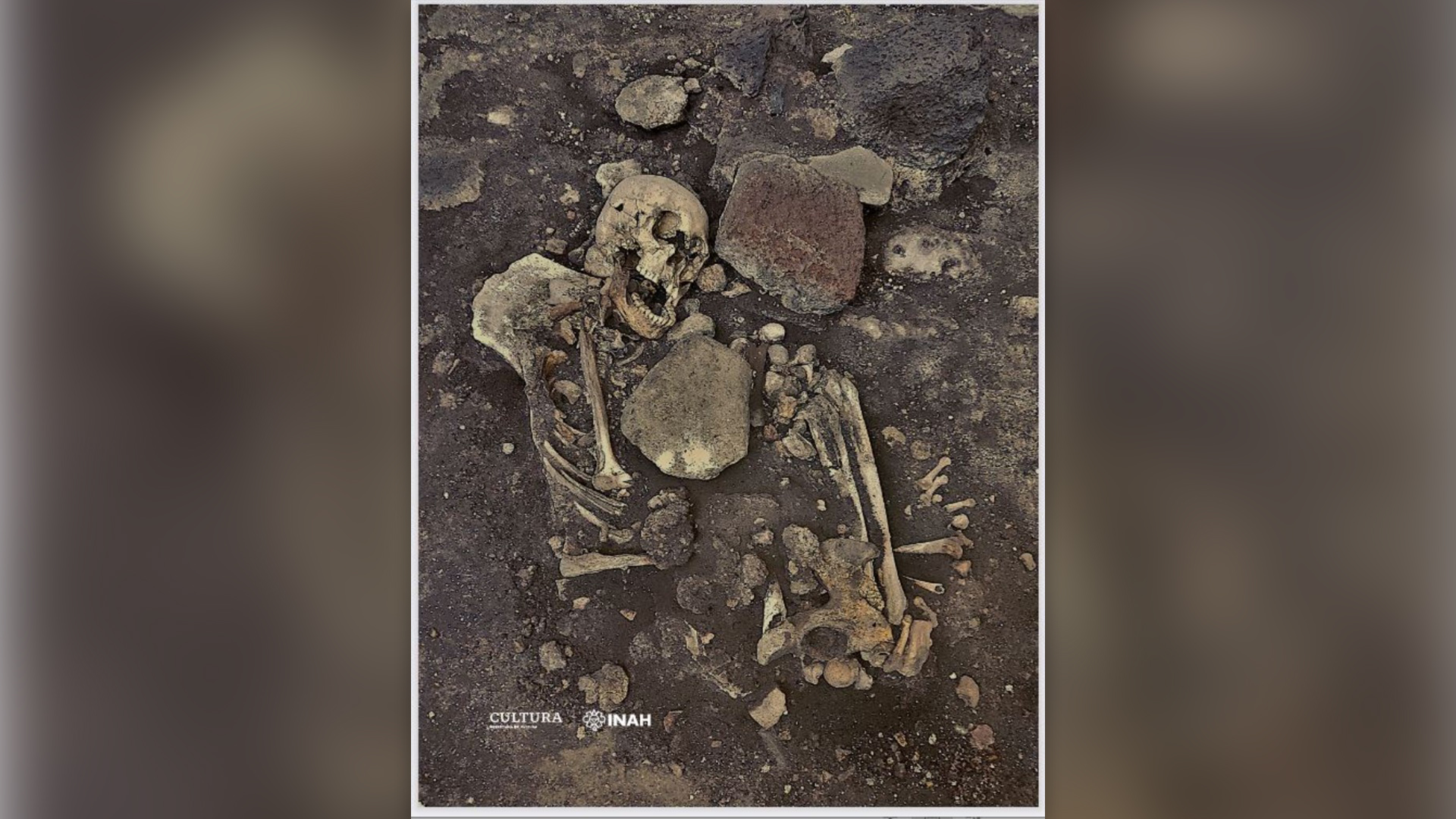

Both the skull and the pelvis suggest the person was female, who was about 30 to 40 years old when she died, Monterroso Rivas and Garza Gómez noted in the report. They did not see any clear indications of the "distorted" neck vertebrae that the 1971 researchers noted, but they did see some flattening of the back of the woman's head, likely from the practice of cranial modification. A fetal-like burial position along with cranial flattening suggests an Indigenous origin for the skeleton, they wrote in Spanish. But why was she buried in the Palace of Cortés?

