It’s 1 am, and I’m mindlessly scrolling the internet—my go-to pastime when insomnia hits. Then, a particular comment on TikTok stops my thumb in its tracks. “Fatherless behaviour,” reads a video of a woman dancing. That’s it. Just dancing. Just existing.

The comment hits me in a way that I wouldn’t have expected it to - personally. I have been slutshamed my entire life and I also happen to be estranged from her father, so it’s terrifying to know how little I’d have to do to be dehumanised by men on the internet.

It’s terrifying to know how little I’d have to do to be dehumanised by men on the internet.

Beth Ashley

It’s easy to brush this off as the behaviour of a few trolls, but this wouldn’t be true. The “fatherless behaviour” tagline that appears all over social media is just a small part of a wider problem. It’s hard to scroll anywhere, any time, without seeing a brazen attack on a woman for her sexual behaviour or perceived sexual behaviour. What made this woman appear “fatherless” was “dancing for attention” in a top that showed her cleavage. How little do women have to do to be accused of being promiscuous and then vilified for it?

What shocks me most about the way the internet has materialised slutshaming into a trend is the way it encapsulates my secondary school experience from 16 years ago. Born in 1997, I’m on the cusp of being a Millennial and Gen Z. That means I wear mum jeans and cringe when I hear people say “doggo”, but I also love Friends and remember what the world was like pre-internet.

With a foot on each side, I’ve watched, participated and been a victim of two different generations of slutshaming - they’re not that different at all, and that’s what makes it so horrifying.

I’ve watched two different generations of slutshaming - they’re not that different at all, and that’s what makes it so horrifying.

