A hulking eastern lowland gorilla glowers from his jungle lair as a photographer – just metres away – leans in, lifts his camera, and steadies the shot.

Click!

The image of the extraordinary encounter will be used to promote tours to the German government-funded Kahuzi-Biega National Park, a vast rainforest in Africa’s Democratic Republic of Congo, and home to the critically endangered gorilla species.

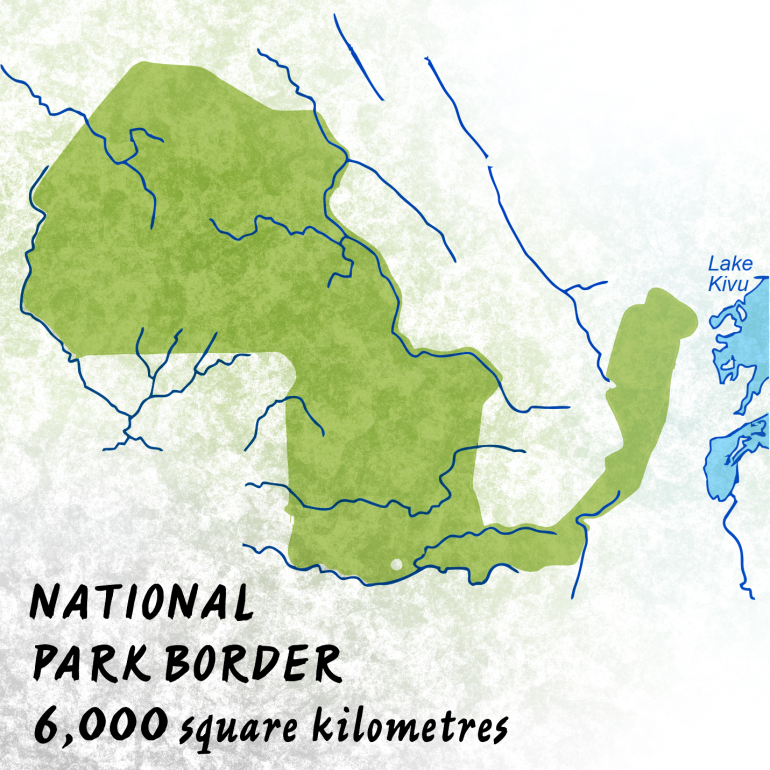

Park officials say that revenue raised by such safaris helps fund conservation efforts there – an important step as the gorilla population dwindles. Only 125 of the animals are now believed to live in the 600,000-hectare (1.5-million-acre) Kahuzi-Biega park. According to the World Wildlife Fund, that reflects a more than 50 percent reduction in the eastern lowland gorilla population since the 1990s.

Through a clearing in the jungle, the photographer leans forward again. He takes another shot. And another. They are remarkable memories of what one of the park’s visitors called a “spectacular but terrifying” experience that left her “hyperventilating” after standing inches from a silverback.

In fine print, tour operators warn of potential “violence and instability” in the region. But safaris into the park carry a veneer of sophistication. One operator promises a “luxe” experience, touting “adventure with a glass of wine” on the gorilla-spotting tours.

