It’s April Fool’s Day in Eagle Pass, but there’s nothing to laugh about here. On a cloudy spring evening, a dozen activists and spiritual leaders gather in a circle—just feet from the bank of the Rio Grande and a miles-long maze of concertina wire—with white carnations, daisies, and hymn lyrics in hand.

This group has come for months now to sing, pray, and toss flowers in the river. Since last year, when Texas Governor Greg Abbott ramped up border militarization in the area by placing dangerous buoys in the river, these mourners have assembled under the moniker the Border Vigil to remember the lives of those lost crossing.

The contrast here—between the U.S. and Mexican sides of the river—is jarring. On the Texas side, shipping containers form a makeshift wall that wasn’t here until a few years ago. Barbed wire tops cyclone fencing, extending almost as far as the eye can see. Shelby Park, typically a riverside gathering spot for Eagle Pass families, now looks like a fortress. Atop the shipping containers, an armed National Guard member stands in uniform, performing his imperious, taxpayer-funded surveillance. But, apart from the vigil, almost nothing is happening here. Shortly before I arrived, I’m told, a drone was buzzing over the activists.

On both sides of the río, birds sing. The peaceful sounds contrast with the military personnel and police officers. The birds flit across the river, and one lands on the tree next to me. They don’t even bother to fly through the official port of entry.

On the Coahuila side, colorful murals welcome visitors. There are more trees and, in the distance, a hike-and-bike trail. There are also three men fishing—an activity that’s not possible from where I’m standing; since the state took over the area in January, locals tell me Shelby Park is often closed to civilians, barring special permission to come in.

Every civilian in the park this evening is here for the vigil, and that’s only because they got approval ahead of time. Today, we needed permission from the Texas Military Department (TMD) to mourn migrants who drowned right here. Last week, over email, a TMD chaplain originally told one of the vigil organizers that reporters wouldn’t be allowed, but I was ultimately let in without hassle. In a later email to the Texas Observer, a spokesperson for the military department claimed: “The community continues to have access to the park, as does the media.”

