Brilliant. Inventive. Devilish.

This is how 15-year old Jean-Baptiste Forqueray (1699-1742) describes the music that his father Antoine (1672-1745) draws from the viol, aka viola da gamba. The same words could be applied to this novel, a brilliant read inventively devised by Adelaide’s Michael Meehan, but somewhat devilish to review.

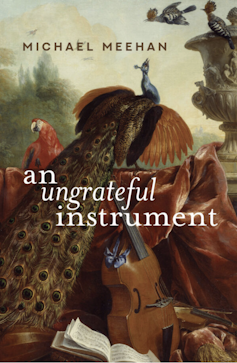

An Ungrateful Instrument – Michael Meehan (Transit Lounge)

Because, although music often tells stories, this story tells music. By which I mean that it works contrapuntally, careering ahead but also looking back and catching itself up, complicating and enhancing itself via reversals and repetitions and new motifs, never short of a theme to be introduced and played on.

I invite you to look at, listen to and enjoy this extract from the first chapter of this book, written by Charlotte-Elisabeth, purportedly Jean-Baptiste’s younger sister:

… I can tell of how the boy creeps from the house in the first light of dawn, his viol swathed in thick canvas. Of how he steps through the drifts that lead down to the river, his footsteps first to break the newest fall of snow.

He steals down to a clearing by the bank, to a seat on a toppled sycamore. He draws the viol from the canvas and opens its music to the air. The first sounds moan and clash, as though in sorrow, but then reach out, testing the silver spaces of the frozen river, the keening of the breeze that troubles the highest branches, the muffled sound of the waters that move deep below the ice.

He begins to play. A new kind of music. Not a music he has ever learned. Not a music to be played indoors, to be played within his father’s hearing. He listens closely, blending his music with all he hears around him. Chasing the rhythm, not quite yet a rhythm. Seeking a motion to bind the drip, drip, drip of melting snow, to catch the fractured melodies that run through the chill boughs above.

He drums his fingers on the belly, tracing the hiding harmonies, the matching rhythms of water, wind and trees. He draws from the frozen river a music that was there before him, a music that was there long before his father, before the first growth of his instrument, the woods through which he plays.

The prose may be unapologetically poetic, but the narrative itself is vivid and lively, sometimes even quirky, though its origins are firmly based in the history of French music. Forqueray père and, later, Jean-Baptiste, began their careers as child prodigies during the 70-year reign of Louis XIV, and in time overlapped as official court musicians.

Read more: Fornication, fluids and faeces: the intimate life of the French court

Their fictionalised story is written down by the above-mentioned Charlotte-Elisabeth, who does not speak but whose role is in every way central. When she was a child and learning to play the harpsichord, her father was determined to turn her into a prodigy as famous as her brother: one day, she too must play at court.

To this end he tries to thrash her into learning, as he’d successfully done with his son; but in contrast to her brother, Charlotte-Elisabeth rebels. Her creative life will be her own choice, not her father’s.

When she is seven, he inflicts on her a particularly savage beating, yanking a clump of her hair out, striking her with his bow until it breaks, and shutting her in her room for several days “to be starved into music”. Instead, Charlotte-Elisabeth makes a thrilling discovery: silence is her friend and consolation. When she is let out, she chooses never to speak again.

Read more: Friday essay: what is it about Versailles?

Cruelty

Forever mute (but NOT deaf-mute, as the book’s front flap nonsensically claims) she is nevertheless far from isolated. Behind the curtains of the window-seat, people confide to her the things they cannot say to anyone else, not even to themselves. Within her silence she harbours “the lost truth of all their lives”; and she continues to play the harpsichord for her own personal pleasure.

The father also continues on his path, cruelty still his weapon of instruction. Teaching Jean-Baptiste, he permits only his own compositions to be used; but as he never commits them to paper, they demand endless hours at the piano, enabling the father to overwork a pupil who must reach the level he has frenziedly set.

Unfortunately, the father fails to grasp that while this standard is high enough to impress the court and garner some fame, it is ultimately constrained by his own limitations.

Jean-Baptiste is five when he first plays for the king in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, desperately uncomfortable under a hot wig and heavy court dress. Despite much applause from the audience, the father showers him with imprecations. The reader again understands what the father does not: that the son cannot rise above a teacher who has no intention of being outstripped by his pupil.

Alongside this painful histoire runs the story introduced in the quote. We now learn that when Jean-Baptiste played in the forest he was heard by an ancient luthier living in its depths; the old man’s deep and intimate knowledge of every tree – maple, sycamore, pear-wood, ebony, cherry-wood, spruce – ensures his unerring ability to select the wood best suited to a specified instrument. After Jean-Baptiste has come by a few more times, the old man offers to make him a new viol.

The ensuing story of Jean-Baptiste’s life and career as a viol-player is not without adventures and trials. He is thrown into prison, gifted by the Duc d’Orleans with a priceless if troublesome instrument known as the regent’s viol, and exiled from France; he walks to Venice and is invited to play in the basilica of the Frari. Plus much more.

Alongside his exploits run the eventful stories of the two special instruments, the “regent’s viol” and the “forest viol”; and also those of two girls, Jeanne and Marie-Rose, both musicians, who constitute Jean-Baptiste’s romantic and conjugal life.

In the end, everything in this engrossing and beautifully presented novel contributes to one ultimate message. Music and Love should never just respond; they must both create, using the human energy that is poured into them.

Judith Armstrong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.