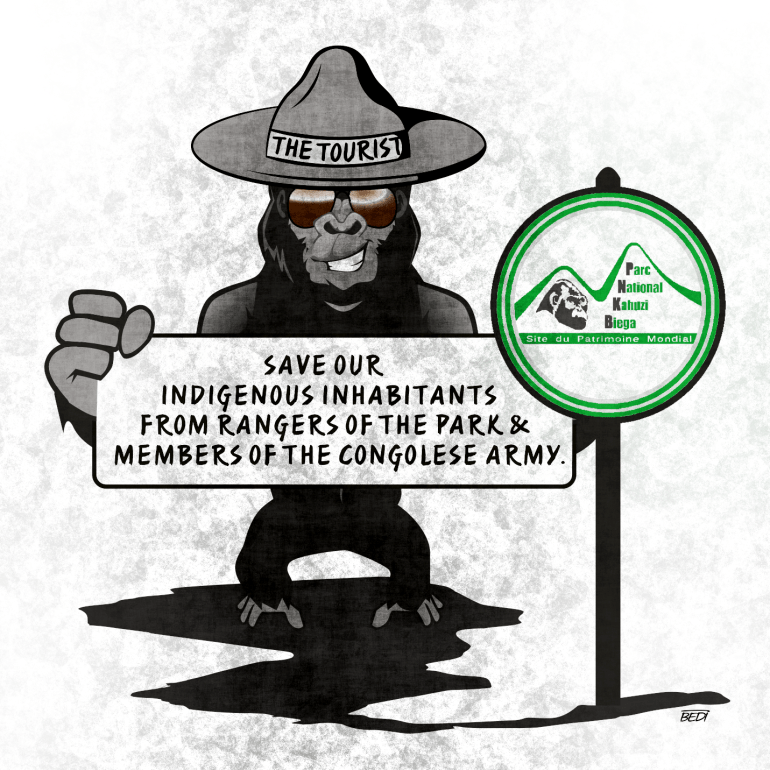

None of the brochures pointing to the splendour of the UNESCO-listed Kahuzi-Biega National Park, though, mention a dark human drama taking place under the same rainforest canopies. An organised campaign of violence, observers say, is under way to clear the world-famous park of its Indigenous inhabitants.

Operations since 2019 have allegedly involved a coordinated campaign of gang rape, murder, and ethnic cleansing. And those responsible, according to American journalist Robert Flummerfelt, are rangers from the park itself, working alongside members of the Congolese army.

Flummerfelt, who has spent many years as a journalist in the DRC, says the violence has been directed at the Batwa community, whom he says park officials are trying to evict to create the fiction that the park is an “unpeopled wilderness”.

“Indigenous people are therefore left with the impression that – at the tip of the bayonet – an arrangement is being imposed in which their land is reduced to mythic ‘wilderness’ to be enjoyed by the foreign tourist and the conservationist expert,” Flummerfelt said.

“Thus, valuing the wealthy, usually the white tourist over the impoverished Indigenous community member who has inhabited the ‘wilderness’ for millennia.”

In a report commissioned by the human rights organisation Minority Rights Group and titled ‘To Purge the Forest by Force’, Flummerfelt wrote that the campaign has involved whole Indigenous villages being torched. Working with a Congolese researcher, he said he found that at least twenty Batwa had been shot or burned to death.

Flummerfelt told Al Jazeera he had seen evidence of those “heinous atrocities” when he visited villages immediately after they had been attacked.

“The villages were literally still smouldering and the blood still drying on the leaves,” he said.

He gathered photographs of mutilated corpses, which he believed were “designed to terrorise this community into staying off of its ancestral lands”. The photographs, which have not been independently verified by Al Jazeera, show several men who’ve been shot and bayoneted to death. At least one body is depicted with a series of deep machete slashes across its torso.

Flummerfelt said that in July 2021, he sent emails containing a preliminary report on the atrocities to the Congolese government and to the German government partners involved in the park’s operations. Those partners included the KfW development bank, the GFA Consulting Group and the GIZ aid agency.

Five days after Flummerfelt sent those emails, the German ambassador to the DRC, Dr Olivier Schnakenberg, paid a visit to the park, posing for photos with members of the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN), the same park authorities identified by Flummerfelt as being responsible for the gang rapes and killings.

A news release later published by park authorities noted the ambassador “paid tribute” to the park’s guards, congratulating them “for their dedication despite the difficulties” of their mission, and insisting that “their sacrifice deserves encouragement”.

During his visit to the park, the ambassador was also photographed with a staffer of the GIZ Aid agency, the same group that had been alerted to the alleged atrocities less than a week earlier but which had, at that stage, not acknowledged receipt of Flummerfelt’s accounts of the violence.

Several months later, the GIZ aid agency acknowledged that they had, in fact, received Flummerfelt’s email, saying that they had been attempting – without success – to verify the violations alleged within it.

The aid agency also said that following the ambassador’s visit to the park, they “organised a meeting between the ambassador and representatives of the Indigenous population as well as representatives of national NGOs which advocate for the rights of the Indigenous population.”

A German government-funded inquiry

Flummerfelt’s preliminary report did nothing to stop the apparent campaign of violence against Batwa villagers.

Reports suggest that another attack was launched on November 11, 2021, destroying all villages in the park that had been occupied by Indigenous people.

Flummerfelt followed his preliminary accounts of the violence with his more comprehensive ‘To Purge the Forest by Force’ report, which was published in April this year. That document increased pressure for an investigation, finally prompting the German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), operating through the Hamburg-based GFA Consulting Group, to establish a Commission of Inquiry into Flummerfelt’s claims.

The Commission would include representatives of the GFA Group – which describes itself as “an ever-learning organisation” which seeks “to improve the living conditions of humans worldwide” – as well as delegates from the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Remarkably, the man chosen to lead the Commission was George Muzibaziba, the official in charge of Human Rights at the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN), the government agency that runs the Kahuzi-Biega National Park.

