In this new series, our writers introduce us to a favourite painting.

For almost as long as I can remember I have loved the pictures of Paul Klee (1879-1940). When I was growing up my parents owned a strange little lithograph by him called Phantom Perspective. It shows a wafer-thin man lying asleep in a dormitory of inflowing straight lines.

Like one of the curious fish in Klee’s child-like visual aquaria, I was hooked.

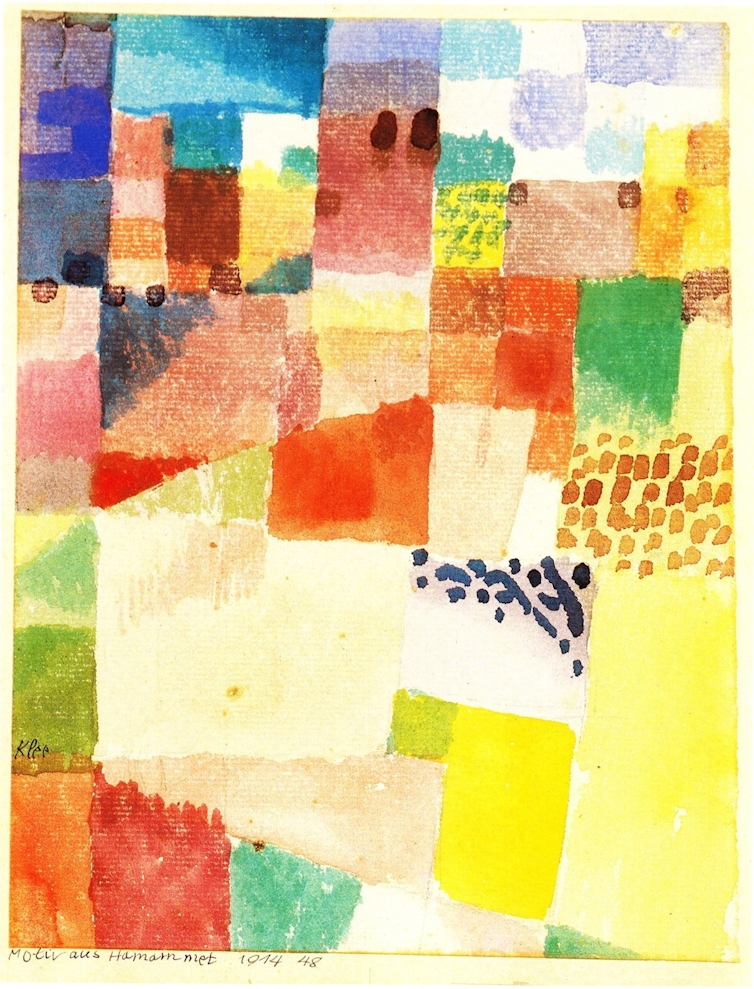

It was on his famous trip to Tunisia in April 1914 that Klee painted Hammamet with Its Mosque, now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Travelling down the east coast of the Maghrebian nation with two artist pals, August Macke and Louis Moilliet, the trio used lightweight watercolour kits and sketching blocks to record their impressions.

Tunis, St. Germain, Hammamet and the holy city of Kairouan became the sites of their collaborative visual enterprise.

Klee had recently been in Paris to visit Robert Delaunay, the artist who converted Picasso’s and Braque’s austere version of Cubism into a lyrical interplay of coloured squares and triangles.

Klee adapted this language in all his Tunisian works, and it was in Kairouan, in a café at the end of a day’s painting the domes of the city, that he declared in a moment of ecstasy:

Colour and I are one. I am a painter!

Hammamet with Its Mosque, as solid in its composition of diagonals within squares as its substance is evanescent, proves him right.

Read more: Three questions not to ask about art – and four to ask instead

‘The city is magnificent’

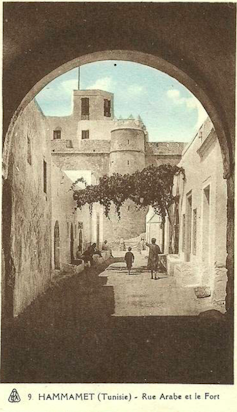

Hammamet was a small fishing port – the Hadrumetum of Carthaginian times – whose walled medina and inner fortress or Casbah still exist today. I spent three days there in 2014 on an aesthetic pilgrimage.

I was armed with maps from the Baedeker guidebook the German-speaking trio had used, postcards of the town dating from 1905, and the delightful diaries in which Klee wrote:

The city is magnificent, right by the sea, full of bends and sharp corners.

