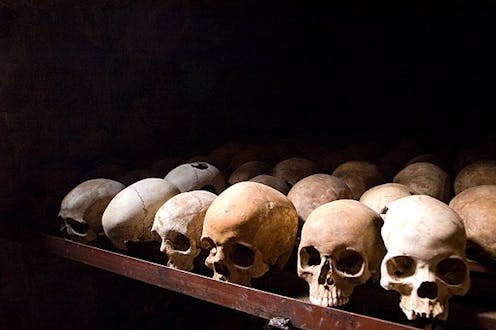

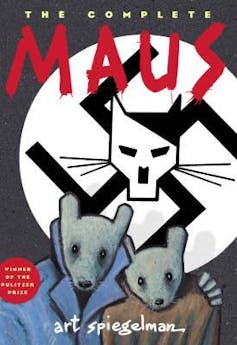

On January 10 2022, the McMinn County School Board in Tennessee voted unanimously to remove Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus from the school’s curriculum, and ban it. The board cited concerns about nudity and profanity, implicitly raising broader questions about the book’s depiction of violence.

The content of Maus is inherently violent: its subject is the Holocaust. Spiegelman based his graphic novel, which depicts Nazis as cats and Polish Jews as mice, on the experiences of his parents. Built around a father-son dialogue, Maus not only depicts the horrors they and countless others endured under Nazism, it examines how the children of survivors struggle in the wake of their parents’ unimaginable suffering.

Book boycotts and bans have a long history. More often than not, they are crudely disguised political manoeuvres. In 2012, for instance, Arizona banned Shakespeare’s The Tempest from public schools, passing a law that prohibits texts that could promote the overthrow of the United States government, promote resentment toward a race or class of people, or advocate ethnic solidarity instead of treating pupils as individuals. In a state with a large proportion of students of Mexican-American origin, the slave Caliban’s desire to overthrow his master Prospero apparently holds some kind of incendiary revolutionary potential.

The Maus ban occurred in the context of growing debates in the United States and elsewhere about what violent histories should be taught in schools and how they should be taught. But the issues it raises extend well beyond censorship and pedagogy.

How should histories of great violence, which have undoubtedly shaped the contemporary world, be represented in art – literary or other? Is there a limit to what can or should be depicted? How staunchly should authors adhere to the established version of historical events, narratives often forged by the powerful and dominant to the detriment of the defeated and the silenced? Do authors have a “responsibility” to promote accepted or official history?

Behind all of these questions is the issue of how and why we should read literature that deals with violent and disturbing material, particularly when it complicates the moral issues that material raises. What do we do when a book asks us to consider the perspective of the perpetrators and not the victims?

The tragedy of Rwanda

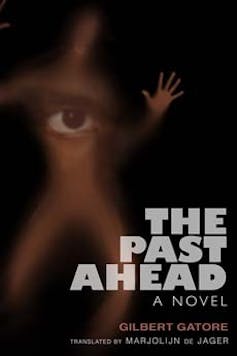

In 2008, Rwandan author Gilbert Gatore published his first novel Le Passé devant soi, which was translated into English in 2012 under the title The Past Ahead.

Born in 1981, Gatore was only a child when the genocide in Rwanda erupted. He fled with his family to neighbouring Zaïre (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). At the age of 16 he arrived in France, where he has lived ever since.

Gatore published The Past Ahead when he was 26 years old. He has said that the novel was partially inspired by his desire to reconstruct the content of a diary he had kept in Rwanda, but lost on the roads of exile. He was also inspired by another diary recounting genocide: that of Anne Frank.

Gatore’s novel is significant for several reasons. Firstly, it is one of the first to be written by a Rwandan who actually lived through the genocide. Literature written by Rwandans on the genocide had favoured the testimonial form until fairly recently. This is understandable. Their questions were too pressing, too anchored in reality, to harness the imaginary excesses of novelistic creation.

A second distinguishing characteristic of The Past Ahead is Gatore’s decision not to use terms that have become inseparable from the genocide in Rwanda. The words genocide, Hutu, Tutsi, and even Rwanda are strikingly absent from his book.

Yet there is no ambiguity about the historical episode being portrayed. The missing terms are replaced by others: civil war, massacres, killings, barbarians and moles. The novel distinguishes between those who are avec nous or de notre côté (with us/on our side) and the pays … là où (country … there where).

A third distinguishing feature of The Past Ahead is its approach to representing guilt and victimhood. The novel undermines the binary distinction between perpetrators or victims, weaving together the stories of two protagonists. The first, Isaro, returns to Rwanda, where all her family were massacred, to document the genocide, interviewing witnesses, survivors and perpetrators. The second, Niko, is a figment of Isaro’s imagination: a mute social outcast who participated in the massacres, then withdrew from society indefinitely.

Gatore does not shy away from detailing Niko’s heinous crimes, but the reader cannot help but feel sympathy and even compassion for young Niko. The novel presents him as another victim of its pessimistic tale.

Read more: In Rwanda, genocide commemorations are infused with political and diplomatic agendas

The perverse pact

The Past Ahead was well-received and did fairly well commercially for an unknown first-time author. It even won a relatively prestigious literary prize in France, the Prix Ouest-France Étonnants Voyageurs. There is no denying Gatore’s talent.