“Although the Germans funded and organised this investigation, on-the-ground ICCN staff coordinated and led everything. In effect, ICCN was investigating itself, an enormous conflict of interests,” Flummerfelt told Al Jazeera.

Audio recordings from the inquiry, leaked to Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit, reveal Muzibaziba telling one witness that Flummerfelt “wrote the report that has smeared our country so much and smeared our park so much”.

Flummerfelt said he had initially agreed to sit on the Commission but later withdrew because he believed it had “flagrantly violated every applicable ethical and moral standard and apparently endangered the lives of the very people to whom [he has] the greatest responsibility”.

He described the Commission as “disastrous”, and said it “flatly cannot be treated as a serious effort to investigate”.

Flummerfelt’s Congolese researcher, who we are not naming for safety reasons and who managed to remain anonymous throughout the course of his research, was asked to give evidence to the inquiry, but says he immediately detected hostility from the group.

“From our first meeting we had with the Commission, all they wanted to do was show how everything we had done was a bunch of lies,” he told Al Jazeera.

The researcher said that he was told that, “if they don’t find 100 percent of what we had published, that means we are a bunch of liars”.

He said that, though he had asked to remain anonymous, details of his identity were leaked by the Commission.

Death threats

According to two independent sources with direct knowledge of the matter, secret meetings were then held between ICCN officials, guards, and sympathetic local Indigenous people in which a plot was hatched to kill the Congolese researcher and Flummerfelt.

The researcher said that park guards later went to his home on what he believed was a mission to murder him.

Along with Flummerfelt, he has now fled and both men remain in hiding.

“I decided to leave everything, leave my job, leave everything, in order to save my life,” the researcher said. “I am afraid that, as soon as we go back, these people will kill us. I am certain that the Kahuzi-Biega park guards will kill us.”

Leaked minutes from a meeting of ICCN park guards, held following Al Jazeera’s notification to the ICCN of the alleged death threats stemming from the Commission, gave further detail on plans to hunt down Flummerfelt and his colleague, revealing that efforts to locate the pair were being organised by the recently-ousted ICCN Park Director, De-Dieu Bya’ombe.

The German newspaper Die Tageszeitung had earlier reported that internationally-funded training programmes for park guards in Kahuzi-Biega had been conducted by Israeli private military contractors, staffed by former Israeli military commandos who had combat experience in Lebanon.

“Even by the standards of militarised conservation,” Flummerfelt said, “this struck me as remarkable.”

According to Flummerfelt, the DRC Sanctions Committee of the United Nations Security Council was not informed of those training activities. He alleges that the failure to alert the Sanctions Committee constitutes a violation of a UN-imposed arms embargo against the Congolese government.

A history of abuse

The recent attacks against the Batwa people are the latest episode in a long history of abuse against the Indigenous community. Following Congolese independence from Belgian colonial rule in 1960, conservationist Adrien Deschryver – a descendant of Belgian’s last Minister of the Colonies – convinced the nation’s newly independent administration to expand the territory of Kahuzi-Biega, to give it the status of a national park, and to drive Indigenous inhabitants out of the area.

In the 1970s, up to 6,000 Indigenous Batwa were forced to abandon their villages. Many were resettled in poverty-stricken towns on the periphery of the national park.

Linda Poppe, from the human rights organisation Survival International, says the expulsion of Indigenous communities is a practice frequently employed throughout Africa and rooted in the concept that “we in the West know better than the Indigenous population that really has managed this land so well for generations.”

“It’s a terrible concept of conservation because it causes land theft and so much violence and suffering among Indigenous peoples who are the best guardians,” Poppe said.

“The land is their supermarket, it’s their church, it’s their pharmacy and it’s the school for their children. And if they lose this land, they lose the livelihoods and everything that makes up the social fabric and the special relation to the land.”

In 2018, after 40 years in exile, the Batwa people resettled within the Kahuzi-Biega National Park.

An account of the most recent efforts to expel them was provided by Batwa Chief Majafa, who testified before the Commission of Inquiry, sparked by Flummerfelt’s report.

“I did not just say that some people had come, that they burnt our homes down, they killed us, and they raped our women,” Chief Majafa told Al Jazeera, recounting what he told the Commission.

“But I said that it was you lot who came here, the only form of assistance you ever gave us was to kill us, to burn our homes down and to rape our women.

“After I said all that, three days later I had to flee my village after being considered a target. I received threats from the ICCN working alongside the Congolese army,” Chief Majafa said.

“They wanted to kill us so that they could erase all of our traces so that no evidence is left, and no leader can stand up and speak for the Indigenous people.”

