Mention ‘modulation’ to a computer musician and their hand will most likely reach for the nearest soft synth or keyboard mod wheel. On the theoretical side of music, though, the term refers not to the LFOs in your synth, but to a shift in the key of the music itself - in other words, a key change.

Any piece of music has at its heart a sort of ‘tonal centre’, no matter whether you’re dealing with a simple, one-chord groove or a complex symphonic masterpiece. The tonal centre is the base key that you feel as the music is playing - the sense of where the ‘I’ chord or ‘home’ is.

When we modulate to a different key, that tonal centre changes.

There are many possible reasons for doing this, but key changes are usually used to heighten the sense of urgency or resolution in a piece, as if you’re rounding the final bend into the home straight of a race.

They’re also useful for injecting a new flavour into a progression that, at that difficult point two-thirds of the way through a track, might have worn out its welcome.

From the standpoint of evoking a surge of emotion, the semitone shift on the final chorus (or ‘trucker’s gearchange’ modulation, as it’s also known) is now a stalwart of the romantic ballad, particularly favoured by certain stool-sitting boy bands.

The main challenge faced when modulating from one key to another is how to link the keys in a way that doesn’t sound jarring or abrupt, but creates a smooth transition almost as if the listener is not aware of it until after it’s happened.

So, with that in mind, in this month’s Easy Guide, we’ll focus on a couple of different ways in which this can be achieved. See ya later, modulator!

Step 1: Here we have a I - V - IV - V progression in C major, giving us C - G - F - G. We want to keep the same progression but change its key up a semitone to C# major (C# - G# - F# - G#). So how do we get from one to the other? There are a variety of methods, the most basic of which would be to use the ‘trucker’s gearchange’ and jump into the new key with no preamble.

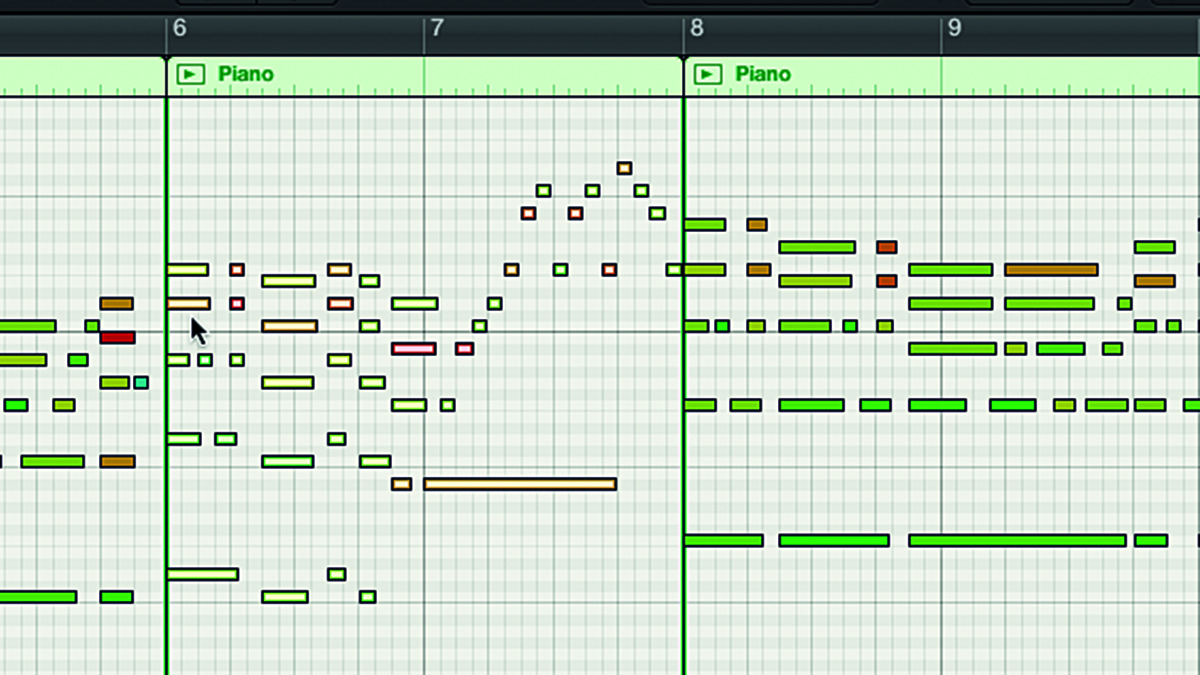

Step 2: This involves simply copying the progression, pasting it into the following bars and moving all the freshly pasted notes up by a semitone. So our chord progression goes C - G - F - G - C# - G# - F# - G#. This is a bit of a cliché, though, and while it certainly works, it has become somewhat frowned upon in credible music circles!

