Along the bridge, the Russian soldier gripped his assault rifle tightly and aimed when a passing vehicle did not stop fast enough for his liking. Since Russia’s war against Ukraine began, there have been unusual outbreaks of political unrest in Transnistria, the Kremlin-controlled breakaway region of Moldova.

One woman said pro-Ukrainian “saboteurs” had attempted to stage an anti-Russian protest, which was quickly suppressed, followed by a larger pro-Russian demonstration. Then came a public plea from nervous authorities: no more political displays.

Across the demarcation line, in Chisinau and other Moldovan towns, fears are also mounting as the struggling country, which is among the poorest in Europe, welcomes and shelters tens of thousands of Ukrainian refugees flooding in from the war next door.

“The country is divided already,” said Daniella Calmish, a journalist at the Moldovan weekly newspaper Ziarul de Garda. “Some people are in favour, and some are against Russia. There is an information war going on.”

In a briefing with international journalists on Wednesday, Moldovan foreign minister Nicu Popescu pleaded for financial and political support. “We are Ukraine’s most fragile neighbour and our situation is complicated on all possible fronts,” he said.

Like Ukraine, this former Soviet republic has a popularly elected pro-European Union president brushing up against a significant Russian-speaking population that is sympathetic to the Kremlin and Russia’s president Vladimir Putin.

Like Ukraine, it is partly under occupation by Russian and pro-Russian forces along its eastern flank, and it has suffered through a war – a 20-month conflict between pro-Russian and pro-western forces in the early 1990s, which left up to 2,000 people dead.

Moldova, like other former Soviet republics and satellite states, has also long been a target of Russian influence operations and political manipulation, and some fear the fragile nation could unravel.

“This is a big risk,” Dan Perciun, a leading member of parliament, said in an interview. “And we have identified it from the very beginning.”

Last weekend, US secretary of state Antony Blinken visited Moldova in a show of support for its president, Maia Sandu, who was elected in 2020 in a surprise victory over the pro-Kremlin incumbent. She has asked to speed up European Union accession talks, though Moldova insists it will not join Nato for fear of undermining the delicate political balance in the country.

Leading officials of both the government and the opposition have held talks in an effort to cool political tempers. “What we have had here for a long time, since independence, was a society that was not always very united when it comes to foreign policy preferences and political orientation,” said Mr Popescu.

Moldova has a population of around 2.7 million, with roughly a fifth living in and around the capital, Chisinau.

With a population of around half a million, Transnistria is a bit larger than Suffolk and a bit smaller than the American state of Delaware. Some 1,300 Russian soldiers are garrisoned in the hilly territory, which, at 120 miles away from the frontier with EU and Nato member Romania, could be seen as the Kremlin’s westernmost outpost.

Run with an iron first by several former Soviet security officials, it is one of several Kremlin-backed nether states on the outer fringes of the former Soviet Union.

On Wednesday, during a surreptitious day-long visit to the enclave, The Independent spoke with residents about their fears. In the markets and cafes, there are hushed but passionate conversations about the war across the border in Ukraine. Roughly a third of Transnistrians are ethnically Russian, a third Ukrainian and a third Moldovan, with a smattering of others who settled here during the time of the Soviet Union and the chaotic years after its collapse.

“From a moral perspective, we are very troubled with what is happening in Ukraine,” said a woman in Tiraspol, walking through the central square in the capital of the Transnistrian enclave, where a gigantic statue of Vladimir Lenin stands among war monuments that include a Russian tank. “We’re worried. We are a multi-ethnic country. We love the fact that we have a lot of diversity here.”

