I can’t remember if I first met Judy Woolcot on the TV screen or in print: the two versions have cohered into a single entity. The television series of Ethel Turner’s Seven Little Australians first aired in 1973, so if I met her on-screen, it must’ve been via re-runs.

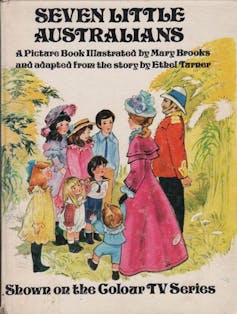

I know my mother’s paperback copy of the novel featured a still from the series on its cover: a family portrait — Meg, Bunty, Baby, Nell, Pip; the General in a nightshirt, clinging to his young mother. The ultra-Victorian Captain Woolcot, played by Leonard Teale, his chin jutting out so precipitously that it threatens to pierce through the picture. And Judy, with bundles of shoulder-length hair, perched on a sofa arm, seeming somehow too big, too angular for the frame.

Seven Little Australians was published in 1893 and tells the story of the Woolcot family: seven children, running semi-wild in the rural outskirts of Sydney, overseen by their generous young stepmother, Esther, and military-man father, Captain Woolcot. Judy, the second oldest, aged 13, is a focal point of the tribe of children.

What is it about Judy that makes her my favourite character? By the time I read Seven Little Australians, I had already met Anne of Green Gables and the stable of Little Women sisters. I had probably just opened the chocolate sampler box that was the Bennet girls. So why not Anne Shirley? Why not Jo March? Why not Elizabeth Bennet?

Read more: Little Women at 150 and the patriarch who shaped the book's tone

‘Bone-true’ authenticity of self

For one thing, Judy was solid. You could trust her with an axe, a rope, a river. She was not, like Anne Shirley, a red-headed scrap of a thing, for whom accidents were always just waiting. She was not, like Jo March, inhabiting a secret, interior writer’s life. She was not, like Elizabeth Bennet, riveted to the question of appropriate marriages.

You could rely on Judy, in her boots, stomping across a paddock, cutting through the vanities and inanities of 19th-century life. She was fearlessly outwards-facing, and deeply honest: a “wild, unquiet subject” with a “strongly expressed scorn for equivocation”. Her honesty was the noble type of honesty that came, not from assiduous avoidance of lies, but from a bone-true authenticity of self.

She was also Australian. She spoke in an Australian accent (in the series and in my head). Her trees were my trees: gum trees. Although Seven Little Australians is set in Sydney in the late 1800s, the sky that sheltered her was the sky that sheltered me; the hot, scruffy dust was the hot, scruffy dust of my childhood. The bird calls were from bell birds and whip birds, way up high in impossibly tall trees with names like ironbark: trees that were very hard to cut down and fatal when they fell.

Anne could get knocked off her perch with a mere shake of a tree branch (or of her orange braids); Jo and Elizabeth could fall in love at any moment and waft away from their own centres. But not Judy. Judy was unassailably in and of herself. And only Judy could do that gravest of things: only Judy could die.

Read more: Anne of Green Gables goes to war

Robustly competent, yet vulnerable

Re-reading Seven Little Australians, I discovered that the image I have of Judy’s physical sturdiness is not borne out by the text. Turner tells us “she was very thin, as people generally are who have quicksilver instead of blood in their veins”. Her thinness, I realise now, is code for her fragility, which runs like a weave through the novel.

When she runs away from boarding school, walking 70 miles and sleeping rough, she suffers for her adventurousness; she is found in the stable loft, coughing blood into a handkerchief — a signal moment of terror in any 19th-century narrative.

When the children conspire to earn their father’s favour, Judy doesn’t wait on him or sew for him like her sisters: she mows the lawn, with a scythe. It is this hardiness of hers, her ability to wield a scythe, that explains the robust competence that is my image of her. Yet it also reveals her precariousness: she sweeps the “abnormally large scythe” back and forth in long, dangerous arcs, “decapitating a whole army of yellow-helmeted dandelions” while her father watches on in terror.

I’m struck, as an adult, by Captain Woolcot’s recognition of his daughter’s vulnerability. “Be careful of Judy,” her mother had said on her deathbed, and thinking about Judy’s future gave her father “an aggrieved kind of feeling”:

That restless fire of hers that shone out of her dancing eyes, and glowed scarlet on her cheeks in excitement, and lent amazing energy and activity to her young, lithe body, would make a noble, daring, brilliant woman of her, or else she would be shipwrecked on rocks the others would never come to, and it would flame up higher and higher and consume her […] Judy was stumbling right amongst them now, and her father could not “be careful” of her because he absolutely did not know how.

There is a terrible modern tragedy in this: the father’s sensitive awareness of his daughter and complete incapacity to nurture and protect her. Judy is both equipped to conquer the world and ill-equipped to survive it.

‘The first time I wept reading a book’

Judy’s death was the first time I wept reading a book. I knew her death was coming: I had watched it on TV. Watched her dash to save her baby brother, watched the enormous tree branch creak and fall, trapping her body beneath it. Still, I wept. I kept hoping the book would somehow reverse the tragedy of the television version: rewrite it, reanimate Judy. But no, Judy dies – as obstinately and heroically as she lived.

And in her death, how honest and modern she remains; wholly absent of any stoic, religion-inflected martyrdom you might expect of the period. She’s a frightened child, in a hut, feeling the light fall away. “Oh Meg, I want to be alive!” she says frantically. “How’d you like to die, Meg, when you’re only thirteen!” This stricken cry cut through my childhood.

I didn’t cry this time, but I did feel sobered and still and, at least for a few moments after finishing, very still. I was right to remember Judy. Judy was a reminder of how to live, how to be in the world, which is “always in a perfect fever of living”.

By virtue of her death, Judy has a gravitas that none of her fictional contenders possess. Her mortality is the very point of her being, the point of her character.

“Judy!” Pip said, in a voice of beseeching agony. But the only answer was the wind at the tree-tops and the frightened breathing of the others.

Edwina Preston has received funding for her own creative work from Australia Council for the Arts and Creative Victoria. She is the recipient of a Research Training Scholarship and Dean's Excellence in Research Scholarship at the University of Melbourne. She was the recipient of the 2020 Felix Meyer Creative Writing Scholarship and the Helen Macpherson Smith Scholarship for female researchers.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.