Step 3: A more sophisticated way is to ‘set up’ the modulation by placing the new key’s dominant (V chord) just before the change happens. The dominant chord in the key of C# major would be a G# major chord (G#-C-D#). We replace the last G major of the first section with that, giving us C - G - F - G# - C# - G# - F# - G#. This is called an applied dominant modulation.

Step 4: We could also modulate by using a pivot chord, which is a chord shared between the old key and the new one you’re modulating to. In this example, we have an eight-bar section that grooves along nicely in the key of D major. (D - F - G - D - F - G) Note that the second chord, F major, is actually outside of the key of D major, but this won’t affect our example.

Step 5: We want to shift the key up a whole tone to the key of E major. To find which chords are shared between the old key and the new key, we need to look at the basic triads formed by both the D major and E major scales. D major contains D, Em, F#m, G, A, Bm and C#dim.

Step 6: The harmonised E major scale, on the other hand, contains the triads E, F#m, G#m, A, B, C#m and D#dim. From this, we can see that the two scales have two chords in common: F#m (which is the iii of D major and also the ii of E major) and A (the V of D major and the IV of E major). Either of these could be used as a pivot chord to modulate from D major to E major. Let’s try it out.

Step 7: To put this into practice, we first need to repeat our eight-bar section to form a 16-bar section, then transpose the second eight bars manually from D major to E major by selecting all the notes in the musical parts and raising their pitch by two semitones. The resulting chord sequence in the new section is now E - G - A - E - G - A.

Step 8: What we have now is a trucker’s gear change as the track plunges headlong into the new key at the start of bar 9. To avoid this, we need to transform the G chord at the end of bar 8 into a pivot chord. Let’s try the F#m first. We change G major (G-B-D) to F# minor (F#-A-C#).

Step 9: On playback, this works but sounds a bit jarring. Shifting the low F# note of the F# minor up an octave helps somewhat, as it brings closer together the notes of this chord and the one that follows (a practice known as ‘voice leading’). Even with this smoother transition, however, it still doesn’t sound as natural as it could.

Step 10: Instead, let’s try the other pivot chord candidate, an A major chord (A-C#-E). This works better, as not only is the A chord common to both keys, it’s actually used in the progression in the new key. As a bonus, it’s the IV of E major, so we now have a plagal cadence (IV-I) setting up our key change.

Step 11: Lastly, here’s a more complex example of a modulation that shifts up a whole fourth over a series of chords from C major to F major without using a pivot chord. We start with our original chord progression of I-V-IV-V (C - G - F - G), maintaining a C in the bass throughout. For the next section, we transpose the progression up 5 semitones (F - C - Bb - C).

Step 12: A two-bar section filled with new chords bridges the gap. The first bar revitalises the existing key using the ii and I chords (Dm - C). This sets up the change to the Bb in the second bar, which we’ve picked because it’s the IV chord of F major. We then resolve the Bb to the new tonic of F major with a plagal cadence (IV - I). The new key has now been firmly established.

Pro tips

Circle of fifths

Modulations involving pivot chords tend to work better between keys that are close together in the ‘circle of fifths’ (C-G-D-A-E-B-F#-C#-G#-D#-A#-F-C-G…). For example, A major can be modulated easily to E major, but moving between F# and C will be far tougher. Closer notes are more likely to contain similar numbers of sharps or flats, and thereby have more chords in common that might be used as pivot chords.

Cadential confirmation

For a modulation to work effectively, it needs to establish the new key properly so that the listener perceives the tonal centre of the music to have changed. To help with this, try to make the tonic of the new key occur on a strong beat, preferably the downbeat of the new section. Also, if the tonic of the new key is preceded by a V chord in the same key, this will result in a perfect cadence, further reinforcing the new tonality in the mind of the listener.

Recommended listening

The Police - So Lonely

The first half of this smash is in C major and follows a I-V-vi-IV progression for both verse and chorus sections, so when the end of the second chorus comes around, Sting and the lads can be forgiven for wanting to change things up a bit.

This they do by transitioning into a guitar solo over the same I-V-vi-IV progression, now in D major, that holds fast until the end. When the vocals come back in for the outro, you’d never know it had changed key.

Dexy’s Midnight Runners - Come On Eileen

Kicking off with an intro section in F major, the first verse modulates to C major via a Csus4 chord. The first chorus then rises a whole tone to D major after which, unusually, we’re back into C major for verse two, after a two-bar tag section that consists of a pedalled A major chord.

This is one pop hit that managed to eschew the final trucker gearshift chorus key change, instead opting for a more highbrow 1-2-1-2 kind of approach.