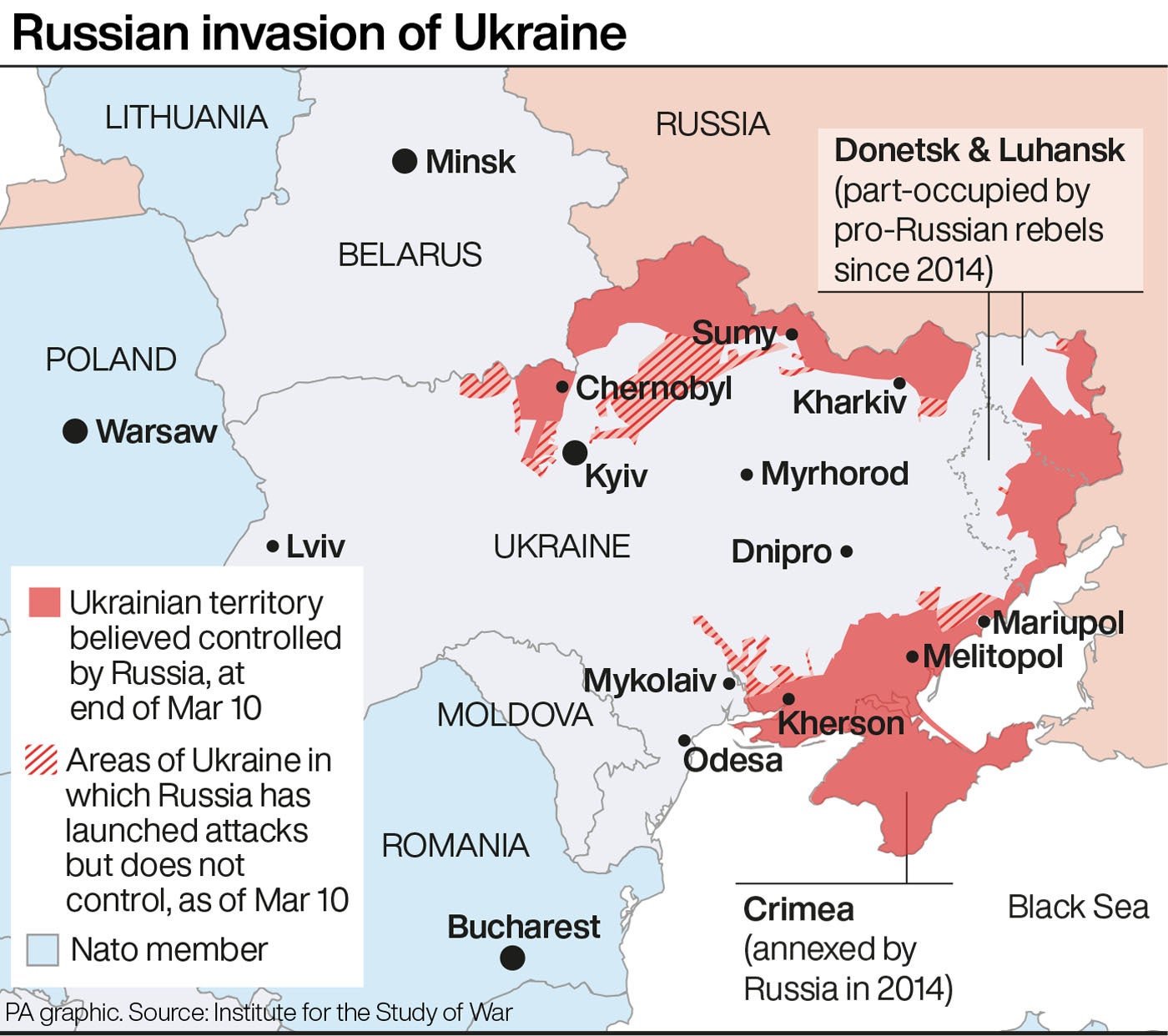

One woman in the covered marketplace in Bender said she has relatives in the Ukrainian city of Mykolaiv, the target of an ongoing Russian assault, and she has not heard from them since the war began.

“No matter how the war turns out, I am sure we here in Transnistria will pay a price,” she said.

Already the war has disrupted the flow of goods from Ukraine, as well as dividing families and friends. “I cannot judge; some people say it’s good and some say it’s bad, but I cannot judge who is right,” said Maria, a woman in her sixties selling hats and scarves at the Bender marketplace.

She added that her daughter lives near Ukraine’s embattled northeastern city of Kharkiv, and she is terrified for her.

A 19-year-old man, sitting among a group friends in an upscale cafe in Tiraspol, the administrative capital of the Transnistria enclave, praised the Russian forces for killing Ukrainian “Nazis”.

