Women are preprogrammed to think motherhood is what they should want, and that it should feel natural when it happens. But what happens when it doesn’t? What if they don’t like who they are around their children? What if they miss their old life and who they were in it? Author Laurie Elizabeth Flynn examines motherhood through her own experience as a mum-of-four and her upcoming book ‘Till Death Do Us Part’. Here, she talks about her journey to ditching societal expectations of motherhood.

By Laurie Elizabeth Flynn

“In my early twenties, I lived a nomadic life. I modelled in Tokyo, Athens, and Paris, and when I was home I waitressed, bartended and went out with my friends. Life felt vibrant and spontaneous. The idea of being in a serious relationship, much less engaged, was not on my radar, and motherhood couldn’t have seemed more distant. Someday, maybe, but not anytime soon. Had someone told me I’d one day have four kids in four and a half years, I would have laughed in their face. But in my mid-twenties, I began dating my now-husband, and suddenly, I could picture the family we would have together when the time was right. My ambivalence toward motherhood was gone: the children I once couldn’t imagine became the children I couldn’t imagine my future without.

Had someone told me I’d one day have four kids in four and a half years, I would have laughed in their face.

We had a daughter first, followed by a son. Both were excellent sleepers and for a blissful while, it felt like we had cracked the parenting code. Then we had two more daughters, both pandemic babies. It was stressful, with constantly changing hospital rules, navigating Zoom social life, doing virtual book events in a nice dress and slippers—the only times I changed out of my threadbare sweatpants— while my husband kept the kids quiet and entertained downstairs. I mourned for the activities the kids were missing out on; playgroups, swim lessons, and toddler gymnastics. Hunkered down at home, I tried to be a fun mum. There were crafts and science experiments, but the uncertainty began to fester and with it came more Netflix and more guilt.

I missed my old self, the carefree, spontaneous girl who wasn’t beholden to anyone else.

