In a new series, we look at books that have become cultural touchstones.

I took a shower once a week at most. I stopped tweezing, stopped waxing, stopped brushing my hair. No moisturising or exfoliating. No shaving. I left the apartment infrequently. I had all my bills on automatic payment plans. I’d already paid a year of property taxes on my apartment and on my dead parents’ old house upstate.

Zoned out on Xanax, Ottessa Moshfegh’s unnamed anti-hero is living the “goblin-mode” dream. It’s a dream that might have been considered out-of-touch if My Year of Rest and Relaxation were published when it’s set – at the optimistic pre-September 11 dawn of the New York new millennium. But it’s a dream that’s all too relatable in these post-pandemic times, where lockdowns, a waning will to work, and gnawing existential angst have become familiar parts of the collective consciousness.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation centres on a 27-year-old female protagonist – white, thin and cashed up – who embarks on a mission to sleep away her ennui for an entire year. Aided by a complex cocktail of every relaxant known to psychiatry (and even a fictional one, “Infermiterol”, that isn’t), the narrator sees her hibernation as a chance for rebirth. It’s a way to break free from the pain of an unloved childhood and a superficial present punctuated by avant-garde art snobs and an inattentive on-off boyfriend.

A critical and fan hit

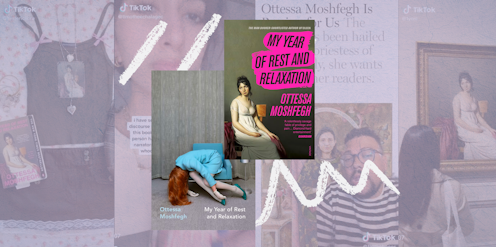

Four years after its release, Moshfegh’s second novel has become a publishing and cultural phenomenon, complete with TikTok trends and Margot Robbie-acquired film rights. Resonating across generations, it’s been as much a hit with literary luminaries as with a multitude of millennial and Gen Z fans, who have analysed its themes and fetishised its supposed “sad-girl” aesthetic on social media.

With a job-ending public defecation, a bleak parking-lot blow job, and a subversive scene celebrating the primal pleasure of two female friends watching porn following a funeral, our protagonist’s pastimes sound sordid but have been lauded as refreshingly transgressive and relatable.

Depressing, sure – but in the same way that a blues tune can soothe a sore soul, Moshfegh’s edgy eloquence and turn-of-the-millennium nostalgia (remember AOL chat, the dying days of VCR, the Yellow Pages and vogueing?) have struck a chord with readers.

The protagonist may be “unlikeable” to some, but she and Moshfegh are also cuttingly funny. Take for example, lines like: “If it weren’t for the specter of death hanging over everything, I would have felt like I was in a John Hughes movie.” Or, from the narrator’s psychiatrist Dr Tuttle: “Education is directly proportional to anxiety, as you’ve probably learned, having gone to Columbia.”

Read more: What is BookTok, and how is it influencing what Australian teenagers read?

Smug and problematic?

My Year of Rest and Relaxation is not for everyone. And its popularity in the sad-girl sphere does raise some questions.

Does the narrative glamourise addiction and mental ill-health, presenting a solution dependent on endless cash, cultural capital and the smug satisfaction of being young and hot? Is it really a valuable contribution to the canon at a time when so many are struggling to access mental health services and affordable, safe housing?

It’s certainly true that media depictions and social media trends featuring or glorifying destructive behaviours can be problematic and have real-life consequences. While TikTok has been praised for normalising fourth-wave feminist issues and female agency, studies have also indicated that media and popular culture portrayals of crime and suicide can (and do) inspire copycat behaviour.

However, critics would do well to remember that depicting destructive behaviours and toxic cultures does not necessarily condone them, particularly in the realm of fiction.

Novelists have long fought against the idea that that their characters and plotlines need be literal in pointing the way to solutions to society’s ills. “I don’t like literature that moralises anything,” Moshfegh said in a recent interview. “I mean, I think it’s the most boring way to direct a reader’s experience.”

Read more: Ghoulishness, depravity and stupidity: welcome to the world of Ottessa Moshfegh's Lapvona

Moral rights of artists

While most would agree that insisting authors only write about well-adjusted people in a perfect world is not the way forward, what of the moral right of artists whose work may have been taken in unwanted directions on social media?

The music of Fiona Apple, another (reportedly reluctant) heroine of the “sad girl” movement, is a case in point. Most of her catalogue was recently – apparently temporarily – removed from TikTok. And while Apple and her label Sony have been tight-lipped around the reasons, some have applauded it as a sign of Apple’s integrity and unwillingness to be misappropriated.

Such a stance might make sense for musicians who established audiences pre-social media, but it’s hard to imagine an author eschewing the world’s fastest-growing platform – even if they didn’t like what fans were saying (and it were possible from a copyright perspective). With 71.8 billion views and counting, the hashtag #BookTok has been credited with making reading cool with young people again, and extending the shelf-life of older books by opening them to new audiences.

But back to Moshfegh and My Year of Rest and Relaxation. Is the book a satire, or isn’t it? Is it feminist, post-feminist or does it put the sisterhood back 20 years? While fans and critics can continue to debate such questions, Moshfegh must be laughing all the way up the bestseller lists.

Charlotte Chalken does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.