“I don’t choose a side,” said Mikhail, the 33-year-old manager of a restaurant in Bender. “In Transnistria, we live on both sides. This side is Moldova, this side is Ukraine. Over there is Russia. There are no problems.”

He said he refuses to watch the news any longer, or even check social media, because he is unable to sleep afterwards. “Every year I used to go to the sea at Odesa,” he said, referring to the Ukrainian Black Sea resort and port city now being menaced by Russian forces, less than two hours away. “I want everything to be like before.”

Moldovans, in general, appear more strongly supportive of the Ukrainian cause. After Ms Sandu’s narrow election victory in November 2020, her pro-EU party won 63 out of 101 parliamentary seats in elections in July 2021. A recent poll, conducted after the Russian invasion began, showed that 66 per cent of Moldovans support the country’s integration into the EU.

“I’m against the war; I’m not with Russia,” said Tatiana, a 46-year-old clerk at a bookshop in Chisinau. “I consider this war to be all Russia’s fault. We already had war in this country, and I remember it well. I am afraid Transnistria might again trigger a conflict.”

Unlike Ukraine – and Georgia, another former Soviet republic coveted by the Kremlin – Moldova’s constitution enshrines neutrality in the east-west conflict, and Moldovan officials have said repeatedly that the country will not seek Nato membership.

“We see no reason why Moldova would be drawn into the fighting,” said Mr Popescu. “We are a neutral country. We haven’t done anything that would justify an attack.”

Still, Alexander Lukashenko, the president of Belarus and a key Kremlin ally, included Transnistria on a battle map of Russian assets in eastern Europe, a gesture that sparked even more worry.

Moldovans also share a language and history with Romania, and at least 40 per cent hold a passport of another EU member state. Since the war in Ukraine, long queues of passport applicants have formed at the three Romanian diplomatic outposts in Moldova as fears of instability rise.

Moldovan officials say the country needs to prepare for a fresh array of threats emanating from the conflict next door. These include gun-running and criminality.

“When you have a war in proximity, it’s obvious the risks to public order and security are exponentially increased,” Ana Revenco, Moldova’s interior minister, said in an interview. “Having a war nearby where civilians are heavily armed increases the risk of cross-border trafficking of arms. There are luxury goods and cars left behind by people fleeing the war. That increases the risk of smuggling of goods.”

Moldova is also being targeted by social media campaigns in Romanian and Russian, suspected Kremlin-backed disinformation operations apparently aimed at destabilising the country by whipping up hostility towards refugees and the west.

“We have seen an orchestrated campaign on social media [presenting] Ukrainian refugees as thieves and unsavoury,” said Mr Perciun, the member of parliament. “There is clearly an attempt to inflame public opinion.”

Militarily, Moldova is weak, though Romania helped during the Transnistria war and could potentially back Chisinau in case of an attack. Artillery and air strikes may hit Moldova as the fighting inches closer to Odesa. On the other hand, Moldova’s mountainous terrain would make it difficult for any invading force coming from Transnistria.

“You don’t need a big military to try to cut them off and cut the entrances and approaches to Chisinau,” said Nuno Felix, a former Portuguese army special operations officer who has participated in Nato exercises in the Balkans. “The road to go through to the capital is mountains and valleys. I don’t think a move on Moldova would be something we would see easily. If Odesa falls, OK.”

But the most powerful hedge against an incursion into Moldova may be greed. Transnistria’s oligarchic rulers benefit from the largesse of Russia, Moldova and the EU, and they appear unwilling to risk their various enterprises, which have included smuggling of contraband, money laundering, and monopoly control over commerce, for the sake of what many in the post-Soviet world regard as Putin’s vain fantasy of uniting Russian-speaking lands under Moscow’s political authority.

Transnistria residents said that life had improved in recent years, and in the centre of Tiraspol lively new shops and cafes as well as luxury apartment complexes have flowered amid what even several years ago was a bleak landscape of decaying Soviet-era highrises and pock-marked roads.

“They are not ideologically motivated instruments of Russian expansion,” said Mr Perciun, referring to the oligarchs. “They are very content with the status quo and don’t share the broad narrative that Putin is putting forward. They don’t want to risk the status and wealth that they’ve attained. And I don’t see any underlying motivation for that to change.”

Calin Drugaliov contributed to this report