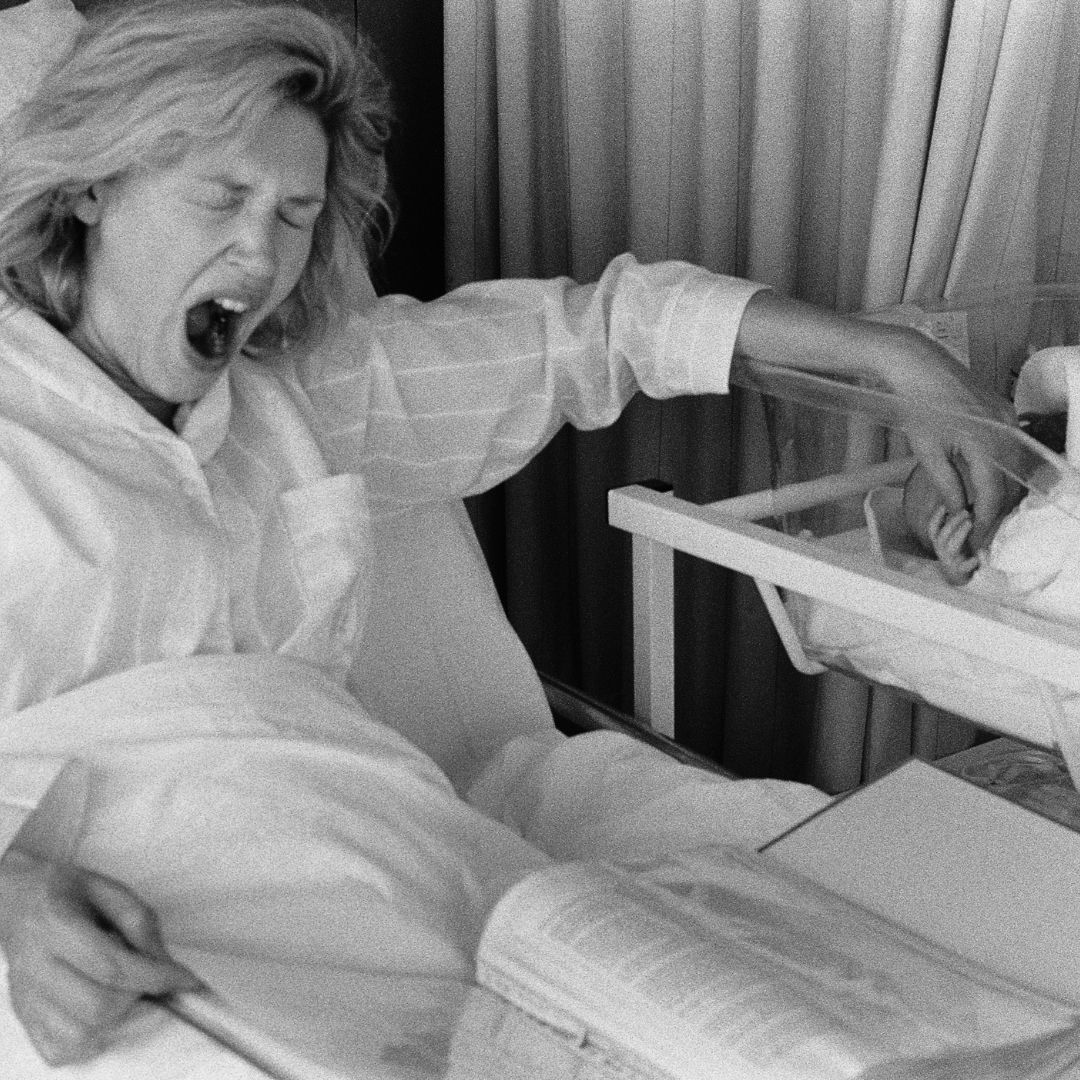

My guilt was as constant as the Netflix shows that ran in the background. Paw Patrol and Peppa Pig provided the soundtrack to our days as my husband and I attempted to work with all the kids at home—me on my next novel, which wasn’t coming together as I’d hoped. My brain felt foggy, my creativity depleted to the point where I wondered if it would ever return. I tried to keep up with crafts and science experiments, but some days, I couldn’t muster the energy, let alone imagine cleaning up the inevitable mess. I was less patient and more irritable, a version of myself I didn’t recognise or like. I felt like I was failing on both fronts, as a writer and a mother. I struggled to live in the moment and found myself wanting time to speed up and to feel less in demand. Then, I’d feel guilty for having those feelings. I missed my old self, the carefree, spontaneous girl who wasn’t beholden to anyone else.

This was when the bud of a character began to form. She was a woman who had done her best but felt trapped by the choices she had made, and their reverberations through the next generation. Enter Bev Kelly, one of the narrators of my novel Till Death Do Us Part.

At the time, I had been working on a different book, one that wasn’t coming together. It was heartbreaking to abandon that book and start from scratch on something new, but liberating at the same time—like shedding an old skin. My new book had dual narrators, two very different women—one who wants to become a mother, and another who wonders if she should have become one in the first place. The mother, Bev Kelly, questions everything about her parenting decisions and realises, too late, that motherhood may not have been what she truly wanted. She misses her old self like a long-lost friend. Writing Bev was, in a way, an escape hatch into a woman different from me but in some ways alike. I made her vulnerable, and in writing her, I made myself vulnerable. My greatest hope was that mothers reading the book would feel seen and understood.

Bev’s love for her children is a constant, but her love for herself as a mother is not. She says: “Most mothers loved talking about their children. I heard the other winemakers’ wives tell stories, their eyes shining with joy. I used to be the same way, collecting the compliments that seemed to follow us wherever we went. You have your hands full. You have a beautiful family. My hands had been full, but I had never felt less useful, less productive, less myself. Now, I felt panic instead of pride when I thought about my sons. When I considered who I had been as their mother.”

By the time the world opened back up, my own guilt resurfaced. What did I have to show for the pandemic years? I hadn’t learned a language or mastered a sourdough starter. But I did have a novel I was proud of, and four healthy, happy children I loved with every ounce of my imperfect self. I learned that I don’t have to be “fun” all the time, have a special activity planned or cherish every single moment to be the mum they need.

And Bev? Well, you’ll have to read the book to find out, but I gave her the ending I wanted her to have, the one she deserved. It’s normal to miss our old selves, but it’s important to remember that they’re still within us, never far away.”

Laurie Elizabeth Flynn is a former model who lives in London, Ontario with her husband and their four children. Her adult fiction debut, The Girls Are All So Nice Here, was named a USA Today Best Book of 2021, sold in 11 territories worldwide, and became an instant bestseller in Canada. Her second novel for adults, Till Death Do Us Part, was an instant USA Today and national Canadian bestseller, and a Good Morning America Buzz Pick. She is also the author of three young adult novels under the name L.E. Flynn.