A second Batwa leader, Chief Mbuwa, corroborated Chief Majafa’s testimony, saying that after showing the Commission’s investigators three graves, “they said they weren’t going to visit the rest of the graves where we buried the other villagers who were killed because it was going to rain soon and so they wouldn’t have the time to go see the other graves of other people killed.”

In audio recordings of the Commission of Inquiry’s fieldwork obtained by Al Jazeera’s Investigative Unit, the lead Commissioner George Muzibaziba is heard telling Chief Mbuwa that if ICCN guards and Congolese soldiers are forced to leave the area as a result of testimony he provided, then he would have to “take responsibility” for his community being attacked by armed militia groups.

In another interview, the lead commissioner told a witness that the information being provided would be “dangerous” for them. Another Commission member then interrupts Muzibaziba, saying, “George, don’t intimidate him.”

The leaked audio also appears to indicate that fellow investigator Baptiste Martin was aware that Muzibaziba was pressuring witnesses. Referring to how Muzibaziba conducts his interviews, he said “[he] threatens … and it’s a little bit in between the lines. Rather than saying ‘this is confidential,’ he’s like, ‘this is for your own security, this is for your own security.’”

The Commission’s report

The Commission of Inquiry’s report into the violence, published on June 1, cleared ICCN guards of committing atrocities, instead finding that guards had been forced to defend themselves against “armed” Batwa villagers. While acknowledging that members of the Batwa community had been killed, it wrote that some deaths occurred when Batwa villagers were used as “human shields” in conflicts between park guards and poachers. Those claims have not been corroborated.

Leaked internal documents detailing evidence gathered by Commission investigators show that the Commission’s report failed to include testimony provided by multiple sources linking ICCN park guards to alleged atrocities committed against the Batwa.

The Commission’s report acknowledged that investigators had “received reports of attempts to intimidate some of the organisations conducting investigations.” It said they “took appropriate measures, including the decision not to make public the names of sources and organisations that had contributed to the investigation.”

The Commission claimed that “consent of those interviewed” was sought for the “use of the information collected”. However, leaked audio shows that a number of Batwa sources may not have given informed consent as they were not properly told of the affiliation of members of the Commission.

Claims that the Commission undertook a “gender-sensitive approach” also appear to be contradicted by audio recordings in which members of the Commission can be heard laughing about group rape allegedly committed against Batwa women.

A ‘cover-up’

Journalist Robert Flummerfelt characterises the work of the Commission as a “cover-up”.

“If the German government is going to make a decision about whether it’s going to continue its support to the park based off of the findings of this Commission,” Flummerfelt told Al Jazeera, “then the German government is basically saying we’re content to take the findings of a violent cover up and use that to justify a continuation of the status quo. That’s simply unacceptable”.

Al Jazeera contacted all parties involved in the Commission, informing them of the allegations of death threats and witness intimidation, and inviting them to respond to those claims.

Commission head George Muzibaziba, in response to a question about whether ICCN staff were involved in killings, mass rapes and the forced expulsion of Batwa villagers, suggested that Al Jazeera “refer yourself to the published report”.

Muzibaziba denied that park guards were trying to find and kill Flummerfelt and his Congolese researcher, saying “this is very wrong”.

Muzibaziba denied intimidating witnesses, instead accusing Flummerfelt of “false claims” and of using “highly biased” methodology. He claimed not to know who the Congolese researcher was, in spite of the existence of audio recordings of his meetings with this researcher.

Baptiste Martin acknowledged having identified “risks to the protection of sources and witnesses” which, he said, are being addressed through “confidential engagement and coordination with the concerned parties”.

A spokesman for the BMZ told Al Jazeera that they are “deeply disturbed by accounts of threats and intimidation allegedly levelled against witnesses and sources by members of the Commission”, that it “has requested the Congolese side to guarantee the safety of the members of the Commission as well as any other persons concerned” and that they “will reflect on [their] continuing support for Kahuzi-Biega”.

Former ICCN Park Director De-Dieu Bya’ombe and a UN representative for sanctions in the DRC did not respond to questions sent by Al Jazeera.

The Batwa struggle continues

The two Batwa chiefs who’d been forced to leave their villages say that, despite the violent campaign against them, they are determined to return to their ancestral lands.

“The villagers say that if they must die, they will accept death as long as it’s on the land of their ancestors,” Chief Mbuwa told Al Jazeera.

“They will never flee again, even if they attacked us ferociously. We are there and we shall remain there. We will stay there as it is our land, given to us by our ancestors.”

Chief Majafa expressed the hope that all his people will resist the attacks against them by refusing to leave.

“Even if they exterminate each and every one of us, even the last villager standing would stand up for our land in Biega, the land of our ancestors.”