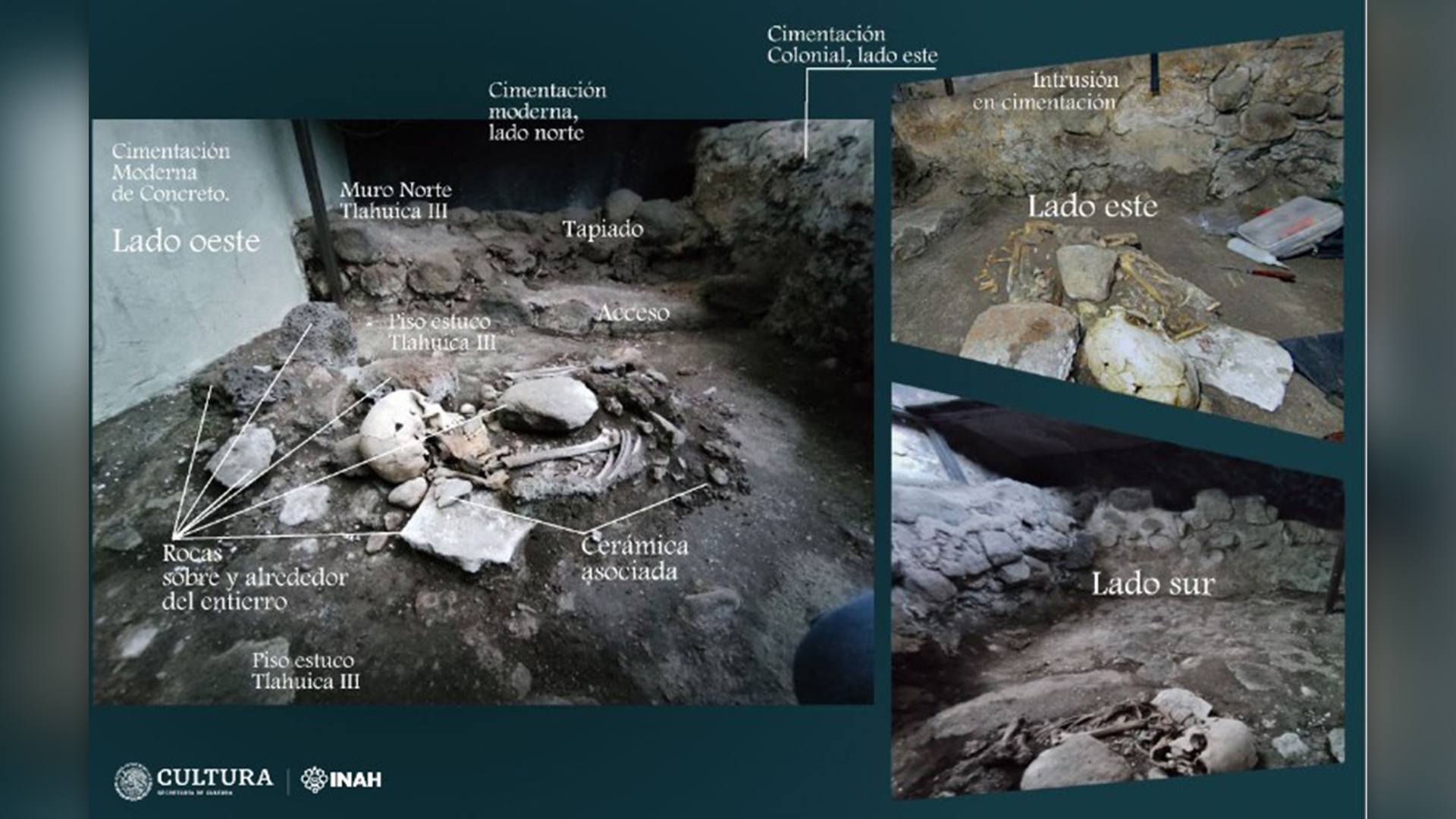

Beginning around 1150, centuries before Cortés set foot in central Mexico, the region was occupied by the Tlahuica, an Aztec people. They built a city called Cuauhnáhuac (modern-day Cuernavaca), which was wealthy, full of buildings and densely populated at the time of Cortés' incursion. Upon destroying the city in 1521, the Spanish burned the "tlatocayancalli" — the Aztec tax collection house — and built a palace for Cortés on the ruins.

Given the archaeological evidence for various floors that were put in over time, the anthropologists suggested that the Tlahuica woman was buried very close to the time that Cuauhnáhuac fell to Spanish invasion, between 1500 and 1521. In an email to Live Science, Monterroso Rivas suggested that, rather than a traditional cemetery-type burial, "it would be more pertinent to think of a series of ritual events, perhaps of sacrifice, with the Tlahuica woman being the last to take place."

Even though a new identification of a historical burial has been made, there are still open questions. The anthropologists reexamining the burial also identified a handful of bones from other individuals, including an infant and a child. Monterroso Rivas does not know if the two children were kin, but he suggested that a DNA study could clarify their relationship. And after half a century of exposure and years of humidity issues following earthquake damage to the palace, the Tlahuica woman's skeleton is seriously damaged — the team hopes that the skeleton can be preserved and studied more in the future.

"It is worth reiterating the importance of the burial and its emblematic association with the palace," they wrote in their report, since "the archaeological window" was created to show the burial, which greets guests who visit the museum.