Beth Ashley

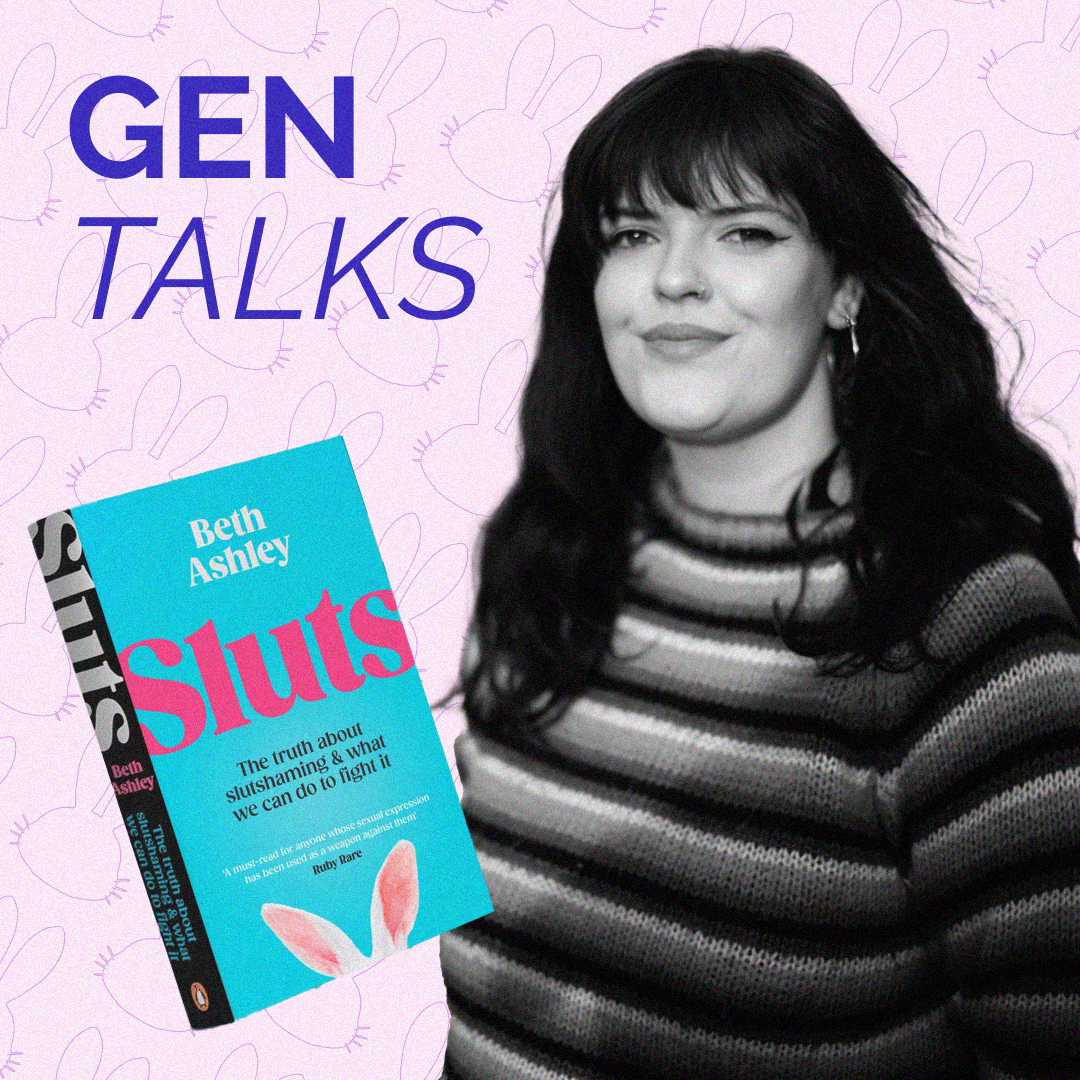

When I was researching my book, Sluts: The Truth About Slutshaming & What We Can Do To Fight It, I realised many people wrongly assumed slutshaming was unique to the early noughties. I grew up in the early to mid-2000s against a backdrop of lad mags, Britney Spears being routinely questioned about whether she was still a “virgin”, and Paris Hilton being slutshamed for a leaked sex tape she didn’t consent to. By the time I got to secondary school, The Jonas Brothers were proudly flashing their purity rings. At the same time, Jordin Sparks implied women who don’t wear promise rings were ‘sluts’ during an awards show, and The Inbetweeners was airing, where slutshaming was a plot device. This—by no coincidence—was also when I was slutshamed by family members, boys at school, and even by a teacher.

Slutshaming was an undeniable part of 2000s culture, but it never truly went away. It just became less acceptable to be so obvious about it, particularly after the arrival of mainstream sex-positive feminism. So, it became more subtle.

Slutshaming headlines may appear less, but that hasn’t stopped people from my generation asking me what my husband or my dad thinks about the career I’ve built from talking about sex. It hasn’t stopped men I’m not even interested in from telling me my sexual history is too colourful for them to be comfortable with. It hasn’t stopped friends from trying to control how much cleavage I display on nights out.

Looking around at my peers and the slutshaming we’ve faced, we may be the worst generation for sex positivity yet.

Beth Ashley

It might be that subtlety that led people to believe the myth Gen Zers are the most sex-positive generation. There’s this idea that those of us born after 1997 are politically progressive, left-leaning and empathetic. Political engagement doesn’t automatically account for a positive sexual outlook. Looking around at my peers and the slutshaming we’ve faced, we may be the worst generation for sex positivity yet.

A study found that both men and women are put off dating people who have had a “promiscuous” sex life, which they define by a lot of sexual partners. My generation obsesses over “soul ties” - a concept that has 437.4 million views on TikTok and is essentially a rehashing of evangelical purity culture discouraging women from having too much sex, lest their soul split like a Horcrux. We’re also the generation dubbed “puriteens” who’ve brought a fascination with abstinence back into the mainstream and complain about there being “too much sex” on TV. Not sounding so sex positive, is it?

Now, my generation is even ditching the subtlety. Watching women and girls be called sluts, whores, and fatherless and told they are “for the streets” over behaviour as benign as dancing, wearing certain clothing or enjoying certain types of sex makes me feel like we’ve slipped through a portal and allowed slutshaming to be loud again, rather than something that happens behind closed doors. History is repeating itself. Low-rise jeans are back in fashion, David Cameron is back in politics, and blatant slutshaming is once again normalised.

Sluts: The Truth About Slutshaming & What We Can Do To Fight It by Beth Ashley (Penguin Random House) is published 9 May