Yet The Past Ahead stirred up controversy, notably in academic circles. Its author was accused of historical revisionism and writing an unethical novel. The charge of immorality was brought on the basis of Gatore’s sophisticated blurring of the line between victim and perpetrator, and the generation of sympathy for the killer child Niko.

This representation was, for some, neither tolerable nor realistic. It established what literary critic Catherine Coquio called a pacte pervers (perverse pact) between the author and the reader.

Gatore is not the first author to have written the story of a child who kills in the context of genocidal violence in late 20th century Rwanda and Burundi. The criticism directed at Gatore’s novel appeared to have much to do with the author himself. Some critics reproached him for writing a genocidal character for whom the reader develops sympathy in order to expunge filial guilt concerning his own father, who had been accused of participating in the genocide (although the exact nature of his alleged participation is unclear).

Gatore must have known that his novel was likely to provoke strong debate. He opens The Past Ahead with a targeted warning against those seeking a neatly-defined and aligned “good” versus “bad” narrative:

Dear stranger, welcome to this narrative. I should warn you that if, before you take one step, you feel the need to perceive the indistinct line that separates fact from fiction, memory from imagination; if logic and meaning seem one and the same thing to you; and, lastly, if anticipation is the basis for your interest, you may well find this journey unbearable.

The Past Ahead muddies the waters between history and stories, making it impossible for some to see this novel as a work of fiction, rather than a manipulated version of history.

Read more: Remembrance is the most powerful weapon against genocide

Compassion for murderers?

Parallels can be drawn between Gatore’s novel and Der Vorleser (1995) by German writer, philosopher and judge Bernhard Schlink, which was translated into English under the title The Reader.

The Reader explicitly deals with questions of guilt (collective and individual), generational condemnation, and what Hannah Arendt called the “banality of evil”. It developed the theme of unresolved and perhaps unresolvable tension emanating from the inter-generational divide between those who lived through the war and those who came after, who struggle to comprehend the actions (and inactions) of their forebears. It depicts ordinary people doing terrible things.

The Reader was tremendously successful both in Germany and internationally. It has been translated into more than 50 languages and has become a set text on school and university syllabuses the world over. And like Gatore’s The Past Ahead, it has been controversial.

This is again linked to the problem of moral ambiguity. At issue is the generation of sympathy for characters who have participated, in whatever capacity, in the murder of millions of people.

The novel recounts the story of Hanna Schmitz, a German woman who is accused and convicted for her role as an SS guard under the Third Reich. Schlink presents Hanna’s illiteracy as a mitigating factor. The reader indeed feels empathy for her, identifying redeemable traits in Hanna that stand in stark contrast with her terrible actions. Once again, the novel blurs the conventional victim-perpetrator dichotomy, exposing the complexity and perhaps the inevitable fallibility of human nature.

Responses to The Reader have tended to reflect individual perspectives. German critics have defended Schlink’s novel, even applauded it, while Jewish critics have been more scathing. American and British critics have proposed both positive and negative readings of the text.

George Steiner, an influential literary critic and a Holocaust survivor, described Schlink’s novel as both “profoundly moving” and “rapidly becoming a touchstone of moral literacy”. Others have not been so complimentary. Jeremey Adler, himself the son of a Holocaust survivor, denounced the novel as an exercise in “the art of generating compassion for murderers”.

Memory and historical revisionism

No one could accuse Schlink of defending the Nazi regime. His own father, a professor of theology and a pastor in the Confessing Church, was a victim of Nazi persecution. Neither Gatore’s nor Schlink’s protagonists remain indifferent to what they have done.

But many of the accusations of historical revisionism levelled against their novels have arisen from the ways in which the subjective memories of the protagonists do not align with the accepted history. This divide between subjective memory and objective history has proved to be central to the critical reception of genocide literature.

Yet the division is problematic. For historian and scholar Enzo Traverso, the distinction between history and memory is an illusion, as history is itself a narrative process of selection:

We need to take into account the influence of history on memory itself, for there is no such thing as a literal, original and non-contaminated memory: memory is always constructed within public space, and therefore subject to collective modes of thought, but also influenced by the established paradigms for representing the past.

If we accept that the divide between history and memory is treacherously deceptive, arguments concerning the morality of representation become less pertinent. They serve to prescribe literary creativity and, in doing so, diminish the higher purpose of literature and all that it can teach us. Where else but in literature can such troubling and urgent questions be posed?

The dichotomy between subjective memory and objective history does not reflect the complexity of personal and collective representations. The distinction between victim and perpetrator is often oversimplified; it cannot account for all the nuances of responsibility. It is precisely within literary texts that these complexities can be revealed.

This is not to say that perpetrators and victims do not exist, both in history and in fiction. It is, however, to recognise that literature is a “safe” space where conventional categories – memory and history, victimhood and guilt, damnation and redemption – can be tested and negotiated. It recognises the great value of these texts, that which sets them apart from purely historical accounts.

The flexibility of literature plays a fundamental role in the cultivation of empathy, comprehension and forgiveness, the very emotions that appear lacking in the violent histories of our world. It can render the incomprehensible slightly more comprehensible and, in doing so, underscore the humanity of all.

The potential for works of fiction to make us think deeply about how we treat others, about the decisions we make and the judgements we pass far outweighs any critical condemnation on the basis of accurate or immoral representations. Readers do not have to agree on an author’s fictional portrayal, but they should defend the right to portray.

Charlotte Grace Mackay does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.