Hammamet’s medieval mosque, with its square minaret, crenellated muezzin’s gallery, and flagstaff at 45 degrees, is depicted in Klee’s watercolour with surprising accuracy.

My eyes told me as much, as did the vintage postcards. But one building was missing: Klee’s right-hand tower with its wine-coloured windows. There was nothing in today’s cleaned-up Casbah that corresponded to it.

And why, I asked myself, did the painter embellish the foreground of buff and pink triangles with star-shaped forms and green stripes?

My general thesis, in contrast to scholars who saw Klee as an abstractionist who used free invention in making his coloured pictorial tapestries, was that Klee (and Macke) used “real” elements from the observed world to fuel their plastic inventions – savvy combinations of the observed, the supposed and the superposed.

‘Archives of the planet’

Through a painstaking sifting of photographic evidence, I learned that from around 1910 until Tunisian Independence in 1956, Hammamet’s Kasbah was surmounted by a two (and then three) storey blockhouse called the “poste optique”, or optical station.

Since 1881 Tunisia had been a French Protectorate. With war looming, the French army set up a flashing optical telegraph using towers with a clear line of sight up and down the coast.

Hammamet’s new poste optique was photographed by a visiting French officer, a Lieutenant Klipfel, in 1910.

But this account of Klee’s image was incomplete because the minaret and the poste optique stood over 100 metres apart. Did Klee bring the two towers together artificially, using a painter’s creative license? That would hardly be unusual, landscape painters having done as much, from Claude Lorrain in the 17th century.

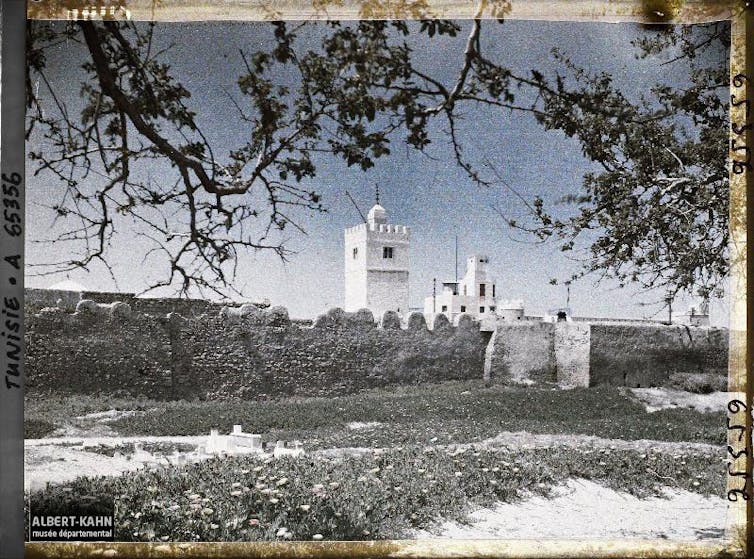

A chance discovery at the Musée Albert Kahn, outside Paris, provided the explanation.

Albert Kahn was a wealthy French philanthropist who from 1909-1931 sent photographers to 50 countries around the world to form the “Archives of the Planet”, using the new technologies of colour photography and film.

Kahn’s most prolific opérateur was Frédéric Gadmer, who on April 26 1931 visited Hammamet and took three colour photographs – two from the beach, and the other beyond the crumbling walls of the medina. This last view brought together the minaret in the centre and the poste optique well behind it.

In the foreground is flowering ground-cover and a few low-lying gravestones: the start of the Hammamet’s sandy Marine Cemetery which still stands today.

Painter and photographer had found the same motif – the floral and the ancient with a spice of modern – in their rambles around Hammamet.

Pre-war avant-garde painting

This snippet of art-historical research convinced Michael Baumgartner, former curator of the Paul Klee Foundation, that Klee was more concerned than we knew with the architectural substance of this culture which he so admired.

Indeed from this perfectly-balanced, whimsical sketch – which he cut up at home, gluing the bottom red strip to the top and providing a handwritten title and date – Klee derived a series of three increasingly grand compositions.

These were Motif from Hammamet, Abstraction of a Motif from Hammamet and On a Motif from Hammamet.

The four of them together comprise one of the great moments of pre-war avant-garde painting.

As a child I admired Klee, who was himself one of the first modern artists to admire child art. The apparent simplicity of Hammamet with Its Mosque, this little picture with a monumental impact, belies a complex history of cross-cultural encounter.

Roger Benjamin receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.