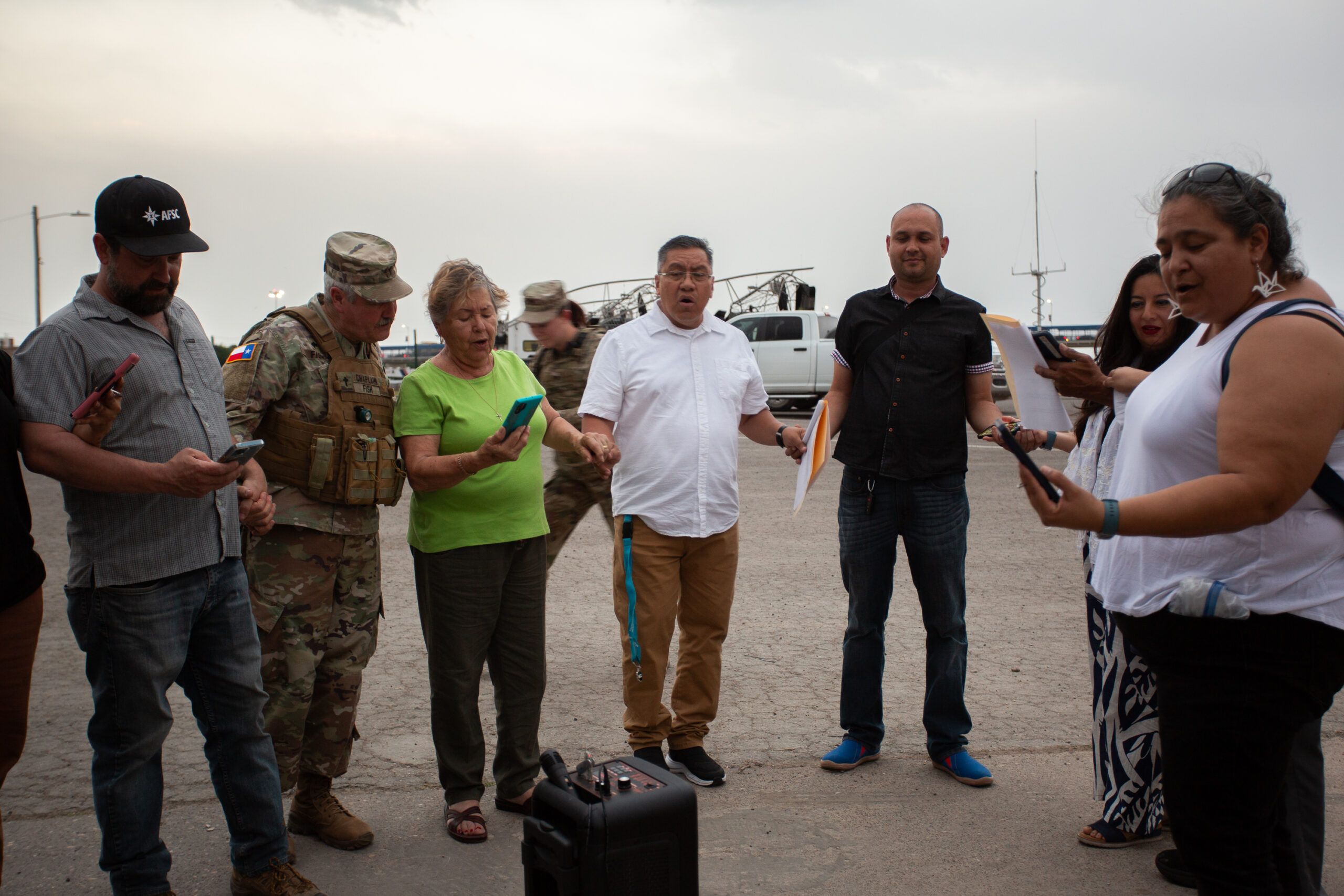

On the edge of what used to be an easily accessible boat ramp, the mourners gather to sing. Some have traveled far to bear witness here; a handful of representatives of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker group, came from Washington D.C., Atlanta, and Baltimore.

In Spanish and English, the mourners sing: “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound, que a un infeliz salvó.” They recite Bible verses about welcoming strangers, immigrants, and refugees.

“Treat the stranger who lives among you as one of your own. Love him as yourself,” Eagle Pass resident and Lutheran deacon Mike Garcia reads aloud, adding: “We want to pray for immigrants and refugees who seek a better life in our country. We pray for those who work to defend their rights.”

Julio Vásquez, a pastor at a local church, has personal experience as a stranger in a new place. He immigrated to the United States from El Salvador 24 years ago. He leads the group’s recitation of the Lord’s Prayer. “Padre nuestro, que estás en el cielo, santificado sea tu nombre…”

Amerika Garcia Grewal, one of the main organizers of the Border Vigil and Mike’s daughter, hands out white carnations and daisies. One by one, everyone walks down to the edge of the boat ramp, now overgrown with grass, where the shipping containers and razor wire meet the river. They toss their flowers in.

Two puppies, roaming the river banks, sniff our feet. Amerika says she’s seen National Guard soldiers feed these dogs and teach them tricks. But she doesn’t see them offer aid to migrants. Today, she saw guardsmen yelling at a woman and her child, stuck amid the concertina wire on the U.S. side, trying to claim asylum.

I throw my white carnations in the river, thinking of a friend of mine from the Syrian city of Aleppo. ISIS and bombs came to her neighborhood, so her family left. She’s a U.S. citizen now, but not so long ago she and her family were lost in a Turkish forest, trying desperately to reach Europe. Instead, they eventually managed to find refuge in Texas. All across the world, people like my friend, people like the mother and child yelled at by the Texas soldiers, are right now fighting their way to safety.

If you’re born on my side of the river, you’re afforded dignity—otherwise, you’re welcomed by concertina wire and border security theatrics.

After the ceremony’s conclusion, a strong wind picks up. Lightning flashes. To ward off the gale, guardsmen cover themselves with human-size, clear plastic shields.

One of the Quaker visitors points out the shields. “What could those be for other than pushing people back into the river?” he asks me.

All this—the shipping containers, shields, deadly buoys, razor wire, drones, guns—just because some people are born on the other side of a river.